The Hydraulic Foundations of Ancient American Civilizations: Independent Development and Historical Parallels

The separate and independent rise of civilizations in the Old and New Worlds represents a profound natural experiment in human sociocultural evolution. Striking parallels emerged despite significant technological departures in the Americas, such as the absence of domesticated cattle, the wheel, and the plow. The independent emergence of pristine civilizations in regions requiring water management strongly supports the hydraulic hypothesis. This perspective holds that historical regularities fundamentally derive from the material and technical bases of human existence, a principle vividly demonstrated in the Americas.

Recent archaeological consensus confirms human presence in the Americas by at least 12,500 years ago. In Mesoamerica, the transition from Paleolithic hunter-gatherers to fully settled Neolithic villages was complete by 1500 BCE. By 1000 BCE, increasingly complex settlements occupied the humid lowlands. The Olmec culture, flourishing from 1150 to 600 BCE along Gulf of Mexico rivers, is often cited as the first American civilization. However, it functioned at a high Neolithic stage, comparable to European megalithic cultures, with towns under 1,000 people. Their achievements, including ceremonial centers, colossal Olmec stone heads, a calendar, and hieroglyphic writing, provided essential cultural models for successor civilizations despite their pre-urban scale.

The first true urban center in the New World was Monte Albán, founded around 500 BCE in the semi-arid Oaxaca Valley of Central Mexico. This planned city, likely formed from a confederation of regional powers, became the heart of Zapotec civilization. Engineers terraced a mountain to create an astronomically oriented acropolis with stone temples, pyramids, and a ball court. Supported by small-scale irrigation agriculture, the city housed 15,000 people by 200 BCE, expanding to 25,000 by 700 CE. The Zapotecs developed their own hieroglyphic script and a complex calendar before the city's eventual decline.

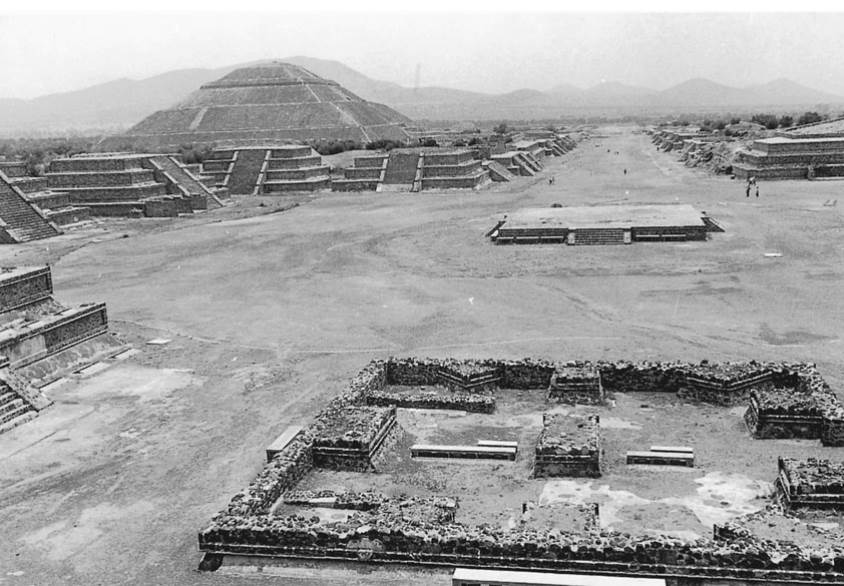

Coexisting with Monte Albán but vastly larger, the metropolis of Teotihuacan arose after 200 BCE in the dry Teotihuacan Valley. At its peak (300-700 CE), its population ranged from 125,000 to 200,000, making it the largest city in the Americas and a global urban powerhouse. The astronomically aligned city covered eight square miles, featuring the massive Temple of the Sun pyramid. Its existence was enabled by extensive hydraulic works and irrigation agriculture, including canals along the San Juan River. Control over the obsidian trade, extreme social stratification, and centralized royal/priestly authority cemented Teotihuacan's dominance over central Mexico.

Fig. 3.1. Teotihuacan. Cities and monumental building are defining features of all civilizations. Here, the huge Temple of the Sun dominates the ancient Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacan

Contemporaneously, Mayan civilization arose in the Yucatan wet lowlands, flourishing from 100 BCE to 900 CE. Initially, the Maya seemed to contradict the hydraulic model, but discoveries at sites like Pulltrouser Swamp revealed their sophisticated engineering. They practiced intensified wetland agriculture using raised fields interlaced with canals, which drained excess water and provided fertile sediment. This hydraulic system required collective management and produced surpluses sufficient for dense populations. The largest city, Tikal, housed 77,000 people and was characterized by monumental stepped pyramids, centralized kingship, and advanced astronomical systems.

In South America, the hydraulic pattern repeats emphatically. The arid Peruvian coast, crossed by short rivers from the Andes, formed an ecological analog to the Nile. Peruvian irrigation systems, collectively covering millions of acres, constitute the Western Hemisphere's largest archaeological artifact. Early villages emerged in over sixty valleys, with civilizations like the Moche (after 100 BCE) expanding via engineered canals. Their urban center, Pampa Grande, featured the Huaca del Sol pyramid. Similarly, the Chimu capital of Chan Chan was sustained by a vast hydraulic network.

In the southern highlands around Lake Titicaca, a potato-based agricultural system using raised fields fueled civilizations like Tiwanaku, which housed up to 120,000 people. The succeeding Inca Empire mastered water management and hydraulic engineering on an unprecedented scale. Their empire, spanning 2,700 miles at its 15th-century peak, was integrated by 19,000 miles of roads and featured monumental sites like Cuzco and Machu Picchu with exquisite terracing and water systems. The absolutist, state-controlled economy redistributed resources across diverse ecological zones.

Thus, the Urban Revolution in the Americas repeatedly depended on large-scale hydraulic engineering. While similarities with Old World civilizations are notable, they are best explained not by diffusion but by parallel adaptation to similar material and ecological constraints. The independent emergence of complex societies grounded in water control underscores fundamental regularities in the human journey from Neolithic roots to urban civilization.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;