The Origins of Science: Utilitarian Knowledge and Bureaucratic Institutions in Early Civilizations

A definitive characteristic of the world's earliest civilizations was the systematic development and institutionalization of higher learning, encompassing writing, literature, and the nascent forms of science. The independent emergence of arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and other primary societies indicates that these complex cultures produced a distinctive scientific tradition. This tradition was fundamentally shaped by the practical needs of the state and its religious apparatus, creating a form of knowledge profoundly different from later Greek pursuits. Consequently, in a sociological sense, practically oriented utilitarian science significantly preceded the abstract, theoretical investigations of classical antiquity.

In these first civilizations, knowledge was overwhelmingly subordinated to practical ends, providing essential services across society. It was deployed for record-keeping, political administration, economic transactions, and ensuring calendrical exactitude. Furthermore, it underpinned architectural and engineering projects, agricultural management, medicine, religious ritual, and astrological prediction. The state and temple authorities directly patronized the acquisition and application of this knowledge through cadres of learned scribes. Therefore, the early scientific endeavor was not a search for truth for its own sake, but a tool for maintaining social order, economic stability, and religious orthodoxy.

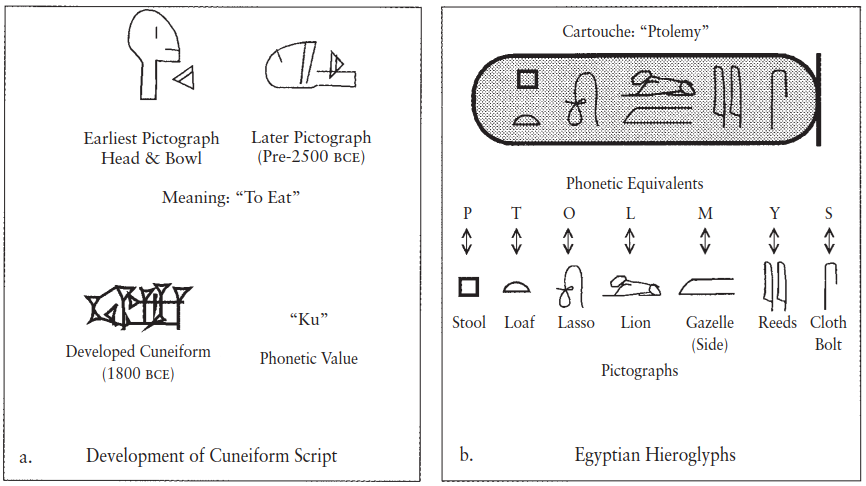

Fig. 3.5. a-b. Babylonian and Egyptian writing systems. Different civilizations developed different techniques for recording information in writing. Most began with representations called pictographs. Many later used signs to represent the sounds of a spoken language

The institutional homes for this knowledge were the bureaucratic structures of the palace and the temple. In Mesopotamian city-states, bureaucracies employed civil servants, court astrologers, and specialized calendar keepers. Similarly, in ancient Egypt, expert knowledge was centralized in the “House of Life” (Per-Ankh), a scriptorium and center of learning that maintained ritual knowledge while also harboring magical, medical, astronomical, and mathematical expertise. Archival halls and temple libraries served as repositories for this accumulated lore. These institutions employed hierarchies of court doctors, magicians, and learned priests, all operating within a framework of state patronage.

An additional hallmark of this bureaucratic pattern of science is the anonymity of its practitioners. The efforts of scribal experts were bent toward sustaining society rather than satisfying individual curiosity or achieving personal fame. Not a single biography of the individuals who contributed to science over centuries in these first civilizations has survived. Furthermore, knowledge was typically recorded in the form of lists—of omens, symptoms, or materials—rather than in analytical systems of theorems or generalized explanations. This reflects a characteristic lack of abstraction and a focus on the particulars of observable phenomena, devoid of overarching naturalistic theory.

The impetus for developing writing and reckoning systems was unequivocally practical. Centralized authorities managing large agricultural surpluses required reliable technologies for recording verbal and quantitative information. The archaeological record underscores these economic roots; for instance, 85% of the early cuneiform tablets from Uruk (c. 3000 BCE) are economic records. Similarly, the earliest Egyptian papyri detail administrative and commercial affairs. Writing began as a tool for inventory, contracts, and administration, only later evolving to encompass literary and religious texts. Ultimately, this technology supplanted oral traditions and revolutionized the capacity for information storage and transmission.

The scribal art was consequently highly valued, and its practitioners enjoyed elevated social status. Educated scribes formed a privileged caste patronized by the elite, and literacy offered a direct pathway to power and secure employment. The vast bureaucracies of these hydraulic civilizations provided careers for administrators and specialized posts for accountants, astronomer/astrologers, mathematicians, doctors, and engineers. It is no wonder that access to scribal training was typically restricted to the sons (and occasionally daughters) of the ruling and administrative classes, perpetuating a learned elite.

Formal education emerged with these civilizations, giving rise to the first schools. In Mesopotamia, scribal schools known as the e-dubba or “tablet house” taught writing, mathematics, and a standard curriculum of literature, including myths and proverbs. Student exercise tablets, found in abundance, reveal that these institutions could operate in the same location teaching an identical curriculum for a millennium. In Egypt, writing was taught in scribal schools attached to temples and palaces, which contained scriptoria and libraries. The countless surviving student exercises attest to the rigorous and standardized nature of this training, designed to produce uniform bureaucratic functionaries.

Although universal to early civilizations, writing systems varied considerably in form and evolution. The earliest system, cuneiform, arose with Sumerian civilization in Mesopotamia. Scribes used a wedge-shaped reed stylus to inscribe signs on clay tablets, which were then dried or baked for permanence. These tablets were stored in vast archives and libraries, with tens of thousands preserved to this day. The system began with hundreds of ideograms representing words or concepts but gradually incorporated phonographic elements to represent syllables of the spoken language. Interestingly, Akkadian, a Semitic language, later adopted cuneiform signs for their phonetic value to write its own tongue, while Sumerian was maintained as a scholarly, dead language.

In Egypt, pictographic writing appears from predynastic times, with formal hieroglyphs ("sacred carvings") established by the First Dynasty (c. 3000 BCE). While the idea of writing may have diffused from Mesopotamia, the Egyptian system developed independently. Hieroglyphs are primarily ideographic but early on incorporated phonetic components. With over 6,000 formal signs identified, scribes commonly used a core set of 700-800. For everyday administrative use, they developed simplified cursive scripts: hieratic and later demotic. The decipherment of this lost writing was made possible only by the Rosetta Stone, a trilingual stele deciphered by Jean-François Champollion in 1824.

A critical later development was the creation of the purely phonetic alphabet, where signs represent consonant and vowel sounds. This was an innovation of secondary civilizations, first appearing with the Phoenicians after 1100 BCE. The Greek and Roman alphabets are descendants of this revolutionary system, which greatly increased literacy's potential accessibility. However, in the first civilizations, the difficulty of mastering complex scripts like cuneiform and hieroglyphs ensured that literacy and the scientific knowledge it encoded remained the guarded domain of a professional scribal class, solidifying the link between knowledge, power, and the bureaucratic state.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;