The Hydraulic Hypothesis: Understanding the Independent Rise of Pristine Civilizations

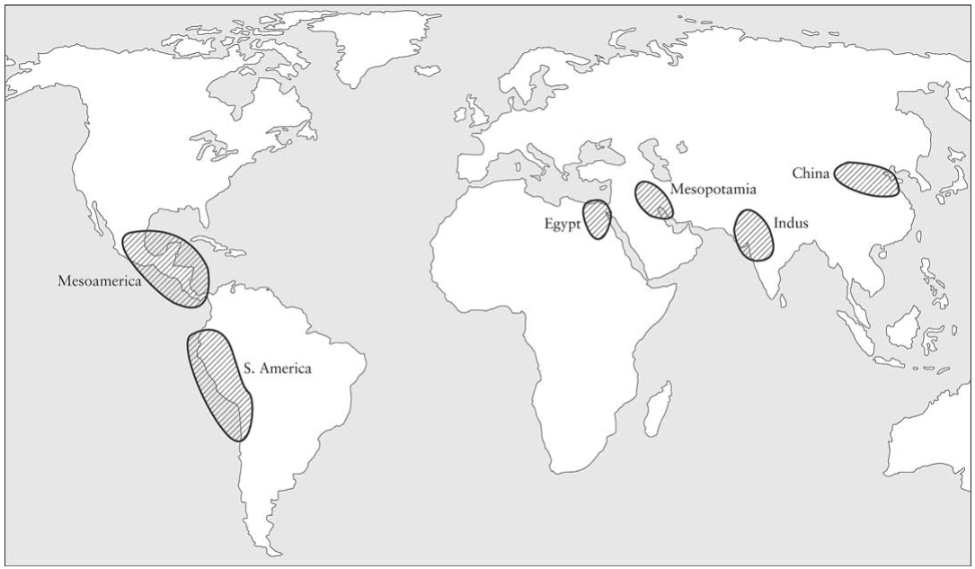

The Urban Revolution emerged independently in multiple centers across the Old and New Worlds. This remarkable pattern, where Neolithic settlements coalesced into centralized kingdoms based on intensified agriculture, occurred at least six times globally: in Mesopotamia after 3500 BCE, Egypt after 3400 BCE, the Indus River Valley after 2500 BCE, China after 1800 BCE, Mesoamerica around 500 BCE, and South America after 300 BCE. These pristine civilizations developed essentially independently, not through diffusion from a single center, prompting inquiry into the common causal factors behind their parallel emergence.

A key explanation for this repeated phenomenon is the hydraulic hypothesis, which links state formation to large-scale water management. Scholars emphasize that these civilizations arose in hydrologically distressed regions, where water scarcity or flooding necessitated major engineering. The construction and maintenance of hydraulic engineering works—such as dams, dikes, canals, and irrigation systems—required coordinated communal effort and authoritative control over labor and resource distribution, reinforcing trends toward a centralized, authoritarian state.

Map 3.1. The earliest civilizations. The transition from Neolithic horticulture to intensified agriculture occurred independently in several regions of the Old and New Worlds. Increasing population in ecologically confined habitats apparently led to new technologies to increase food production.

The concept of “environmental circumscription” further elucidates this process. Civilizations developed in geographically restricted zones, like river valleys surrounded by deserts or mountains, where intensive farming was only possible within finite lands. As Neolithic populations expanded, they pressed against these ecological limits, leading to conflict, conquest, and the subjugation of defeated groups who could no longer migrate. This dynamic created a stratified society with a dominant elite controlling an agricultural underclass, setting the stage for state formation.

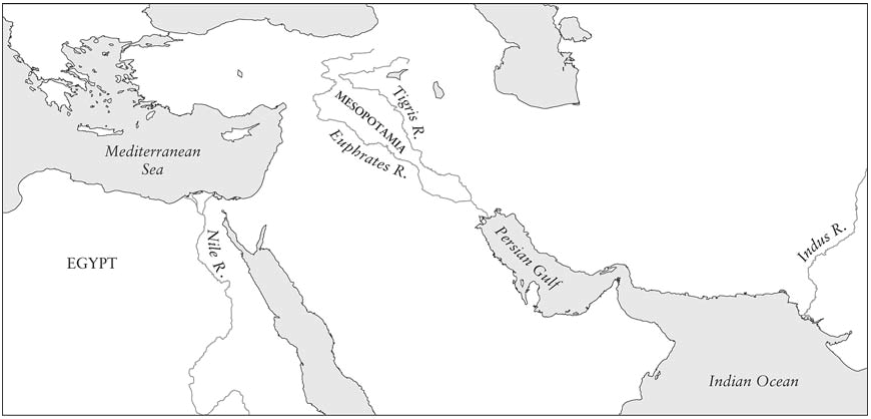

This model aptly describes the first human civilization in ancient Mesopotamia, the land “between the rivers.” By 4000 BCE, villages filled the plain; authorities drained marshes and built extensive irrigation works. Following 3500 BCE, great walled city-states like Uruk, Ur, and Sumer arose, with the Sumerian civilization fully formed by 2500 BCE. Despite the shifting courses of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers preventing a single unified kingdom, successive empires like Babylon and Assyria emerged, each absorbing and adapting the cultural and technological foundations of their predecessors.

Map 3.2. Hydraulic civilizations. The first civilizations formed in ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) on the flood plain of the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers, astride the Nile River in Egypt, and along the Indus River. The agricultural benefits of annual flooding were intensified by hydraulic management.

All Mesopotamian civilizations were fundamentally based on irrigation agriculture, supported by massive canals and complex bureaucracies to manage surplus. They are characterized by monumental building, most notably the ziggurats, which were great brick temple pyramids. For example, Ur-Nammu’s ziggurat at Ur (c. 2000 BCE) was part of a vast complex, and Nebuchadnezzar’s tower (600 BCE) reportedly inspired the biblical Tower of Babel. This civilization also pioneered writing, mathematics, and sophisticated astronomy.

Ancient Egypt followed a similar trajectory, constrained within the narrow, fertile ribbon of the Nile River Valley. After Neolithic kingdoms emerged, tradition holds that King Menes, first pharaoh of the first dynasty, united Upper and Lower Egypt and initiated hydraulic projects by embanking the Nile at Thebes. Managing the Nile's annual floods enabled an explosive growth of civilization, marked by early monumental building like the pyramids at Giza, a massive army, absolute pharaonic authority, and the development of bureaucracy, writing, and astronomy.

While less is known of the Indus River Valley Civilization (or Harappan civilization), its outlines are clear. By 2300 BCE, the planned cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa featured protective embankments, grid streets, towers, granaries, and advanced sewer systems. At Mohenjo-daro's center stood a citadel containing the Great Bath, a large manmade pool. This urban planning indicates strong central authority, likely priestly-bureaucratic in nature. The civilization declined after 1750 BCE, possibly due to climatic shifts and changes in the Indus River's course.

In China, the pattern repeated along the Yellow River (Hwang-Ho). Legendary ruler Yu the Great of the Hsia dynasty is famed for controlling floods. The documented Shang (Yin) dynasty (1520-1030 BCE) mastered the plain through extensive irrigation, a role of government that continued throughout Chinese history. This led to widespread dikes, dams, and canals, like the massive Lake Quebei, built via corvée labor extracted from peasants.

Early Chinese civilization was highly stratified, with emperors as high priests and elaborate royal burials. Following unification in 221 BCE, unprecedented authority was centralized in the emperor, supported by a formidable bureaucracy. Monumental projects defined the era, including the initial 1,250-mile construction of the Great Wall of China and the later 1,100-mile Grand Canal. Writing, mathematics, and astronomy flourished, completing the suite of complex institutions characteristic of a pristine civilization.

The recurrent rise of these civilizations in disparate regions underscores significant regularities in history, contradicting the view of history as merely a sequence of unique events. While future research will add nuance, the common pattern—where environmental circumscription, hydraulic engineering, and intensified agriculture catalyzed social stratification and state formation—provides a powerful explanatory framework for the independent origins of early civilizations worldwide.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;