Hydraulic Civilizations of Ancient Sri Lanka and the Khmer Empire: Science, Irrigation, and Monumental Building

The intrinsic correlations between scientific development and hydraulic civilization are profoundly evident in the case of Buddhist Sri Lanka, historically known as Ceylon. Following invasions from the Indian mainland in the sixth century BCE, a quintessential hydraulic civilization emerged, founded by legendary “water kings” and sustained by a distinctive Sinhalese civilization for over 1,500 years. This society mastered the collection of irregular rainfall through thousands of tanks and catchments, enabling the spread of irrigation agriculture and grain production in the island’s northern dry zone. The definitive hallmarks of such a civilization appeared, including centralized authority, a governmental irrigation department, corvee labor, agricultural surpluses, and monumental construction. This building program involved shrines, temples, and palaces built with tens of millions of cubic feet of brickwork on a scale rivaling the Egyptian pyramids, which in turn supported large urban population concentrations. Indeed, the primary city of Polonnaruwa was reportedly the world's most populous city during the twelfth century CE.

While historical details remain somewhat fragmentary, records indicate strong royal patronage of expert knowledge in ancient Sri Lanka, supporting work in astronomy, astrology, arithmetic, medicine, alchemy, geology, and acoustics. A bureaucratic caste, seemingly centered on temple scholars, also existed, with the chief royal physician holding a major governmental position. Following a pattern established in India by Emperor Asoka, the state allocated considerable resources to public health and medical institutions, including hospitals, lying-in homes, dispensaries, kitchens, and medicine-halls. Collectively, Sri Lanka exemplifies a classic pattern of state-patronized, useful science within a hydraulic societal framework.

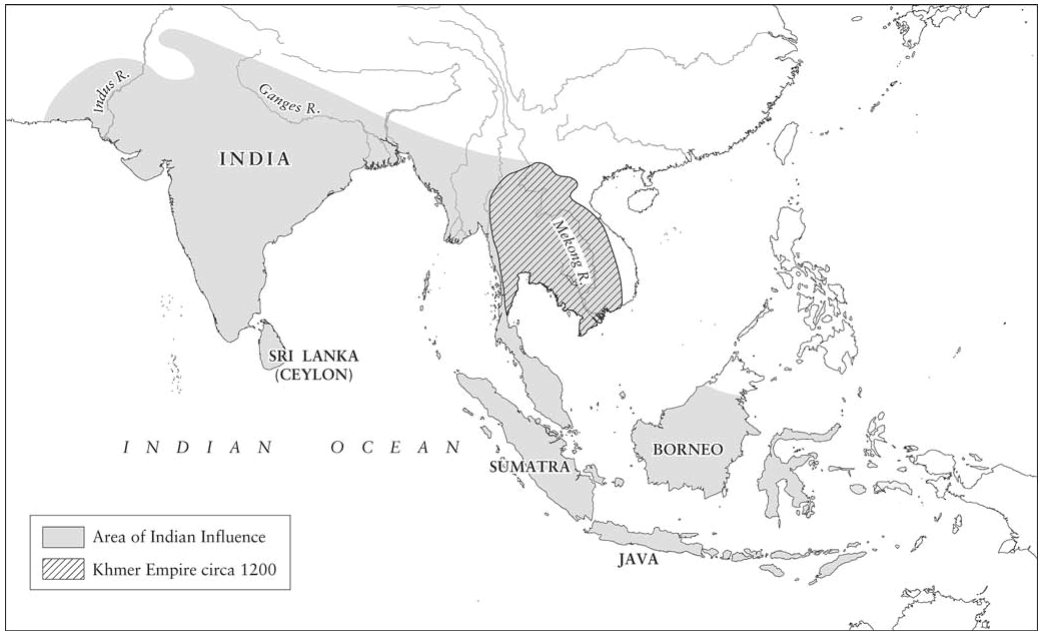

Map 8.2. Greater India. An Indian-derived civilization arose on the island of Sri Lanka (Ceylon), and Indian-inspired cultures also developed in Southeast Asia, notably in the great Khmer Empire that appeared in the ninth century CE along the Mekong River.

From an early period in the first millennium CE, Indian merchants voyaged eastward across the Indian Ocean. Through extensive trade contacts and sea links to Sumatra, Java, and Bali in Indonesia, coupled with cultural exchange with Buddhist missionaries from Sri Lanka, a pan-Indian civilization arose in Malaysia and Southeast Asia. A third-century account by a Chinese traveler, for instance, reported an Indian-based script, libraries, and archives in the Funan kingdom in modern Vietnam. Indian influence expanded significantly during the fourth and fifth centuries, as Brahmins from India were welcomed by local rulers, bringing Indian law and administrative procedures. Sanskrit became the language of government and learned religious commentary, while Hinduism and Buddhism coexisted as dominant faiths.

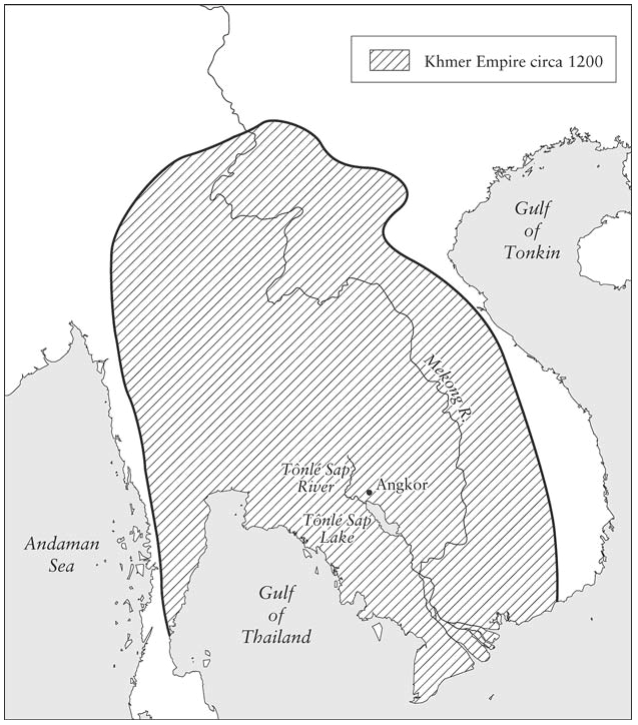

The most remarkable example of this cultural diffusion is the great Cambodian or Khmer Empire. A prosperous and independent kingdom for over six centuries from 802 to 1431 CE, it reached its zenith under King Jayavarman VII (r. 1181-1215 CE), becoming the largest political entity in Southeast Asian history, encompassing parts of modern Cambodia, Thailand, Laos, Burma, Vietnam, and the Malay Peninsula. The empire’s foundation was the alluvial plains of the lower Mekong River, and its immense wealth derived from the most substantial irrigation infrastructure in regional history. Exploiting the annual monsoon floods, Khmer engineers constructed an enormous system of artificial lakes, canals, channels, and shallow reservoirs with long embankments known as barays to control water and ensure its distribution during the dry season. By 1150 CE, this system artificially irrigated over 400,000 acres, with the East Baray at Angkor Wat alone measuring 3.75 by 1.25 miles. This hydraulic mastery supported intensive rice cultivation, which fueled dense populations, a vast labor force, and a wealthy elite.

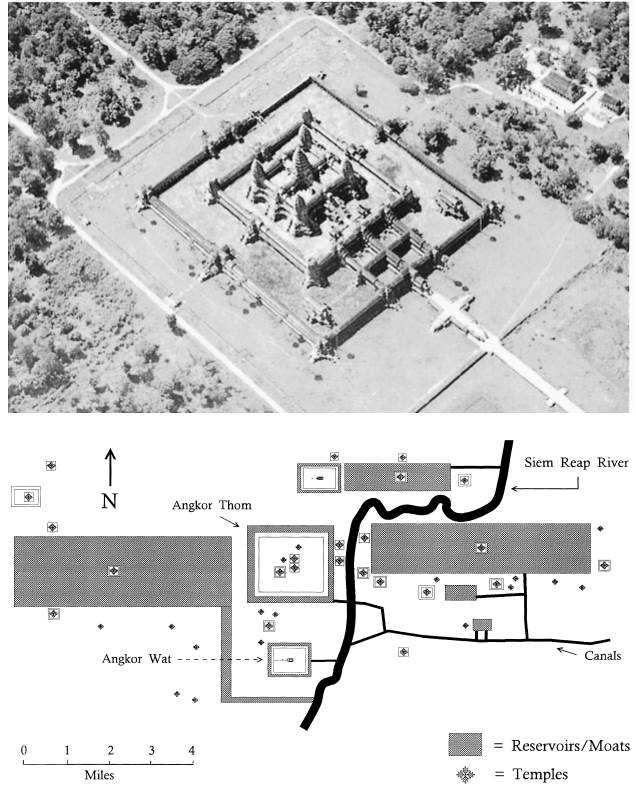

The social and scientific patterns typical of hydraulic civilization were replicated in the Khmer Empire. Khmer kings, considered living deities akin to Egyptian pharaohs, exercised potent centralized authority. A complex bureaucracy, led by an oligarchy of learned Brahmins and military officers, managed daily imperial affairs—a structure some sources label an early welfare state, partly due to Jayavarman VII’s reported construction of 100 public hospitals. The bureaucratic state maintained various libraries and archives, indicative of higher learning. Beyond irrigation and an extensive highway system, Khmer royal power directed prodigious construction, most notably in the capital district of Angkor, developed over 300 years. This urban center covered 60 square miles and comprised a series of towns along coordinated axes. Among approximately 200 temples, each with its own practical and symbolic reservoirs and canals, the Angkor Wat complex is the world's largest religious monument.

Map 8.3. The Khmer Empire. Based on rice production and the hydrologic resources of the Mekong River and related tributaries, this Indian-inspired empire flourished magnificently in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Based on substantial irrigation and impounded water technologies, the Khmer Empire constituted the largest political entity in Southeast Asian history.

It exemplified the typical trappings of high civilization, including monumental architecture, literacy, numeracy, astronomical knowledge, and state support for useful science. The empire ultimately declined with the demise of its irrigation infrastructure in the early fifteenth century. The Khmer court actively patronized science and useful knowledge, attracting Indian scholars and with them Indian astronomy and alchemy. A distinct caste of teachers and priests taught Sanskrit texts and trained astrologers and court ceremonialists. The reported Khmer hospitals suggest organized medical training and practice. The unity of astronomy, calendrical reckoning, astrology, numerology, and architecture is manifest in Angkor Wat’s design, meticulously aligned according to Indian cosmology as a symbolic sacred mountain. Its thousands of bas-relief carvings indicate interests in elixirs of immortality, and the complex incorporates astronomical sight lines for tracking solar and lunar motion, with special emphasis on the spring equinox. These embedded sight lines enabled eclipse prediction, though whether Khmer astronomers utilized this capability remains speculative.

Fig. 8.1. Angkor Wat. Among the 200 temples in the region, each with its own system of reservoirs and canals, Angkor Wat is the largest temple complex in the world. Surrounded by a moat almost 660 feet wide, the temple is made of as much stone as the great pyramid at Giza, and virtually every square inch of surface area is carved in bas-relief. The complex was completed in 1150 CE, after fewer than 40 years of construction.

Overbuilding and ecological strain may have exhausted the Khmer state, sapping its vitality. From the fourteenth century, the empire faced repeated invasions from Thai and Cham (Vietnamese) peoples. These attacks critically damaged the essential irrigation infrastructure: maintenance halted, wars caused destruction, and military conscription drained the corvee labor force. Consequently, populations collapsed, leading to the empire’s fall. The Thais conquered, Sanskrit faded as the scholarly language, a less ornate Buddhist style prevailed, and Angkor was abandoned to the jungle by 1444. French explorers “rediscovered” the ruins in 1861. Though lost for centuries, Khmer civilization powerfully demonstrates the recurring pattern of agricultural intensification, bureaucratic centralization, and the patronage of useful sciences inherent to hydraulic civilizations.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;