Science and Technology of the Inca Empire: Astronomy, Engineering, and Quipu Record-Keeping in Pre-Columbian South America

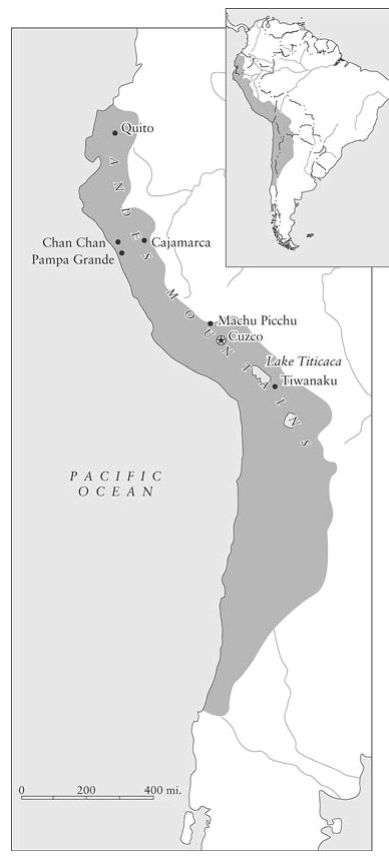

The Inca Empire (Tawantinsuyu) represents a classic example of independent civilizational development, paralleling patterns observed in other pristine civilizations globally. Flourishing between the 13th and 15th centuries CE, this pre-Columbian state extended over 2,000 miles along South America's western coast, between the Andes Mountains and the Pacific Ocean. Its foundation was a sophisticated hydraulic and agricultural system, featuring monumental terracing and irrigation that supported a highly stratified, bureaucratized society. This engineered landscape enabled the concentration of resources and power essential for state formation and scientific development.

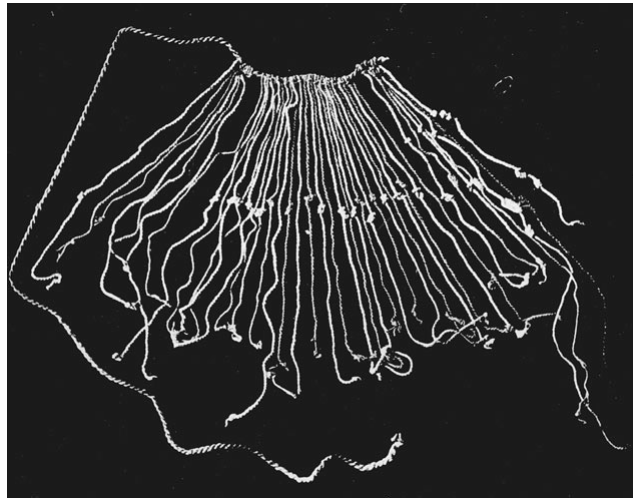

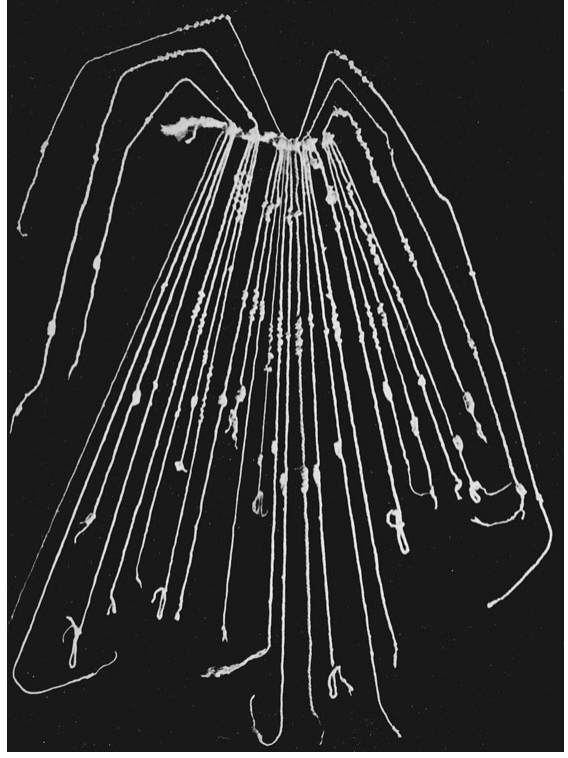

Contrary to possessing writing systems or formal mathematical notation, the Inca developed the ingenious quipu (or khipu), a complex device for recording information using knotted strings. This system was integral to the imperial administration, documenting tax obligations, census data, and historical narratives. The empire was organized on a strict decimal system, with units managing from 10 to 10,000 individuals, and employed standardized weights and measures. A hereditary class of accountants memorized and interpreted the data encoded in these quipu, ensuring the state's economic and demographic control.

Inca astronomy was a deeply integrated state science. Astronomer-priests mapped the heavens by dividing them into quarters, guided by the seasonal shifting of the Milky Way in the Southern Hemisphere. They utilized natural Andean horizons and constructed artificial stone pillars to track solstices and the motions of celestial bodies. From the central Coricancha temple in Cuzco, 41 sight lines, or ceques, radiated outward, functioning as a colossal cosmographic map. These lines marked lunar positions, water sources, and political boundaries, effectively transforming the capital into an architectural quipu and calendar.

The Inca maintained dual calendar systems to regulate state and ritual life. A 365-day solar calendar consisted of twelve 30-day months, supplemented by five festival days and reset at the December solstice. They also tracked a lunar calendar of 328 days, organized into 41 eight-day weeks. Observations of the heliacal rising of the Pleiades constellation were critical for synchronizing these calendars and timing agricultural and labor cycles, such as the deployment of corvée labor coinciding with seasonal rains. This celestial regulation underscored the theocratic state's synchronization of cosmic and social order.

Inca engineering prowess extended beyond agriculture to include monumental architecture and road systems. Sites like Machu Picchu were constructed with precise astronomical orientations, such as the Intihuatana stone serving as a solstice indicator. This integration of science, urban planning, and sacred geography demonstrates a holistic worldview where technology served ideological and administrative imperatives. The empire's infrastructure facilitated control and communication across its vast, mountainous territory.

Medical and botanical knowledge was remarkably advanced, with state-appointed herbalists and specialized doctors. Inca surgeons skillfully performed amputations and trepanation—the surgical drilling of holes in the skull, likely to relieve cranial pressure from battle injuries or disease. Furthermore, they mastered mummification techniques, preserving the bodies of elites for ritual purposes and reinforcing the cultural link between ancestors, cosmology, and political authority. This empirical knowledge was accumulated and transmitted through expert apprenticeships.

The empire's trajectory was catastrophically interrupted in 1532 with the arrival of Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro. The collapse of Inca civilization, following the fall of the Aztec Empire a decade prior, irrevocably redirected the scientific and technological history of the Americas, subsuming indigenous knowledge systems under European paradigms. Consequently, understanding Inca achievements relies heavily on archaeological evidence and post-conquest chronicles, which continue to reveal the sophistication of this late-flowering Andean civilization.

Map 9.2. The Inca empire. On the west coast of South America the Inca built on cultural developments of the previous 1,000 years and created a high civilization between the Andes Mountains and the Pacific Ocean where engineers terraced mountains and built irrigation systems tapping numerous short rivers to intensify agriculture.

Fig. 9.6. Inca recordkeeping. All high civilizations developed systems of record-keeping, usually in the form of writing. The Inca used knotted strings called quipu for recording numerical and literary information.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;