Deciphering Mayan Civilization: Writing, Astronomy, and Mathematical Systems

Our understanding of Mesoamerican "glyph" writing remains fragmentary due to the systematic destruction of indigenous records by Spanish conquerors. They obliterated thousands of codices—fanfold books made of bark paper or deerskin—leaving only four surviving Mayan examples. Consequently, the primary corpus consists of approximately 5,000 texts engraved on stone stelae and architectural elements, some containing hundreds of carved signs. Significant advances in deciphering ancient Mayan now allow for accelerated translation, with roughly 85 percent of known glyphs decoded. This writing system, with Olmec roots, is now known to be a fully functional script combining phonetic and logographic components to represent the distinct Mayan language.

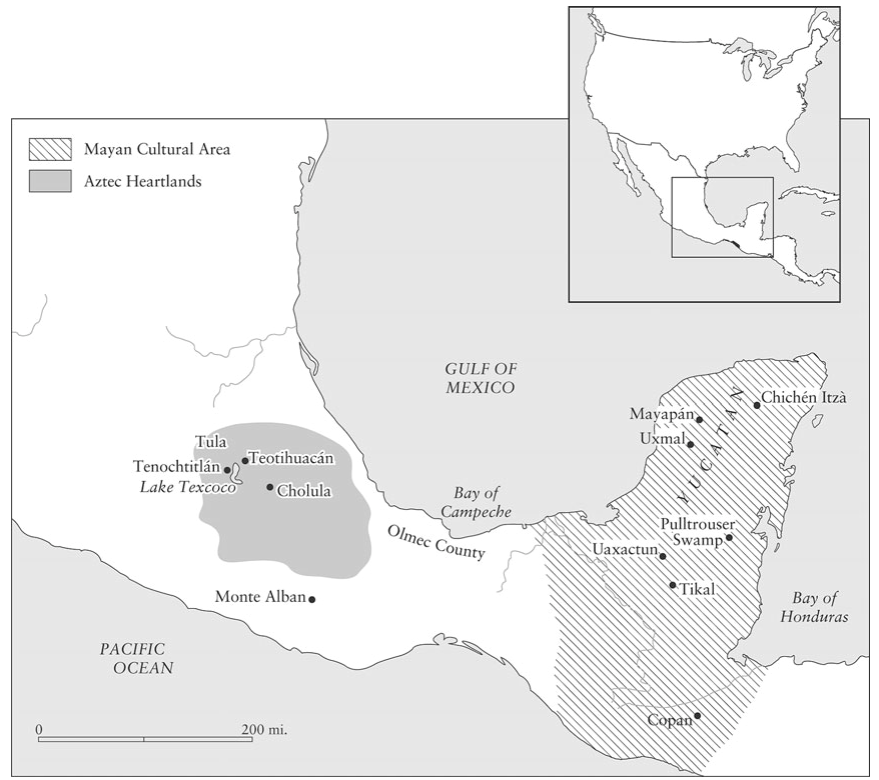

Map 9.1. Civilization in Mesoamerica. High civilization arose independently in Central America. Mayan civilization centered itself in the humid lowlands surrounding the Bay of Honduras, and, later, the Aztec empire arose in a more desert-like setting around a lake where modern Mexico City stands.

Of the 287 deciphered hieroglyphic signs, 140 carry phonetic value, revealing that these public inscriptions primarily recorded historical and ritual events. The content focuses on the reigns, military exploits, and dynastic lineages of Mayan kings and ruling families. This medium naturally overrepresents dynastic propaganda and elite agendas. Had the vast written records on perishable materials survived, a more balanced and mundane picture of Mayan society would undoubtedly emerge. The inherent complexity of the script implies it was mastered by a specialized, highly trained caste.

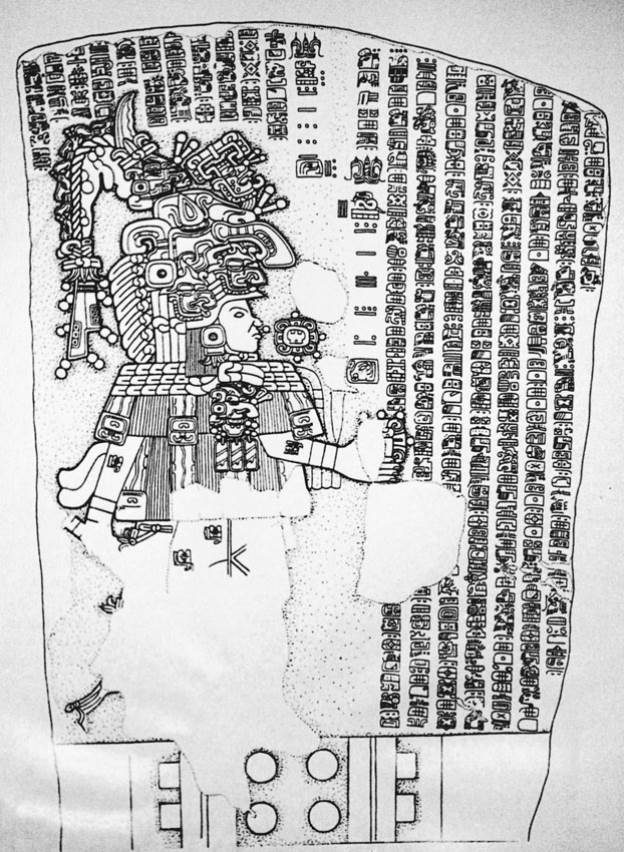

Fig. 9.1. Pre-Mayan stela. The complex writing system used in Mayan civilization has now been largely deciphered. Based on earlier antecedents like the second-century CE stone carving shown here, the Mayan form of writing used glyphs that possessed phonetic or sound values. Mayan inscriptions had a public character, commonly memorializing political ascendancy, warfare, and important anniversaries.

The Mayan scribes formed an exclusive, high-status profession within a highly stratified society. Recruited from the noble class, often as the younger sons of kings, their positions were likely hereditary. Scribes functioned as high courtiers, royal confidants, and sometimes political aspirants. Centers like Mayapan housed separate academies for training priests and scribes, who worshipped Itzamna, the creator god and patron of writing and learning. The caste was marked by distinctive headdresses, special utensils, and were often buried with codices in lavish ceremonies, solidifying their role as the Mayan intellectual class.

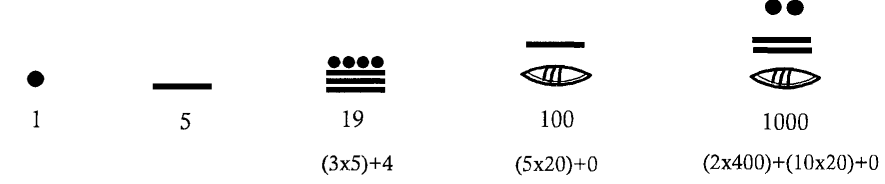

For computation, the Maya employed a sophisticated vigesimal, or base-20, system. This system utilized a dot for one and a bar for five, a choice possibly correlating with human digits. Crucially, they developed a place-value system complete with a symbol for zero, enabling calculations of extraordinarily large numbers. While they did not use fractions, Mayan mathematicians created tables of multiples to aid computation, similar to earlier Babylonian practices. This mathematical expertise was primarily applied to ritual astronomy, numerology, and their elaborate calendrical systems.

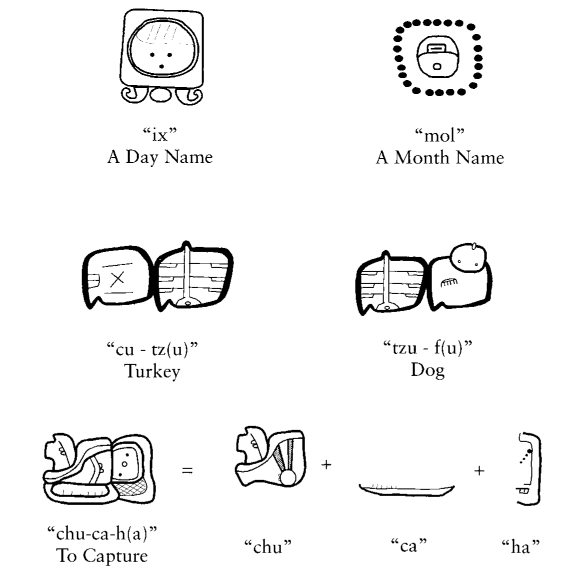

Fig. 9.2. Mayan word signs. The originally pictographic character of pre-Mayan and Mayan languages came to assume phonetic values. These signs could be combined to represent other words and concepts.

Fig. 9.3. The Mayan vigesimal number system. The Mayan number system was a base-20 place-value system with separate signs for 0, 1, and 5. Note that the “places” are stacked on top of one another.

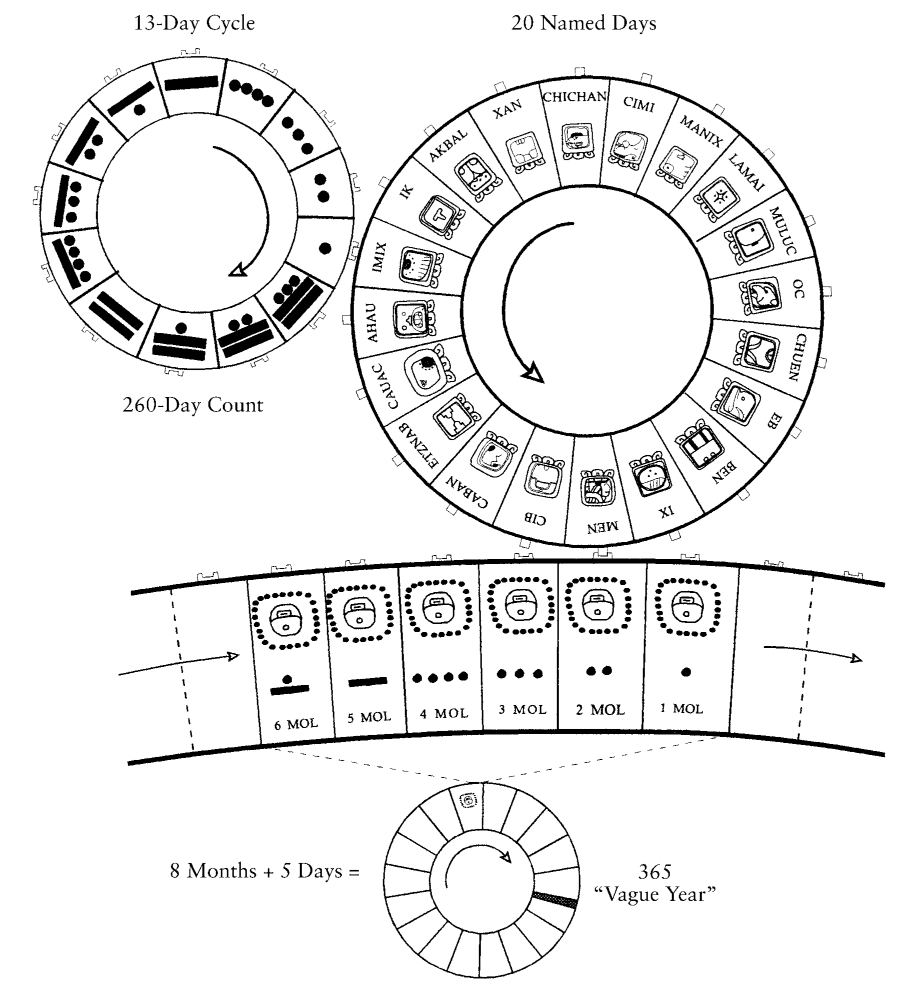

The Mayan calendar is among the most complex ever devised, integrating multiple simultaneous cycles. The sacred tzolkin was a 260-day cycle, generated by the interplay of 13 numbers and 20 day-names, possibly related to human gestation. They also used a 365-day "Vague Year" (haab'), comprising eighteen 20-day months plus a short, unlucky period of five days. Meshing these created the Calendar Round, a 52-year cycle where every day had a unique designation used for astrological divination and prophecy.

Fig. 9.4. Mayan Calendar Round. Like their counterparts in all other civilizations, Mayan astronomers developed a complex and reliable calendar. Theirs involved elaborate cycles of days, months, and years. It took 52 years for the Mayan Calendar Round to repeat itself.

For linear historical record, the Maya used the Long Count, a sequential tally of days in units from a single day (kin) up to the b'ak'tun (roughly 394 years). The epoch, or start date, of the current Long Count cycle corresponds to August 13, 3114 BCE in the Gregorian calendar. Mayan astronomers also maintained a precise lunar calendar and conceived of vast mythological time spans. This intricate time-reckoning was deeply intertwined with Mayan astronomy, a sacred science dedicated to observing celestial cycles for ritual and political purposes.

Astronomical observations were conducted from specialized structures like the Caracol at Chichen Itza, an edifice functioning as an observatory. Its windows and alignments marked the extremes of Venus's risings and settings, equinoxes, solstices, and other celestial events. Similar architectural orientations are found at Copan, Uaxactun, and Uxmal, indicating that city planning often mirrored the cosmos, particularly the path of Venus and the sun's zenith passages, which were critical for agricultural scheduling.

Fig. 9.5. The Mayan "observatory" at Chichen Itza. From the observing platform of the Caracol ancient Mayan astronomers had a clear line of sight above the treetops. The various windows in the structure align with the risings and the settings of Venus and other heavenly bodies along the horizon.

Surviving codices reveal a highly sophisticated astronomical science. Mayan astronomers calculated the solar year to high accuracy and determined the lunar month as 29.530 days, a figure precise to three decimal places. They created accurate eclipse prediction tables and devoted particular attention to Venus, maintaining a separate Venus calendar and refining its synodic period to within two hours error over 481 years. They harmonized cycles of Venus, the sun, and the tzolkin into grander interlocking periods, and likely tracked Mars and Mercury as well.

This esoteric knowledge had profound utilitarian and political applications. Calendrical mastery informed agricultural cycles and governed ritual activities. Astrological divination determined propitious times for all endeavors, including warfare, as evidenced by the timing of military campaigns to Venus's phases. Thus, Mayan astronomy and writing were integral to the ideological underpinnings of royal power and social order.

The collapse of classic Mayan civilization around 900 CE in the central lowlands remains a topic of debate, likely caused by a confluence of factors. Endemic warfare, population pressure on a fragile ecosystem, and severe deforestation for lime-plaster production degraded the environment. This was compounded by a severe, multi-century drought that crippled agriculture. Although a post-classic resurgence occurred at centers like Chichen Itza, the Long Count and the rigorous scribal tradition declined. The complex system of knowledge the Maya developed gradually waned, leaving its rich legacy to be rediscovered through modern archaeological and epigraphic decipherment.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;