The History of Science and Technology in Ancient and Classical India: Achievements and Influences

Urban civilization on the Indian subcontinent flourished for over 1,500 years prior to the rise of universities in Europe, fostering advanced professional work in mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. Recent scholarly interest, inspired by studies of Chinese science, has yet to produce a matching comprehensive synthesis for India. While historians have analyzed texts, often highlighting pioneering "firsts," deeper research is still required to fully understand the Indian context. This civilization exhibited classic bureaucratic hallmarks: irrigation agriculture, political centralization, social stratification, and utility-focused higher learning.

Compared to China or the Islamic world, traditions in the natural sciences were less vigorous in India, partly due to the transcendental nature of its major religions. Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism often viewed the everyday world as an illusion, emphasizing escape from karma over understanding nature's laws. These spiritually rich philosophies did not encourage the study of underlying natural regularities. Consequently, the pursuit of knowledge was directed toward metaphysical truth rather than empirical investigation of the physical world.

Civilization emerged in the Indus River Valley during the third millennium BCE but declined after 1800 BCE, likely due to ecological shifts. The subsequent society comprised decentralized agricultural communities, tribally organized under kings and priests. Settlement spread to the Ganges basin, and early society was divided into four orders: priests (Brahmins), warriors, peasants/tradesmen, and servants, forming the basis of the caste system. The Brahmin class monopolized education, ritual expertise, and statecraft, guarding sacred lore considered essential for cosmic order.

Historical understanding of India before the sixth century BCE relies on literary evidence from religious texts, the Vedas (1500-1000 BCE), and later Brahmanic commentaries. These originally oral works were codified with the advent of writing, revealing scientific knowledge aimed at maintaining social and cosmic structures. Given the sacred power of oral recitation, linguistics and grammatical studies became India's first sciences. The Sanskrit grammar of Panini (5th century BCE), with 3,873 rules, exemplifies this, while the need for precise recitation spurred studies in acoustics and musical tones.

A subsidiary group of Vedic and Brahmanic texts dealt with astronomy and mathematics, indicating a professional class of priests and astrologers. Experts developed calendars to regulate rituals, creating solutions for synchronizing lunar and solar cycles, including the system of lunar mansions (nakshatras). Mathematics was essential for altar construction and orientation. Early mathematicians also engaged with very large numbers, naming values up to 10^140, reflecting Hindu and Buddhist concepts of vast cosmic cycles.

The Indian subcontinent was notably open to outside influences, affecting its scientific traditions. The Persian invasion in the sixth century BCE introduced Babylonian astronomy, while Alexander the Great's incursion in 327-326 BCE facilitated the diffusion of Greek science. Conversely, Indian achievements later influenced the Islamic world, China, and Europe. This exchange highlights India's role in a broader Eurasian network of knowledge.

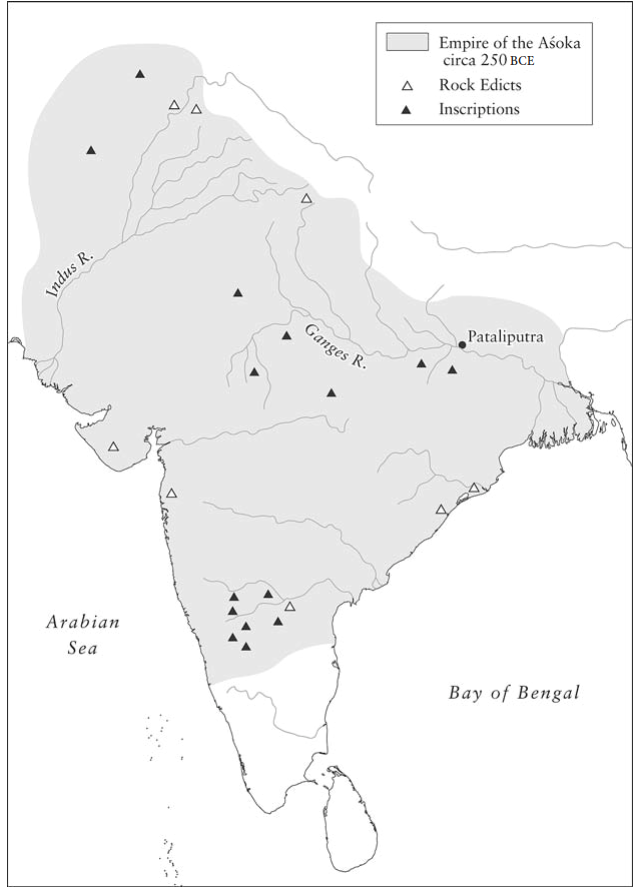

Political unification began with the Mauryan empire, founded by Chandragupta Maurya (r. 321–297 BCE) and expanded by his grandson Ashoka (r. 272–232 BCE). The empire was a quintessential hydraulic civilization, with state-managed irrigation supporting double harvests and providing key revenue. A Greek traveler, Megasthenes, reported extensive canals and sluices. Water was state property, and damaging irrigation infrastructure was a capital offense, underscoring its critical importance.

The Mauryan empire featured a complex bureaucracy with superintendents overseeing commerce, mining, and state industries. It maintained a large standing army and an extensive network of spies. The capital, Pataliputra, was a fortified city with monumental architecture, including a grand wooden palace. Public works included tree-lined roads, rest houses, and a mail service, reflecting advanced urban planning and administration.

Expert knowledge continued under the Mauryans. Brahmin scholars retained influence, and cities became centers of learning. Officials like the superintendent of agriculture used rain gauges and compiled meteorological data. Ashoka established infirmaries for humans and animals. Furthermore, Babylonian and Hellenistic influences, such as the twelve-sign zodiac, became integrated into Indian astrology, linking science with patronage and practical utility.

Following Ashoka’s death, India fragmented until reunification under the Gupta dynasty in the fourth century CE, marking a golden age of classical Indian civilization. The Gupta period saw flourishing scholarship in astronomy, mathematics, medicine, and linguistics, supported by royal patronage. Like its predecessor, the Gupta state relied on strong central power, public works, and land revenue, creating an environment conducive to scientific advancement.

Indian astronomy under the Guptas remained practical and astrologically focused, dedicated to calendar-making, horoscopes, and determining auspicious times. It was highly mathematical but not strongly observational or theoretical. Astronomers operated in isolated, conservative family traditions, with six competing regional schools. Despite this, they produced sophisticated textbooks (siddhantas) covering planetary theory, eclipses, and the precession of the equinoxes.

Notable astronomers emerged during this era. Aryabhata I (b. 476 CE) proposed Earth’s rotation, a view contested by later scholars like Brahmagupta (b. 598 CE), who provided an accurate estimate of Earth’s circumference. Their work was deeply mathematical, employing a place-value decimal system with zero—a concept possibly rooted in Indian philosophical notions of nothingness. Aryabhata calculated π to four decimals, later extended to nine, while Brahmagupta advanced algebra, trigonometry, and the concept of negative numbers.

The field of medicine, Ayurveda or the "science of life," became highly institutionalized. The Charaka Samhita (c. 1st century CE) and Susruta Samhita outlined sophisticated medical theory, surgery, and extensive anatomical classification. Major centers of learning like Nalanda University (5th–12th centuries CE) taught thousands of students. Court physicians held high status, and veterinary medicine for war elephants and horses was also advanced, reflecting a comprehensive and rational medical tradition.

Alchemy, closely tied to medicine and Tantric Buddhism, developed sophisticated chemical knowledge focused on mercury, elixirs, and longevity. Technologically, pre-colonial India was an "industrial society," leading the world in textile production and shipbuilding suited for Indian Ocean trade. Metallurgy was advanced, as evidenced by the rust-resistant Iron Pillar of Delhi from the fourth century CE. The caste system eventually segregated technical crafts into hereditary guilds, separating technological practice from scientific theory.

Following Hun invasions and the Gupta decline after 647 CE, India fragmented again. Islamic influence grew after 1000 CE, culminating in the Delhi Sultanate and Moghul Empire. Muslim rule introduced improved hydraulic technology and astronomical observatories, gradually supplanting traditional Hindu science in the north. Meanwhile, in the south, states like the Chola kingdom (800–1300 CE) continued large-scale irrigation projects, building vast tanks and dams. The most significant extension of this centralized hydraulic and scientific model occurred with the spread of Indian civilization to Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia.

Map 8.1. India. This map illustrates the geographical spread of Indian civilization from the Indus River Valley to the Ganges and southward. It specifically shows the extent of the Mauryan empire under Ashoka in the third century BCE, highlighting the first major political unification of the subcontinent.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;