The Engine of Empire: State-Driven Technology and Innovation in Imperial China

In traditional China, a profound schism existed between learned culture and the realm of practical technology. While calendrical astronomy and state-focused mathematics received scholarly attention, the vast majority of economic, military, and medical activities relied solely on empirical techniques divorced from theoretical research. Artisans and craftsmen, typically illiterate and of low social status, acquired skills through apprenticeship, operating without the benefit of scientific theory. Conversely, the literate scholar-official class, educated through years of classical study and enjoying high prestige, remained institutionally and socially segregated from manual crafts, a division reinforced by the civil service examination system and a value system that, akin to Hellenic Greece, often disdained hands-on technical work.

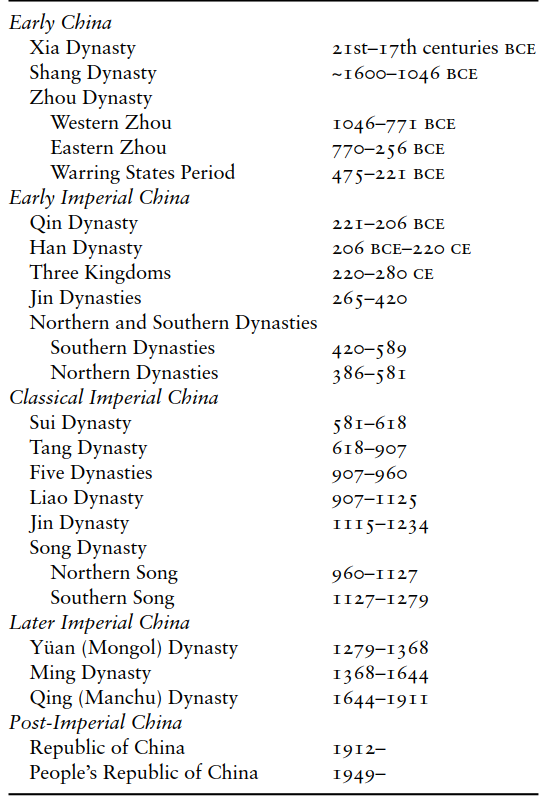

Table 7.1. A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties

Evaluating Chinese technological achievement requires looking beyond mere catalogs of "firsts," such as gunpowder, porcelain, or the fishing reel. While these attest to ingenuity, a more significant historical insight recognizes that the collective totality of its advanced technologies established China as the world's preeminent technological leader through the Song Dynasty and beyond. A defining characteristic was pervasive government control of industries, where the state nominally owned all resources and monopolized key production sectors like iron, salt, silk, and ceramics through official workshops. This system allowed the state to act as a merchant-producer, mobilizing vast cohorts of skilled craftsmen—sometimes hundreds of thousands—to meet its enormous administrative and military needs.

State management of the economy peaked during the Song period, when commercial taxes surpassed agricultural revenue. This spurred a monied economy, with coin minting exploding and leading to the world's first sustained use of paper money in 1024 CE. This financial technology's significance lies not merely in its invention but in its vital role in facilitating the scale and complexity of Song civilization. Similarly, hydraulic engineering formed a technological bedrock, exemplified by the massive Grand Canal. This state-directed infrastructure, requiring immense corvée labor for construction and maintenance, enabled the critical transport of grain from southern rice baskets to northern political centers, directly supporting imperial stability.

The ancient craft of pottery reached unprecedented artistic and technical heights, particularly with the perfection of porcelain during the Song. State-controlled kilns employed thousands in mass production, creating major commodities for tax revenue and thriving internal and international trade. Likewise, the textile industry, especially silk production, became highly mechanized, utilizing spinning wheels and water-powered reeling machines. Paper manufacturing, possibly derived from textile processes, became essential for bureaucratic administration, with evidence of its use dating to the Han Dynasty.

The bureaucratic state's dependence on records and standardization propelled advances in information technology. Although block printing emerged from earlier rubbing techniques, it was swiftly adopted by the state to print money, decrees, and handbooks. While movable type was invented in China circa 1040, the logographic nature of the script made woodblock printing more practical and efficient for centuries. Furthermore, China's superiority in iron production was staggering; by 1078 CE, output reached approximately 125,000 tons annually, fueled by innovative use of coke and water-powered bellows centuries before similar techniques appeared in Europe, primarily serving massive state armament production.

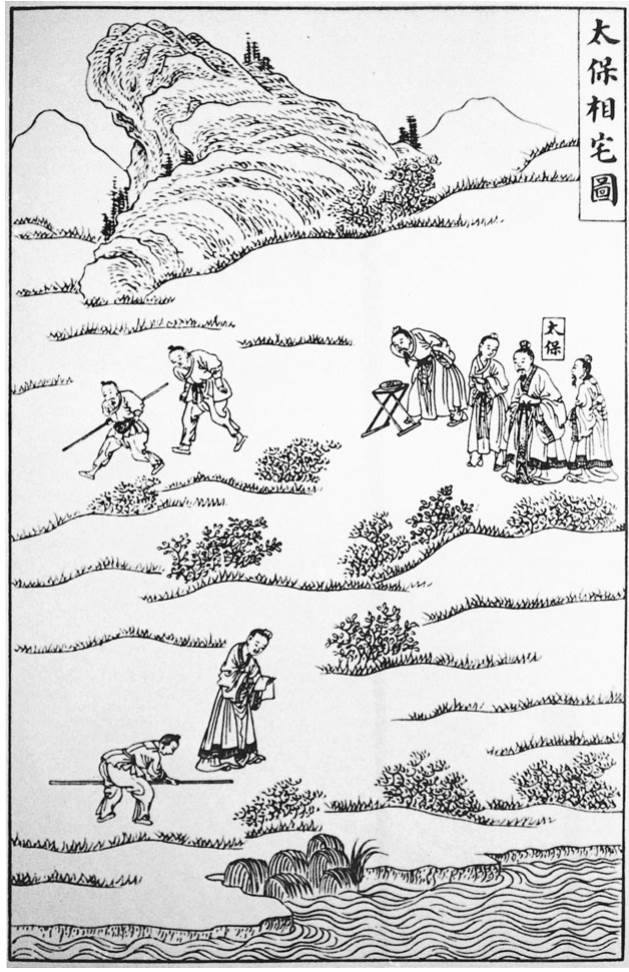

Fig. 7.2. Chinese geomancer. This illustrates a feng-shui master using a compass-like device to harmonize construction with natural energy flows (chi), demonstrating an early application of magnetic principles.

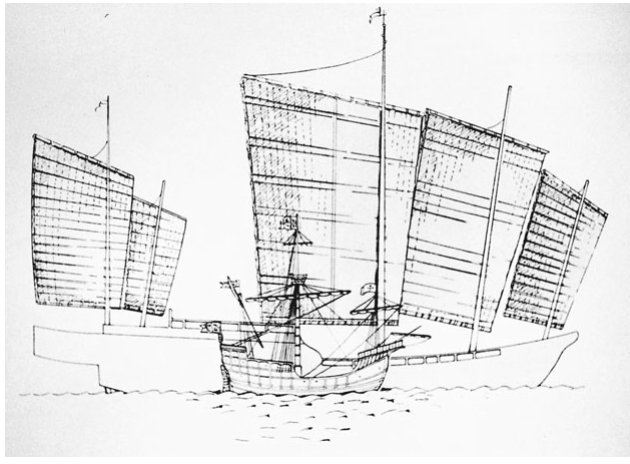

The transformative invention of gunpowder originated in alchemical traditions but was weaponized under Song pressure from foreign invasions, leading to rockets, grenades, and early guns. Conversely, the magnetic compass was first developed not for navigation, but for geomancy (feng-shui), showing how technology could spur natural philosophy. Its later maritime application supported the rise of the world's largest navy under the Song, Yuan, and early Ming dynasties. These fleets, featuring massive ships with watertight compartments and sternpost rudders, projected power across the Indian Ocean under Admiral Zheng He.

Fig. 7.3. European and Chinese ships. This comparative depiction highlights the vast scale of Ming treasure ships versus contemporary European vessels, underscoring China's brief naval supremacy.

However, after 1433, the Ming state abruptly halted expeditions and shipbuilding, turning inward. Explanations range from shifting imperial priorities and the immense cost of inland projects like the Grand Canal to political factionalism. This retreat coincided with a relative technological stagnation, leaving China a powerful but less dynamic civilization until later encounters with the West. The Chinese experience ultimately demonstrates how a centralized, bureaucratic state could drive technological sophistication to extraordinary heights, yet also constrain its trajectory and long-term evolution.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;