Applied Science and Technology: Analyzing the Complex Relationship in Modern Innovation

The long-standing promise of applied science, first evident with state support for scientific experts in ancient pristine civilizations during the fourth millennium BCE, reached its substantial realization only in the twentieth century. Contemporary investment from both government and industry has finally grown to match the historical rhetoric regarding science's utility. While the intellectual and social rapprochement between technology and science is characteristic of this era, the precise, intricate bonds connecting modern science and technology require careful examination and unraveling.

Indeed, science and technology today demonstrate a wide spectrum of connections. As evidenced, theoretical breakthroughs at the forefront of scientific research can be directly channeled into practical technologies. However, even within this direct application, variations exist. The development of the atomic bomb, for instance, involved a brief but distinct delay separating theoretical innovation from practical invention. Furthermore, the institutional separation of scientists conducting pure research from engineers handling development often preserves a classical distinction. In contrast, the invention of the laser by Gordon Gould in 1957 blurs this line, as the underlying physics and the practical device emerged simultaneously. Gould's subsequent role in developing and commercializing the laser further erodes neat categories of scientist, engineer, and entrepreneur, adding nuance to the concept of applied science.

In many sectors, however, it remains misleading to portray technology merely as directly "applied science." The education of technologists and engineers includes essential scientific principles, but rarely the most advanced theoretical science. Typically, simplified or "boiled down" science suffices for practical application. For example, NASA scientists and engineers launching the Apollo moon missions relied on Newtonian celestial mechanics perfected by Laplace, not cutting-edge relativity or quantum mechanics. This demonstrates that established scientific knowledge, rather than frontier research, frequently underpins monumental engineering achievements.

Even when scientific knowledge forms a foundational component, additional factors are so critical that labeling a technology as simply applied science is inadequate. Chester A. Carlson's 1938 invention of xerography, a dry-process photocopying method, utilized his boiled-down knowledge of optics and photochemistry. Yet, the utility of his invention was not immediately recognized, requiring years of persuasion to skeptical backers like IBM. Ultimately, perfecting a practical photocopying machine depended on engineering improvements, intuition, and a pivotal marketing decision to lease the devices—factors largely separate from pure science. This case illustrates how invention can precede and create necessity, rather than the reverse.

The existence of multiple competing designs for products like copy machines, televisions, or computers highlights a fundamental difference between contemporary science and technology. The scientific community converges on a single, agreed-upon solution for a given problem, such as the chemical structure of a protein. In contrast, science-based technologies routinely feature multiple viable design and engineering solutions. Some variations cater to different applications, while others exist primarily for competitive marketing purposes, underscoring technology's responsive and pluralistic nature.

The interactions between science and technology in the twentieth century thus span a significant spectrum. These range from "strong" direct applications, as seen with the laser or atomic bomb, to "weak" interactions involving boiled-down science, exemplified by Carlson's xerography process. Simultaneously, the traditional independence of technology from pure science persists. Innovations like the 1994 patented cat litter made from wheat (U.S. Patent 5,361,719) by Theodore M. Kiebke emerge from practical ingenuity with little connection to scientific theory, continuing independent traditions in engineering and crafts.

Across this entire spectrum of connections, applied science in its manifold forms has fundamentally transformed human existence and propelled industrial civilization to its current state. Science and science-based technologies are now integrally woven into the fabric of global societies and the world economy. To complete this analysis, a concluding examination of the contemporary state of science as a social institution is necessary.

The Scientific-Technological Revolution: 20th Century R&D Funding Trends and Priorities

The integration of science and technology into economic production represents a defining characteristic of the modern era. Marxist theorists in the former Soviet Union aptly termed this convergence the scientific-technological revolution, a concept highlighting the effective merger of research and practical application. This fusion has elevated science-based technologies from cultural achievements to powerful engines driving the economies and societies of the developed world and beyond. The scale of resources dedicated to this enterprise underscores its fundamental societal role.

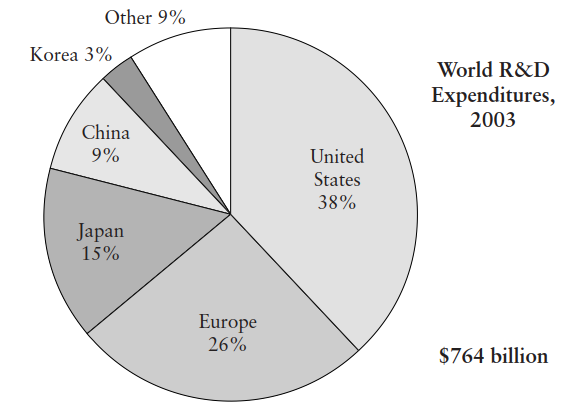

Global investment in research and development (R&D) quantifies this shift. In 2003, worldwide R&D expenditures totaled approximately $764 billion, led by the United States at $290 billion. When analyzed as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Sweden led in 2002 by dedicating 4.3% of its GDP to R&D, while the United States ranked fifth at 2.7%. These figures, illustrated in Figure 20.1, demonstrate the significant economic priority placed on scientific advancement by industrialized nations, with the U.S. share of global spending showing a relative decline.

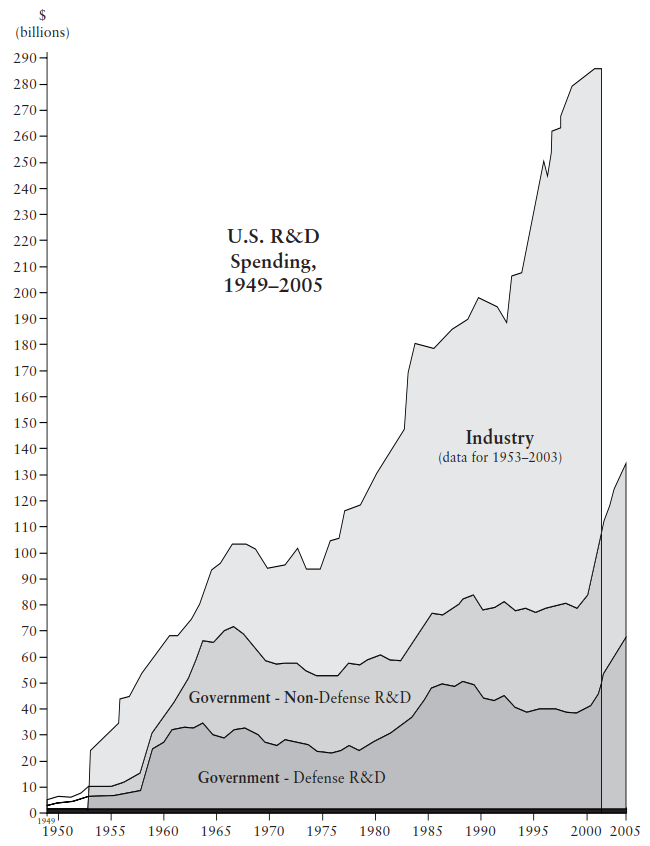

Historical analysis reveals an explosive growth in R&D funding, particularly following World War II. U.S. government science funding, for instance, grew from $160 million in 1930 to $1.52 billion by 1945. The Cold War, especially after the 1957 launch of Sputnik, triggered a sustained surge in both public and private investment. As shown in Figure 20.2, inflation-adjusted U.S. R&D spending nearly tripled since 1965, marking a historic prioritization of scientific research by government and industry.

The proportion of the U.S. federal budget allocated to R&D peaked at nearly 12% in the early 1960s before stabilizing between 3% and 5%. However, as a share of discretionary federal spending, R&D consistently claimed 12-15% of funds since the mid-1970s. This consistent allocation underscores its status as a budgetary priority, even amidst fluctuating total expenditures and competing fiscal demands.

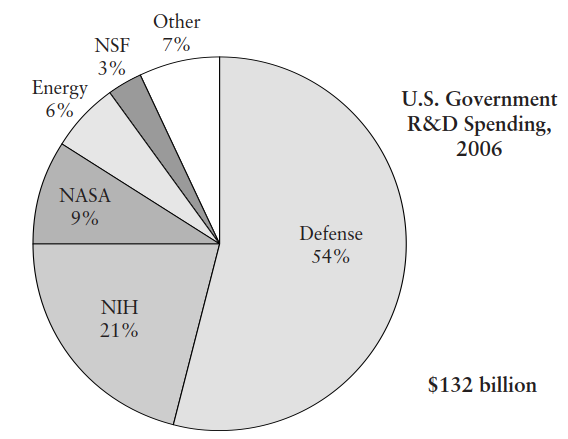

Throughout the Cold War, U.S. government science patronage was overwhelmingly driven by defense needs. In 2005, the Department of Defense R&D budget was $71 billion, more than double the $27 billion allocated to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Defense-related projects consistently consumed over half of all federal R&D dollars, as depicted in Figure 20.3. Furthermore, federal funding heavily favored applied science over pure research, with an approximate 80/20 split, nearing 100% applied within defense spending.

The hierarchy of U.S. federal R&D funding is revealing. The Defense Department and NIH are followed by NASA, the Department of Energy, and finally the National Science Foundation (NSF), which received a mere 3.2% of the federal R&D budget in 2005. The NSF itself increasingly directs grants toward strategic areas like the National Nanotechnology Initiative, explicitly linking science to national needs and economic growth.

International comparisons highlight the distinct defense orientation of U.S. R&D priorities. Unlike the United States and Great Britain, governments like Japan, Germany, and Italy in 2002 directed 50-60% of their R&D funds toward the advancement of knowledge. This contrast underscores a fundamental philosophical divergence in how nations perceive the primary purpose of public scientific investment.

Analyzing U.S. funding by discipline reveals a notable shift over time. Through the 1970s, support for physical sciences, life sciences, and engineering was roughly equal. Subsequently, funding for biology and the life sciences began to outpace other fields, mushrooming from the mid-1990s. By 2005, NIH's budget had grown two-and-a-half-fold since 1990 alone, with over half of nondefense R&D dedicated to health and life sciences—eight to ten times more than any other academic discipline.

Other fields have seen targeted growth. Mathematics and computer science funding quintupled since the 1980s for national security reasons, though in 2003 it remained a tenth of life sciences funding. Similarly, counterterrorism R&D increased six-fold after September 11, 2001, yet also plateaued at roughly one-tenth of biology funding. These trends illustrate responsive, mission-driven allocation within the broader federal portfolio.

Two major conclusions emerge from these funding patterns. First, the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union marked a watershed, shifting emphasis from the physical sciences and military hardware to the life sciences. Second, the biomedical revolution has had a profound impact, making the life sciences, due to their health and economic potential, the new primary focus of government interest and financial support.

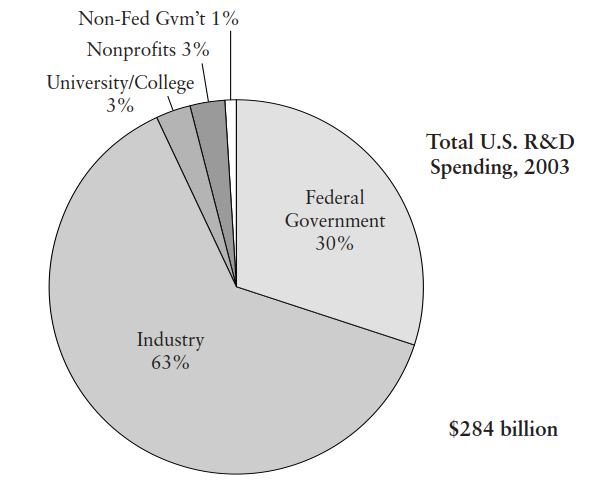

A seismic shift in the patronage for science occurred in the 1990s, as industry displaced government as the primary source of R&D funding. In virtually every developed nation, industry now outspends government, typically by a factor of two. In 2003, U.S. business and industry provided 63.3% of total R&D funds, as shown in Figure 20.4, with Japan and Korea exceeding 70%. Industry also performed 68.3% of all R&D work in the U.S.

However, industry investment is intensely focused on development and application. Analysis shows 71% of industry R&D spending goes to development (prototyping, marketing), 21% to applied research, and only 8% to pure research. This indicates that while industry is the dominant funder, its orientation is overwhelmingly toward immediately useful and profitable applications. This shift has also moved research focus from hardware toward information and altered traditional scientific career paths.

Despite its smaller share in basic research funding, the U.S. federal government remains its principal patron, providing 60% of such funds in 2003 compared to industry's 17%. Crucially, the government funds two-thirds of the R&D performed in colleges and universities, the primary locus of fundamental discovery. Thus, while industry dominates total expenditure, the foundational basic research underpinning future innovation remains largely taxpayer-supported through government grants to academia.

These global patterns confirm that the core rationale for funding science has remained consistent since antiquity: the pursuit of practical benefits. Although funded at historically unprecedented levels, scientific research continues to be harnessed by both governments and corporations for strategic, economic, and social gains. The scientific-technological revolution is thus characterized not only by the merger of knowledge and application but by its deep institutional and financial entrenchment within modern societal frameworks.

Figure 20.1. World spending on science and technology. Led by the United States, industrialized countries now spend almost three quarters of a trillion dollars on research on science and technology. The overall percentage of U.S. R&D expenditures has been declining steadily, and relative to its economy, the United States now ranks fifth in the world. Other countries devote proportionally more to non- applied research.

Figure 20.2. Growing support for science and technology. U.S. spending on research and development jumped dramatically with the Cold War and especially after the Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957. Through the mid- 1970s the U.S. government provided the bulk of these funds, but then private industry funding began to skyrocket.

Figure 20.3. Funding priorities. More than half of U.S. government spending on research on science and technology is allocated to defense. Almost all of defense-related spending supports applied science and technology. Only a small fraction of federal funds goes to non- applied research, notably in the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Figure 20.4. Industry driven. Private industry now out- spends the federal government on R&D by more than a two-to-one ratio, with funds going overwhelmingly to product development and applied research, especially in the life sciences. Research to advance knowledge in the Hellenic tradition takes place only here and there in universities, government, and industry.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;