The Evolution and Societal Impact of Computers: A Historical and Technological Analysis

The domain of applied science has fundamentally transformed technology and society through the development of the modern electronic computer. Its conceptual origins trace back to early automation, notably the Jacquard loom (1801), which utilized punch cards to control weaving patterns. Concurrently, the calculating demands of an industrializing society spurred inventions like the mechanical calculating engines conceived by Charles Babbage (1791-1871), who envisioned a universal computing machine. Advancements continued with electromechanical calculators in the 1930s, often funded by institutions like the U.S. Census Bureau for data processing. The catalytic effect of World War II accelerated progress, leading to landmark machines such as the Mark I calculator (1944) and the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) in 1946.

The post-war era saw the emergence of stored-program, general-purpose digital electronic computers, a paradigm based on theoretical foundations laid by Alan Turing (1912-1954) in 1937 and later expanded by John von Neumann. This led to the UNIVAC (Universal Automatic Computer), which became the first commercially available and mass-produced central computer in 1951. The pivotal scientifico-technical innovation enabling this evolution was the invention of the solid-state transistor in 1947 by William Shockley and his team at Bell Laboratories, earning him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1956. This device replaced unreliable vacuum tubes, permitting the development of practical, large-scale computers like the IBM 360 in the 1960s.

Further miniaturization led to the semiconductor computer chip, a triumph of materials science and engineering. This progression exemplified Gordon Moore's "Law" (enunciated in 1965), which observed that the number of transistors on a chip doubled approximately every eighteen months, driving exponential growth in computing power. This trend continued for decades as physicists worked at the nanometer scale, though eventual physical limits are anticipated. From the 1960s, mainframe computers from IBM and Digital Equipment Corporation became ubiquitous in military, banking, airline reservation, and academic contexts, with the computer center emerging as a novel social space.

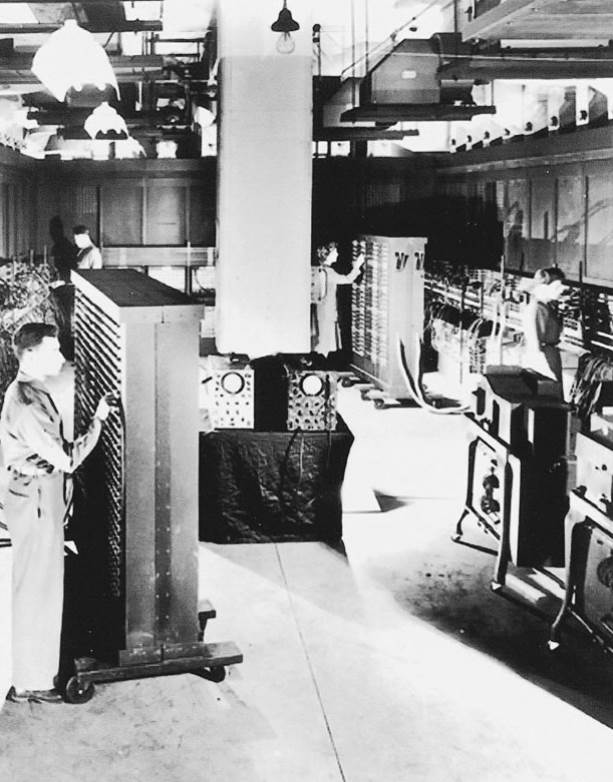

Fig. 19.3. Early computers. An electronic calculating behemoth with 18,000 vacuum tubes, the ENIAC machine (1946) filled a large room and consumed huge amounts of power.

Continual improvements spanned numerous realms: software and programming languages; the design and fabrication of silicon chips and integrated circuits; magnetic media like the floppy disk; and display technologies. However, the revolution truly democratized with the personal computer (PC) in the 1970s and 1980s. Initially built by hobbyists from kits, the market was catalyzed by the Apple II from Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak (1977) and the IBM PC (1981), which used the DOS operating system from Microsoft Corporation, led by Bill Gates. Innovations like the mouse and graphical user interface (GUI), developed at Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), alongside software for word processing and spreadsheets, transformed PCs into indispensable tools.

The proliferation of computing devices has become ubiquitous, forming the core of modern industrial civilization. While penetration was significant in nations like the United States, global per capita access in 2000 remained limited, indicating substantial room for growth. The transformative next phase was computer networking. Early connections used modems to link terminals to mainframes, but the seminal breakthrough was ARPANET in 1969, funded by DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency). This network, the precursor to the Internet, expanded to connect universities and popularized e-mail. By the 1990s, the World Wide Web enabled commercial development, creating today's global information system.

The Internet's essence lies in communication and information access, functioning as a substrate for e-mail and a universal digital library. Commercial search engines provide instantaneous access to vast information repositories, democratizing knowledge while presenting challenges regarding reliability. It also created a global marketplace, with companies like Amazon.com and eBay becoming landmarks. This liberation of information reduces reliance on traditional gatekeepers, though it creates a digital divide between those with and without access. The Internet fosters global, interest-based communities, offering a more interactive experience than passive mediums like television.

Computers have radically reshaped other industries. The music industry transitioned to digital storage and retrieval, using laser-read disks. The pornography industry expanded due to private digital access. Furthermore, computer and video games, driven by demands for processing power since Atari's PONG (1976), have become a major economic and cultural force, with modern game development budgets reaching tens of millions. Supercomputing advancements, initially for military use, eventually enhanced graphical capabilities accessible to PCs, enabling digital photography, video, and contributions to artificial intelligence and data mining.

Finally, the movie industry has been revolutionized through digital projection systems, digital animation, and computer-generated imagery (CGI), creating visual effects previously impossible. The ongoing developments in computing are remarkably recent, underscoring the rapid pace of change driven by high-tech industries in the twenty-first century and affirming the computer's role as a primary agent of continuous societal transformation. This ongoing evolution testifies to the profound and unfinished impact of this pivotal technology.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;