The Evolution and Impact of Scientific Medicine in Modern Healthcare

Contemporary medicine in the developed world represents a paramount achievement of applied science. The systematic exploitation of fundamental research in biology, chemistry, and physics has driven stunning advancements in pharmaceuticals, medical technologies, and clinical practice over recent decades. These sophisticated, science-based technologies have revolutionized the identification, understanding, and treatment of disease. Consequently, they have fundamentally transformed the experiences of both patients and physicians within the healthcare system.

The aspiration to link knowledge to healing is ancient, with elaborate theoretical frameworks emerging across diverse cultures from Islam and the West to China and India. While historical remedies exhibited varying efficacy, the core dream consistently connected natural philosophy to health. In the seventeenth century, René Descartes articulated the modern vision of scientific medicine, wherein practice would be perpetually advanced through research. This ideology began materializing in the nineteenth century with anesthesia, antisepsis, the germ theory of disease, and hospital modernization. Only in the contemporary era, however, has this vision been partially fulfilled, with science-based medical technologies flourishing globally within industrial civilization.

Medical practice has always constituted a set of technologies, with Western scientific medicine becoming thoroughly colonized by technological systems. This model is now institutionalized worldwide in hospitals and medical centers. Indeed, contemporary scientific medicine functions as a grand, integrated technological system, apparent to any patient or visitor. The technologies monitoring and improving health stem from a highly specialized, science-based craft practice, unparalleled in the pre-industrial history of medicine.

The traditional bedside practice model, focusing on the holistic patient, is no longer the norm, supplanted by increasingly depersonalized treatment within medicine's technological machinery. Today, patients are evaluated primarily through clinical data from diagnostic tests that define disease as deviations from established norms. This process leverages an exquisitely sophisticated battery of blood tests and other routine screening tests. Consequently, the patient's subjective experience often becomes less relevant, while physicians undergo extensive training to master the diagnostic technologies essential for modern practice. This necessity inherently distances physicians from treating the whole person.

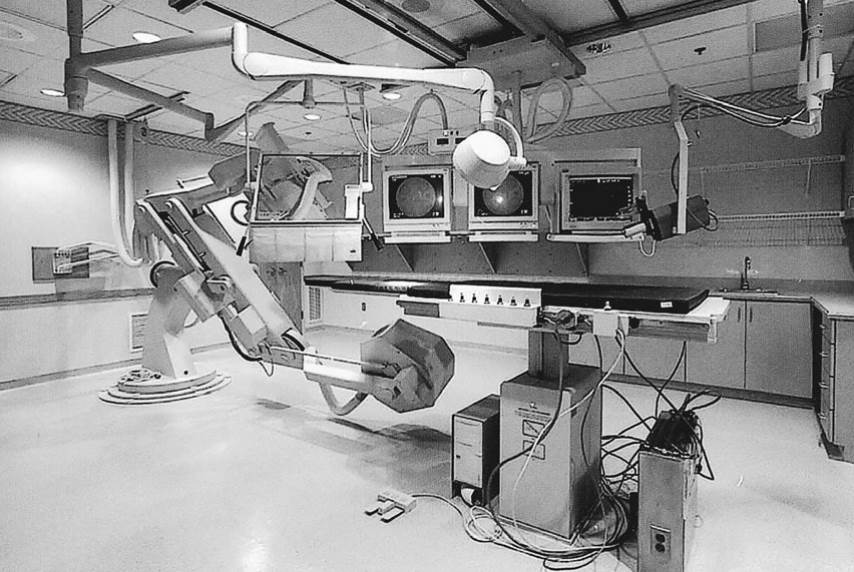

The hospital has evolved into an advanced center for science-based technologies, with the ordinary operating room epitomizing this modern miracle. Surgeons globally perform life-saving and happiness-increasing procedures in this technological setting. Open heart surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass, once esoteric, are now routine, aided by artificial heart-lung devices. Since Dr. Christiaan Barnard's first heart transplant in 1967, organ transplantation has become commonplace. While the fully artificial heart remains experimental, mechanical assists show great promise. The current trend favors minimally invasive surgeries using laparoscopic techniques and even fully robotic devices enabling remote operations. Extraordinarily complex procedures, like in utero surgery or separating conjoined twins, raise profound social and ethical questions regarding resource allocation.

Modern medicine is fundamentally reliant on science-based technology. The medical application of X-rays followed swiftly after their 1895 discovery, becoming the first in a series of powerful diagnostic tools rooted in scientific research. Digital X-ray technology and the CAT scan (computerized axial tomography) use X-rays and computers to generate detailed 3-D images. From nuclear physics, MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and PET scans (positron emission tomography) exploit atomic and radioactive properties for clinical imaging, with MRI earning a Nobel Prize in 2003. An array of other machines, including EKGs (electrocardiograms), EEGs (electroencephalograms), ultrasound, and digital thermometers, are ubiquitous in global medical facilities.

The development of pharmaceuticals represents another domain where scientific knowledge yielded immense medical and economic value. Sir Alexander Fleming's 1928 discovery of penicillin initiated the antibiotic age, a transformative "wonder drug" developed through medical research. World War II accelerated its mass production, fueling the explosive growth of a global pharmaceutical industry that reached $400 billion in sales by 2002. Dominated by multinational corporations, the industry invests heavily in research and development, with bringing a new drug to market costing hundreds of millions of dollars.

Fig. 19.2. High-tech medicine. This mobile catheterization unit is an exquisite piece of science-based medical technology available to privileged patients in Industrial Civilization today.

Within this intense research context, new drugs emerge through systematic experimentation and trials. The introduction of oral contraceptives ("The Pill") in the 1960s was a landmark, granting women greater reproductive control and fueling social change. The industry produces an impressive range of chemical and biological compounds for myriad conditions, including antidepressants like Prozac, anti-inflammatories, cholesterol-lowering drugs, and proton pump inhibitors (PPI) for acid reflux. This system sometimes appears to create diseases for which it markets chemical treatments, a phenomenon underscored by direct-to-consumer drug advertising. Drugs for sexual dysfunction, such as Viagra, further illustrate this dynamic.

Beyond pharmacy, other scientific triumphs have profoundly impacted public health. The 1911 discovery of vitamins enabled the prevention of deficiency diseases. Building on Louis Pasteur's work, twentieth-century vaccines against diseases like typhoid, tetanus, and measles dramatically reduced mortality. The polio vaccines developed by Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin in the 1950s yielded tremendous public health benefits. Additionally, in vitro fertilization (IVF), since 1978, exemplifies high-tech medical science, helping countless couples conceive while raising novel ethical and legal questions.

Materials science and biomedical engineering have yielded fruitful medical applications. Innovations include artificial joints, limbs, dialysis equipment, pacemakers, digital hearing aids, and cochlear implants. Dentistry, too, has been transformed by advanced dental technologies and materials, such as the modern dental crown. The future promises ever more sophisticated technologies, including artificial blood, stem cell therapy for regeneration, and advanced vaccines. Emerging fields like nanotechnology envision microscopic devices for targeted drug delivery or microsurgery, while pharmacogenomics aims to tailor drugs to individual genetic profiles.

The successes of scientific medicine are undeniable, contributing to the near-eradication of polio and smallpox and unprecedented increases in life expectancy. A female born in Japan today can expect to live 83.9 years, a stark increase from U.S. life expectancy of 49 years in 1901. This longevity creates aging populations, with nearly 20% of Japan's population over 65, presenting significant social and economic challenges for healthcare and pension systems.

Nevertheless, this model presents a mixed legacy. The vision of omnipotent scientific medicine was challenged by disasters like Thalidomide in the late 1950s, a sedative that caused severe birth defects. Regular drug recalls fuel skepticism about the long-term evaluation of pharmaceuticals and the marginalization of non-drug alternatives. Furthermore, industrial civilization generates its own medical challenges, including antibiotic-resistant bacteria from overuse, the global spread of diseases like SARS or HIV, and epidemics of diabetes and obesity linked to lifestyle.

The dominance of profit-driven pharmaceutical companies can skew research and healthcare provision, often at the expense of preventive medicine or less lucrative avenues like vitamin and vaccine research. This, coupled with the exorbitant cost of high-tech procedures, exacerbates global and domestic inequalities in healthcare access. The majority of the world's population lacks access to advanced medical services, raising critical political and ethical questions about resource distribution. This disparity constitutes the central paradox of medicine in industrial civilization: offering miraculous technological advances while failing to provide equitable access, thereby prompting many to seek alternative medical traditions for saner, healthier lives.

DNA Structure Discovery & Modern Applications: Genetics in Medicine, Agriculture, and Forensics

The 1953 discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA by James Watson and Francis Crick fundamentally transformed biological science, providing the definitive molecular explanation for heredity and life processes. This foundational knowledge has propelled the development of advanced DNA technologies, which now form the cutting edge of 21st-century applied science with profound implications across medicine, agriculture, and forensic science. The journey from esoteric knowledge to widespread application required a series of critical technical breakthroughs. The initial Nobel Prize-winning discovery was followed by the elucidation of the genetic code in 1966, which linked DNA sequences to protein synthesis, enabling practical genetic work.

A pivotal advancement occurred in 1972 with the development of recombinant DNA techniques, allowing scientists to cut and paste genetic material between different organisms. This was complemented by electrophoresis gel technologies for precise molecular comparison of DNA samples. The 1985 invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by Kary B. Mullis of Cetus Corporation revolutionized the field by enabling exponential amplification of minute DNA sequences, facilitating industrial-scale genetic analysis. Mullis's 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry underscores PCR's transformative role, with thousands of laboratories now specializing in these analytical techniques.

A monumental achievement in genomics was the Human Genome Project (HGP), an international "Big Science" endeavor launched in 1990 to sequence the entire human genome. The project faced competition from the private firm Celera Genomics, led by Dr. J. Craig Venter, which spurred an unprecedented public-private collaboration. By 2003, the completed sequence—detailing approximately three billion base pairs and 20,000-25,000 genes—was published, providing an invaluable research framework for decades. The HGP's success, completed under its $3 billion budget due to rapidly falling sequencing costs, also catalyzed the comparative genomics of other species, from model organisms like mice to agriculturally important ones like cattle.

The commercialization of genetic knowledge is extensive, with a vibrant biotechnology industry emerging around proprietary DNA sequences and techniques. Pioneering companies like Genentech, founded in 1981, have grown into multi-billion dollar enterprises, often clustering near major research hubs in Boston, San Francisco, and San Diego. This has intensified focus on intellectual property protection for genetic discoveries. A notable example is the 1998 initiative by deCODE Genetics in Iceland to build a population-wide genetic database to isolate disease genes, highlighting both the power and the ethical complexities of commercialized genomic data.

Perhaps the most widespread impact of applied genetics is in agriculture, driving a revolution through genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Engineered crops like genetically modified corn, soybean, and cotton are now cultivated globally (except largely in Europe), reducing pesticide use and entering most processed food chains. Beyond crop science, genetic testing for diseases has become a critical medical application. Screening for conditions like Tay-Sachs disease and Down syndrome allows for carrier counseling and prenatal diagnosis, though it also fuels a consumer-driven neo-eugenics movement with significant ethical and insurance-related ramifications.

Cloning, exemplified by the 1996 creation of the sheep Dolly, represents another frontier, offering potential in animal husbandry and endangered species preservation while raising profound ethical questions regarding human application. In law enforcement, DNA databases and PCR analysis have revolutionized forensics, providing a tool more reliable than fingerprints for identifying individuals. However, the storage of DNA profiles from felons and military personnel raises serious concerns about privacy and civil liberties. Ultimately, while DNA technology offers remarkable power for human benefit, it also presents a dual-use dilemma, enabling possibilities ranging from personalized medicine to the threats of bioterrorism, leaving society to navigate its profound implications.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;