The Manhattan Project and the Dawn of the Atomic Age: Science, Government, and Technological Legacy

The development and deployment of the atomic bomb by the United States during World War II represents a definitive watershed in modern history, fundamentally altering the relationship between science, government, and technology. This event uniquely demonstrated the immense practical potential of cutting-edge scientific theory when paired with large-scale, state-funded research and development initiatives. The convergence of these factors established a powerful new paradigm for applied science, permanently transforming traditional institutional dynamics and public perception. The legacy of this endeavor continues to influence scientific, military, and technological policy on a global scale.

The foundational science enabling the bomb emerged just prior to the war. In 1938, German physicist Otto Hahn demonstrated nuclear fission, the splitting of heavy uranium atoms. The following year, Austrian-Swedish physicist Lise Meitner provided the theoretical explanation and calculated the vast energy release possible from a nuclear chain reaction. Recognizing the peril if Nazi Germany developed such a weapon, Allied scientists, including Albert Einstein, alerted President Franklin Roosevelt. This prompted initial research, which escalated into the full-scale Manhattan Project after the U.S. entered the war. Under the command of General Leslie Groves, this colossal effort involved tens of thousands of personnel across dozens of sites at a cost of billions.

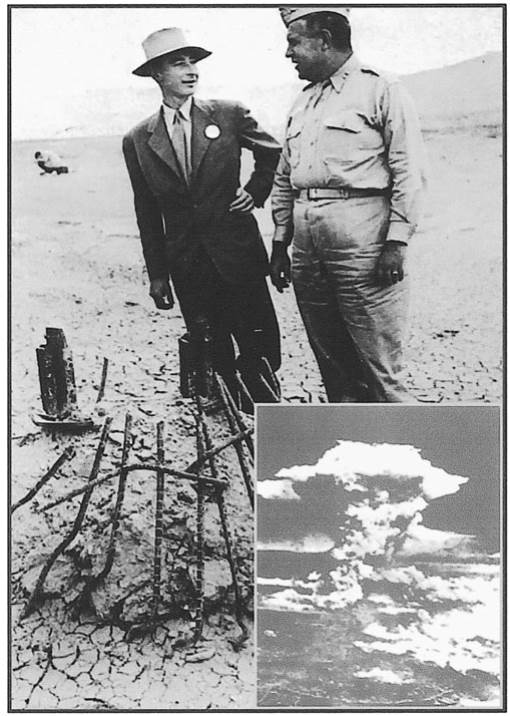

A series of pivotal scientific milestones followed rapidly. In December 1942, beneath a University of Chicago football stadium, Italian emigré physicist Enrico Fermi achieved the first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. This critical proof of concept fueled the bomb's development at the secret Los Alamos laboratory, directed by physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. On July 16, 1945, the first atomic device was successfully detonated at the Trinity test site in New Mexico. Mere weeks later, the uranium-based "Little Boy" bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, followed by a plutonium-based bomb on Nagasaki on August 9, leading to Japan's surrender and the war's end.

Fig. 19.1. The Atomic Age begins. J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie R. Groves inspect the remains of the Trinity test site following the first explosion of a nuclear bomb (New Mexico, July 16, 1945). Inset: The “Little Boy” atomic bomb exploding over Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945.

The bomb's immediate impact concluded World War II but catalyzed the ensuing Cold War, triggering a frantic arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union. The competition quickly advanced from atomic fission bombs to vastly more powerful thermonuclear or hydrogen bombs, which derive energy from nuclear fusion. The war had already seen other successful government-led applied science projects, including radar, penicillin mass production, and early computing. The Manhattan Project's success, however, solidified a new model of direct, large-scale state investment in science for strategic technological payoff, effectively fusing the concepts of fundamental research and applied technology in the public and political consciousness.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower's 1961 warning about the growing influence of the "military-industrial complex" directly stemmed from this new paradigm. Government-funded, science-based military research, much of it classified, has continued at massive scales, extending far beyond nuclear weapons into areas like global telecommunications, "smart" weaponry, and remote battlefield systems. This enduring partnership drives innovation in lethality and sophistication, with contemporary security and anti-terrorism research following the same model of leveraging cutting-edge science for immediate application.

A significant peaceful offshoot of this research was the nuclear power industry, which merged atomic physics with civilian electrification. While growth has slowed, countries like France remain heavily reliant on nuclear energy. Furthermore, the exploration of space was a direct outgrowth of the science-military nexus. German V-2 rocket technology, pioneered by Wernher von Braun, evolved into the intercontinental ballistic missiles of the Cold War. The Soviet Union's launch of Sputnik I in 1957 and Yuri Gagarin in 1961 ignited the Space Race, culminating in the U.S. Apollo program and the 1969 Moon landing. Subsequent endeavors, including the Space Shuttle, International Space Station, and national programs in China and Japan, remain rooted in this legacy of state-driven technological ambition for political and scientific prestige.

Thus, the Atomic Age initiated by the Manhattan Project established an indelible template. It permanently entwined state power with scientific enterprise, redefined technology as applied science, and set in motion continuous cycles of innovation driven by geopolitical competition. The enduring infrastructures of nuclear energy, space exploration, and advanced digital and weapons systems all trace their origins to this seminal fusion of theoretical discovery, government mobilization, and engineering application that characterized the mid-twentieth century.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;