The Neo-Darwinian Synthesis: Evolution from Darwin to DNA and Modern Debates

The disciplines of physics and cosmology provide fundamental frameworks for understanding the universe. Equally transformative, twentieth-century biology revolutionized our conception of living organisms and life's history on Earth. This reformulation fundamentally altered our worldview and reoriented numerous disciplines within the life and physical sciences. While evolutionary principles now underpin modern biological research, their acceptance and application sparked extensive interdisciplinary debate.

By the end of Charles Darwin's life in 1882, his theory of evolution by natural selection faced significant scientific contestation and was relegated to a lesser role. The early 1900s witnessed a confluence of scientific trends that revitalized Darwinian thought, culminating in the Neo-Darwinian synthesis. Critically, discoveries in physics, including radioactivity and Einstein's mass-energy equivalence, invalidated Lord Kelvin's restrictive age estimates for Earth. Consequently, estimates for the solar system's age expanded to billions of years, providing the vast temporal canvas necessary for evolutionary processes.

The simultaneous rediscovery of Gregor Mendel's principles of particulate inheritance at the century's onset was pivotal. Mendel's plant hybridization experiments demonstrated that heredity operates via discrete units, not blending. Concurrently, Hugo de Vries proposed a mutation theory, introducing macromutations as a mechanism for rapid variation. Ironically, these discoveries initially led some scientists to marginalize natural selection, believing Mendelian inheritance and mutation alone could explain evolution. The definitive synthesis emerged in the 1940s, recognizing that genes—the discrete hereditary units—combine in complex patterns to produce the subtle variations upon which natural selection acts.

Advances in cytology were crucial. Prior to 1900, improved staining techniques revealed chromosomes, thread-like nuclear structures. In the 1880s, August Weismann speculated they carried hereditary units, a hypothesis confirmed in the 1910s-1920s. Thomas Hunt Morgan and his team, using the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, experimentally confirmed Mendel's laws and the chromosomal theory of inheritance. In parallel, R. A. Fisher and population geneticists mathematically showed how a single advantageous variation could spread through a population. These threads unified in seminal works like Theodosius Dobzhansky'sGenetics and the Origin of Species(1937), Julian Huxley'sEvolution: The Modern Synthesis(1942), and Ernst Mayr'sSystematics and the Origin of Species(1942), forging a comprehensive evolutionary theory aligned with Darwin's original doctrine.

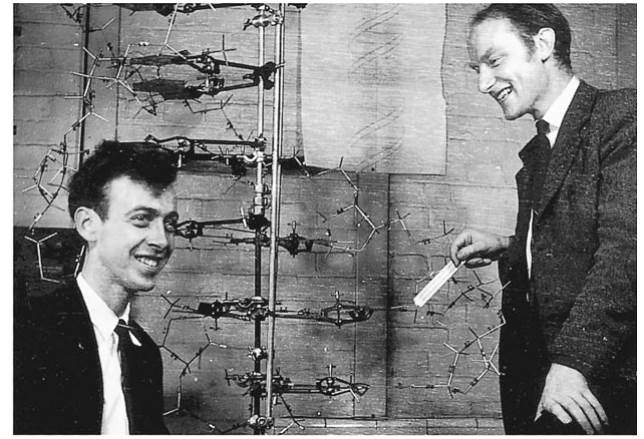

However, the biochemical basis of heredity remained unknown. By the 1940s, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was identified as a key nucleic acid. In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick deciphered DNA's molecular structure. Utilizing Rosalind Franklin's X-ray diffraction data, they proposed the double helix model, an elegant structure explaining inheritance and variation mechanisms—a landmark achievement earning them the 1962 Nobel Prize. This discovery represented the culmination of a century's inquiry, reducing the code of life to chemistry.

Fig. 18.3 . The double helix. The discovery of the double helical structure of DNA by James Watson and Francis Crick in 1953 demonstrated the material basis of inheritance and the substrate for how new variations can lead to species change. Their discovery marked the beginning of a new era in genetics and biochemistry.

While Darwinian evolution is the guiding paradigm in biology, its implications in other arenas remain contentious. From its inception, by substituting natural for divine processes, it clashed with religious orthodoxy, particularly in the United States. The 1925 Scopes "Monkey Trial" exemplifies this conflict. Debates persist today regarding the teaching of evolution versus "scientific creationism" and "intelligent design" in public schools. Within mainstream theology (fundamentalism excepted), many authorities accommodated evolution through non-literal scriptural interpretation, allowing for divine intervention in imbuing humans with a soul during physical evolution.

In the social sciences and philosophy, applying Darwinian concepts to human nature provoked fierce conflict. Social Darwinism emerged, claiming social organization and class stratification resulted from a biological struggle for survival. In the U.S., it was used to justify racial, ethnic, and class inequalities as hereditary and immutable. This ideology supported diverse positions, from Andrew Carnegie's laissez-faire capitalism in Gospel of Wealth to specious justifications for Nazi racial policies, eugenics, and forced sterilization. Since the 1960s, mainstream social science has repudiated such applications.

Paleontological discoveries profoundly shaped twentieth-century understanding of human evolution. While Darwin postulated human descent from simian ancestors, a coherent narrative is a modern product. Fossil discoveries now outline a sequence from australopithecines (like A. afarensis, "Lucy"), through Homo habilis, Homo erectus, to varieties of Homo sapiens. The exposure of the fraudulent Piltdown Man in 1950 cleared a major obstacle. Ongoing research continues to refine this picture, as with the 2004 discovery of Homo floresiensis, a diminutive, tool-using species that coexisted with modern humans until 12,000 years ago, challenging standard timelines.

While physical human evolution is widely accepted, extending evolutionary principles to human behavior faced resistance. Emile Durkheim's principle that social facts require social explanations erected a barrier between biological and social sciences, marginalizing biological approaches for decades. This began changing in the 1930s with the rise of ethology, founded by Konrad Lorenz, which highlighted genetic bases of behavior. The 1975 publication of Edward O. Wilson'sSociobiology, suggesting human sociality could be studied through Darwinian lenses, ignited controversy, accused of promoting "biological determinism." Nevertheless, research in sociobiology and evolutionary psychology has expanded, proposing evolutionary accounts for behaviors like altruism, cooperation, and incest taboos, gaining increasing scientific acceptance.

Darwinism's final triumph required supplanting Lamarckism, the idea that acquired characteristics are heritable. Its appeal lay in proposing direct environmental influence and rapid evolutionary change. Though Darwin considered it, and it saw brief favor in the mid-20th century (e.g., in the Soviet Union), it was ultimately repudiated. The "Central Dogma of Molecular Biology" asserts information flows from DNA to protein, not backwards, though mechanisms like retroviruses complicate this picture. The chemistry of the double helix ultimately invalidated Lamarckian inheritance.

Watson and Crick's 1953 breakthrough provided the mechanistic basis for heredity and evolution. That same year, the Miller-Urey experiment demonstrated that amino acids—life's building blocks—could form under simulated early-Earth conditions, supporting abiogenesis. Alternative hypotheses for life's origin include catalytic clays or panspermia (an extraterrestrial origin, entertained by Crick), though these shift rather than solve the ultimate question.

Molecular biology refined life's history. While Darwinian natural selection remains the core perspective, new tools like cladistics, molecular clocks, and mitochondrial DNA analysis allow scientists to quantify evolutionary rates and relationships. Active scientific debates persist on topics like avian descent from dinosaurs and whether evolution is gradual or punctuated. While some groups misrepresent these healthy debates as weaknesses, they represent normal scientific discourse. A universal consensus exists on the fundamental tenets that species are products of evolution and natural selection is its primary mechanism. The biological sciences have thus traveled a path mirroring Darwin's own journey—from theological explanation to the recognition that life's magnificent diversity is nature's artifact.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;