The Einsteinian Revolution: Redefining Space, Time, and Matter in 20th Century Physics

The most profound achievement of twentieth-century science was the overturning of the Classical World View of nineteenth-century physics and its replacement by revolutionary new frameworks for understanding physical reality. Termed the Einsteinian Revolution, this paradigm shift decisively shaped our modern conception of the natural universe. A previous synthesis, the Classical World View, was built upon a Newtonian framework of absolute space and time, immutable atoms, and a luminous ether that facilitated electromagnetic wave propagation. Its principles, governed by the laws of thermodynamics, offered a coherent and harmonious model that dominated late-1800s physics.

Unlike Aristotle's enduring system, this classical edifice collapsed rapidly under the weight of experimental anomalies. Beginning in the 1890s, a series of discoveries precipitated a fundamental crisis. The 1887 Michelson-Morley experiment, designed to detect Earth's motion through the ether, famously yielded a null result, contradicting classical predictions. Although this later became a cornerstone for relativity, physicists initially sought ad hoc explanations to preserve the ether concept. Concurrently, Wilhelm Roentgen's 1895 discovery of X-rays expanded the known electromagnetic spectrum and challenged conventional laboratory wisdom.

More disruptive revelations soon followed. In 1897, J. J. Thomson identified the electron, a particle nearly 2,000 times smaller than a hydrogen atom, proving atoms were not indivisible. Radioactivity, discovered by Antoine-Henri Becquerel in 1896 and named by Marie Curie in 1898, demonstrated that heavy elements like uranium spontaneously emit radiation and decay into other elements. This transformation directly violated the classical tenet of atomic immutability.

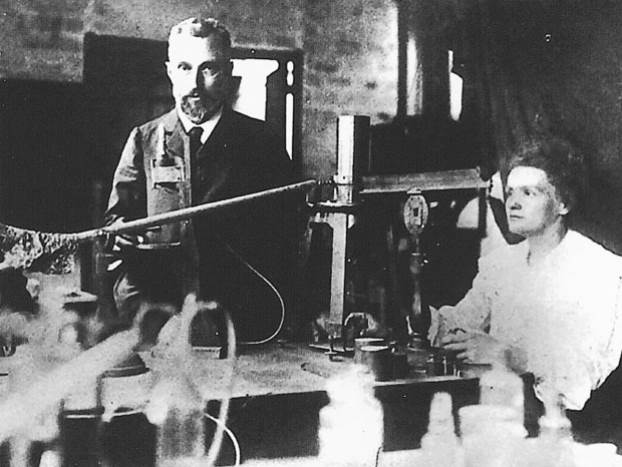

Fig. 18.1. Radioactivity. Pierre and Marie Curie in the “discovery shed” at the School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry, Paris, ca. 1900. Their discovery of radioactive elements and radioactive decay undermined received notions of the immutability of atoms.

Additional puzzles compounded the crisis. The photoelectric effect, discovered by Heinrich Hertz, defied classical wave theory as light only ejected electrons above a specific frequency threshold. The black body radiation problem suggested a theoretical infinite energy output, an absurdity contradicting thermodynamics. Max Planck's 1901 solution proposed that energy exists in discrete packets or quanta, not a continuous stream, seeding quantum theory. Albert Einstein matured intellectually during this turbulent period, his position as a patent clerk outsider allowing him to challenge entrenched dogma.

In his 1905 "miracle year," Einstein published groundbreaking papers that redirected modern physics. His paper on special relativity addressed uniform motion by positing the constant speed of light as a universal limit. This reformulation discarded Newton's absolute space and time, making measurements of time, length, and mass relative to the observer's frame of reference. A profound consequence was the mass-energy equivalence principle encapsulated in the iconic equation E = mc², unifying concepts held strictly separate in Classical physics. This was not a mere extension but a revolutionary transformation of foundational concepts.

Einstein later expanded this with his 1915 theory of general relativity, addressing accelerated motion and gravity. He proposed the equivalence principle, where gravitational forces are indistinguishable from acceleration effects. This redefined gravity not as a force but as the curvature of a four-dimensional space-time continuum by mass. Observations during the 1919 solar eclipse confirmed his prediction that starlight bends around the sun, validating the theory. By the 1920s, the classical universe of absolutes and ether was obsolete, replaced by Einstein's conceptually new cosmos.

Parallel developments in atomic physics proved equally consequential. Einstein's 1905 paper on the photoelectric effect supported Planck's quantum hypothesis. Following the electron's discovery, Ernest Rutherford's 1911 experiments revealed the atom as mostly empty space with a dense nucleus. His planetary model, refined by Niels Bohr, depicted electrons orbiting the nucleus, but it failed to explain stability or discrete energy emissions, leading to the new quantum mechanics.

The Copenhagen interpretation, developed around Bohr's institute, introduced a radical probabilistic view of nature. It proposed the wave-particle duality, where entities like electrons exist as probability waves until measured. In 1926, Werner Heisenberg's matrix mechanics and Erwin Schrödinger's wave mechanics were shown to be mathematically equivalent, solidifying the theory. Heisenberg's 1927 Uncertainty Principle established fundamental limits, stating that one cannot simultaneously know a particle's exact position and momentum, embedding inherent indeterminacy into nature.

This new physics classified subatomic particles into hadrons (e.g., protons, neutrons), leptons (e.g., electrons), and bosons (force carriers). The Standard Model emerged, describing hadrons as composites of quarks and mediating forces via bosons like photons. Particle accelerators, such as the Tevatron at Fermilab, discovered hundreds of particles, including the top quark (1995) and the tau neutrino (2000), confirming the model's predictions. Research continues for particles like the Higgs boson and the theoretical graviton.

The central unresolved challenge in theoretical physics is unifying general relativity (the large-scale) with quantum mechanics (the small-scale). String theory (later M-theory) emerged as a candidate for a quantum theory of gravity, proposing fundamental entities as vibrating one-dimensional "strings" in multiple dimensions. While promising for a Grand Unified Theory, it remains experimentally unverified. The quest to understand nature's fundamental forces and constituents, from the electroweak unification to a potential Theory of Everything, continues to define the frontier of physics, a sophisticated legacy of the revolutionary upheavals begun in the early twentieth century.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;