Aristotle: The Foundation of Western Science and His Enduring Intellectual Legacy

The work of Aristotle (384–322 BCE) represents a watershed in the history of human knowledge. His encyclopedic investigations, spanning logic, physics, cosmology, psychology, natural history, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics, culminated the Hellenic Enlightenment and established the foundational agenda for science and philosophy for nearly two millennia. Aristotle's methodologies and worldview dominated scientific traditions in late antiquity, the medieval Islamic world, and early modern Europe, defining research parameters until the Scientific Revolution. His systematic approach provided a comprehensive framework for understanding nature, securing his unparalleled influence across diverse cultures and epochs.

Born in Stagira, Thrace, to a privileged family—his father served as physician to the Macedonian king—Aristotle traveled to Athens as a teenager to study under Plato at the Academy. He remained there for twenty years before departing after Plato's death in 347 BCE. Following travels around the Aegean, King Philip II of Macedonia summoned him to tutor his son, the future Alexander the Great. After Alexander's ascension in 336 BCE, Aristotle returned to Athens to found his own school, the Lyceum. Political turmoil following Alexander's death prompted his departure from Athens in 323 BCE, and he died the following year. The extensive corpus attributed to him was compiled both during his life and by disciples, preserving complete works unlike the fragmented remains of his predecessors.

From a sociological perspective, Aristotle, like all Hellenic scientists, conducted research free from state direction or formal institutional affiliation. The Lyceum was his own teaching grove, not an officially sanctioned institution. This positioned him as an independent, leisured intellectual, a status he deemed essential for theoretical pursuit. Consequently, his studies were abstract, deliberately divorced from practical applications in engineering, medicine, or statecraft. Even his anatomical and biological research aimed not at medical utility but at understanding living beings within a rational cosmology. His theory of motion, influential until the 17th century, was part of a purely theoretical program.

Aristotle explicitly distinguished pure science from technology. He argued that after practical arts were secured, leisure enabled the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, driven by wonder and a desire to escape ignorance. This philosophical stance is consistent with historical analyses showing Hellenic scientists favored theoretical over practical orientations by a rough ratio of four to one. The power of Aristotle's system stemmed from its unified and universal character, offering a coherent, intellectually satisfying vision of the natural world and humanity's place within it, a scope of explanatory ambition that remains unequaled.

Aristotle’s physics is rightly termed the science of common sense, validating sensation and observation as the primary routes to knowledge. Unlike Plato’s transcendentalism or Pythagorean quantitative abstractions, Aristotle's views consistently aligned with everyday experience. He emphasized the sensible qualities of things, making his natural philosophy more accessible and scientifically promising for his time. His theories conformed to plain observation, requiring no radical reeducation of the senses, which cemented their broad acceptance and longevity.

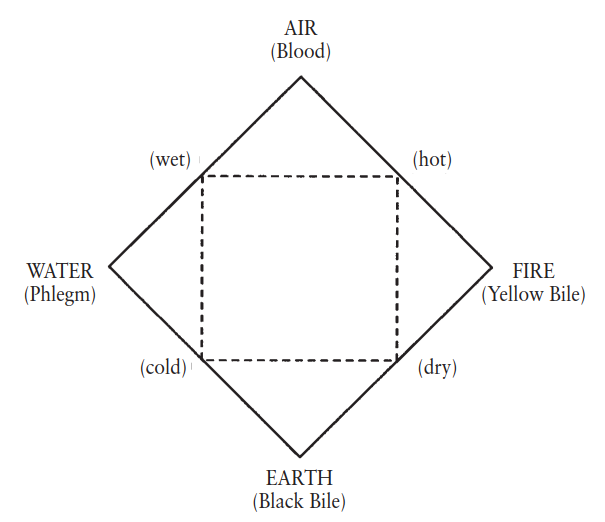

Central to his worldview was a qualitative theory of matter. Adopting Empedocles' four elements—earth, air, fire, and water—Aristotle theorized they were composed of paired fundamental qualities: hot, cold, wet, and dry, projected onto a featureless prima materia (first matter). As figure 4.5 illustrates, water combines cold and wet, fire is hot and dry, air is hot and wet, and earth is cold and dry. This system explained observable phenomena, like boiling water transforming into "air" by substituting hot for cold. Importantly, this qualitative theory provided a philosophical basis for alchemy, as altering qualities on the prima materia theoretically allowed transmutation of substances.

Fig. 4.5. The Aristotelian elements. In Aristotle’s matter theory, pairs of qualities (hot-cold, wet-dry) define each of the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. Substitute one quality for another, and the element changes. Each of the four elements also came to have an associated “humour,” which connected Aristotle’s views on matter with physiology and medical theory.

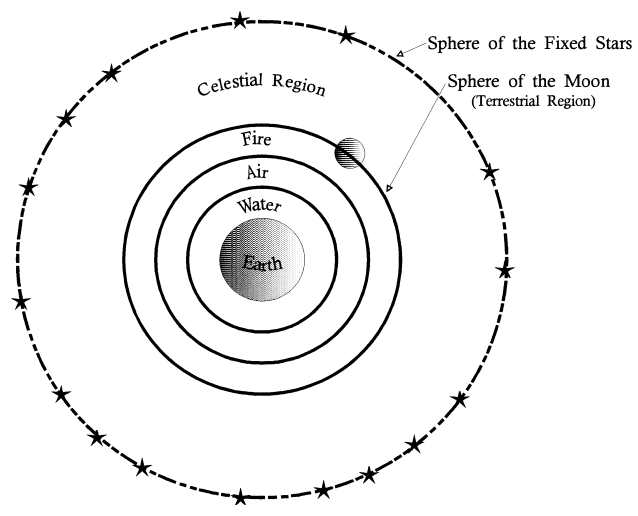

In Aristotle's cosmology, each element possessed a natural place and a corresponding natural motion. Heavy elements like earth and water moved rectilinearly downward toward the cosmic center (Earth), while light elements like air and fire moved upward away from it. This resulted in a concentric geocentric universe with terrestrial spheres of earth, water, air, and fire. His physics supported a spherical, motionless Earth at the cosmic center; displacing it would cause it to naturally return. He confirmed Earth's sphericity through lunar eclipse shadows and offered common-sense arguments against terrestrial motion, such as objects falling straight down.

Fig. 4.6. The Aristotelian cosmos. According to Aristotle, each of the four elements has a “natural place” in the universe. In the terrestrial region (to the height of the moon), earth and water move “naturally” in straight lines downward toward the center of the cosmos (Earth), while air and fire “naturally” move in straight lines upward and away from the center. The sphere of the moon separates the terrestrial region, with its four elements (including fiery meteors and comets), from the celestial region—the realm of the fifth, “aetherial” element whose natural motion is circular. The stars and planets reside in the celestial region and take their circular motions from the aetherial spheres in which they are embedded.

Aristotle's cosmology posited a sharp distinction between the sublunary (terrestrial) and celestial realms. Below the Moon, the four elements existed in a state of change and corruption. Above the Moon lay the perfect, incorruptible celestial realm composed of a fifth element, the quintessence or aether, whose natural motion was circular. This dual physics—separate laws for heaven and Earth—aligned with observation: celestial bodies appeared unchanging and moved in circles, while terrestrial phenomena were mutable. This coherent system remained dominant until Newton proposed a unified physics.

Motion not intrinsic to an element's nature—violent or forced motion—required an external mover in constant contact. While this explained most phenomena (e.g., a horse pulling a cart), it struggled with projectile motion like an arrow's flight, where Aristotle suggested the medium (air) continued the push. He also posited quantitative relationships: velocity is proportional to applied force and inversely proportional to resistance. This implied heavier objects fall faster than lighter ones, aligning with observation (a book falls faster than paper). He argued against the possibility of a vacuum, as motion without resistance implied infinite speed, an absurdity. This rejection also led him to repudiate atomism.

While his physical sciences were fundamental, Aristotle was also a pioneering biologist and taxonomist. He conducted detailed empirical observations, such as studying chick embryo development. Biological change provided his model for understanding all processes: change represented the actualization of potential, like an acorn becoming an oak. He classified animals into bloodless and blooded groups and proposed a hierarchy of souls: nutritive (plants), sensitive (animals), and rational (humans). Though he endorsed spontaneous generation and a gendered reproductive theory (male supplying form, female matter), his biological works were profoundly influential, shaping later thinkers like Galen.

Aristotle's successor at the Lyceum, Theophrastus, extended his work into botany and even critiqued his element theory. Later scholars, like Strato of Lampsacus and the Byzantine John Philoponus, critiqued and refined his mechanics, focusing on acceleration—a phenomenon Aristotle neglected. This began a 2,000-year critical tradition that eventually led to his theories' overthrow. Aristotle's writings became the core of higher learning in late antique, Islamic, and medieval European cultures. His theological elements, like the Unmoved Mover and a hierarchical cosmos, were harmonized with Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, further cementing his authority.

The intellectual legacy of Aristotle fundamentally shaped the trajectory of scientific thought. The clarity and comprehensiveness of his system set the standard for subsequent scientific inquiry. The proximate deaths of Aristotle and Alexander the Great in 322-323 BCE symbolically marked the end of an era and the beginning of a new world, both politically and scientifically, that would be deeply influenced by his monumental achievements.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;