The Hellenistic Era: The Institutionalization of Science and the Roman Technological Paradox

Ancient Greek civilization evolved through two distinct phases: the Hellenic and the Hellenistic. The initial Hellenic period was characterized by independent, agriculturally-supported city-states on the Greek peninsula and in Ionia, operating without a centralized monarchy. A transformative shift began in the fourth century BCE, initiating the Hellenistic phase marked by confederation, imperialism, and conquest. This expansion, spearheaded by Macedonia's King Philip II and his son Alexander the Great, vastly extended Greek cultural and intellectual influence. Alexander's empire, though short-lived (334-323 BCE), stretched from Greece to Egypt, through Mesopotamia, and to the Indus Valley, fundamentally reshaping the ancient world's political and scientific landscape.

The Hellenistic period represents a decisive break in the history of ancient science, transitioning from the solitary natural philosophy of the Hellenic era to a new, cosmopolitan model of state-supported research. This era synthesized Greek theoretical traditions with the bureaucratic, application-oriented science patronized by Eastern kingdoms. The result was a hybridized Hellenistic science—often considered the Golden Age of Greek science—where royal patronage for abstract learning became a novel and enduring feature of organized intellectual life.

The epicenter of this new scientific culture was Ptolemaic Egypt, ruled by a Greek dynasty. Ptolemaios Soter initiated royal patronage, a policy expanded by his successor, Ptolemaios Philadelphus, who founded the legendary Museum at Alexandria. This institution was not a museum in the modern sense but a state-funded research institute—a temple to the Muses dedicated to pure inquiry. For roughly 700 years, the Museum provided stipends, meals, and facilities like lecture halls, a zoo, an observatory, and the famed Library of Alexandria, housing over 500,000 scrolls, to supported scholars.

Patronage motives were multifaceted, blending desires for practical returns with the pursuit of prestige. The Museum supported anatomical research, geography, and possibly military engineering, reflecting applied interests. However, the primary output remained theoretical, with scholars enjoying remarkable freedom from teaching obligations, often viewed as "rare birds" in gilded cages. This institutional model of supporting unfettered research, sustained later by Roman emperors, made Alexandria the preeminent scientific center of the ancient world for centuries.

The Hellenistic support system extended beyond Alexandria. Libraries and museums arose in cities like Pergamum, while in Athens, Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum gained more formal, endowed status under Roman emperors like Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. However, these schools remained primarily teaching institutions, unlike the research-focused Museum. The Alexandrian model facilitated an unprecedented flourish of scientific activity, particularly in the 3rd century BCE, establishing a lasting tradition of formal, abstract mathematics.

Euclid's geometry exemplifies the highly formal, non-arithmetical mathematics developed at Alexandria. Other luminaries included Apollonius of Perga, who mastered conic sections, and Archimedes of Syracuse, antiquity's greatest mathematical genius, who corresponded with Alexandrian scholars. The Library's head, Eratosthenes of Cyrene, famously calculated the Earth's circumference and advanced geography. Pioneering anatomical work by Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Chios, who likely conducted human dissections, also occurred there, alongside significant research in astronomy, optics, and mechanics.

In astronomy, the Eudoxean model of geocentric spheres was challenged. Heraclides of Pontus proposed the Earth's daily rotation, while Aristarchus of Samos postulated a heliocentric cosmology with the Earth revolving around the Sun. Aristarchus's theory was scientifically rejected due to compelling contemporary objections: it violated Aristotelian physics, required an implausibly vast universe to explain the lack of observable stellar parallax, and conflicted with sensory experience. This demonstrates the rational, not dogmatic, grounds for its dismissal.

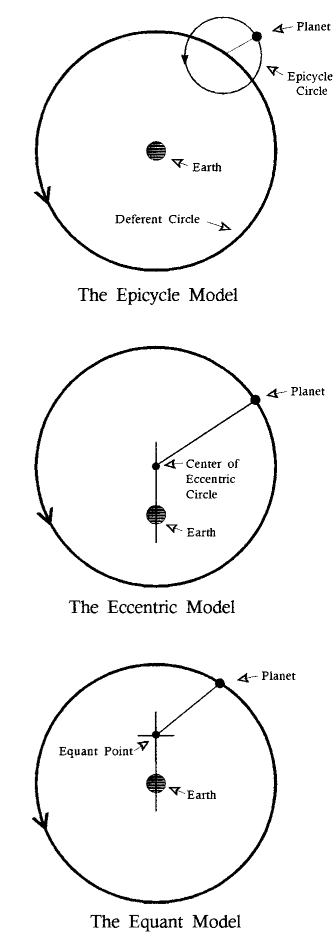

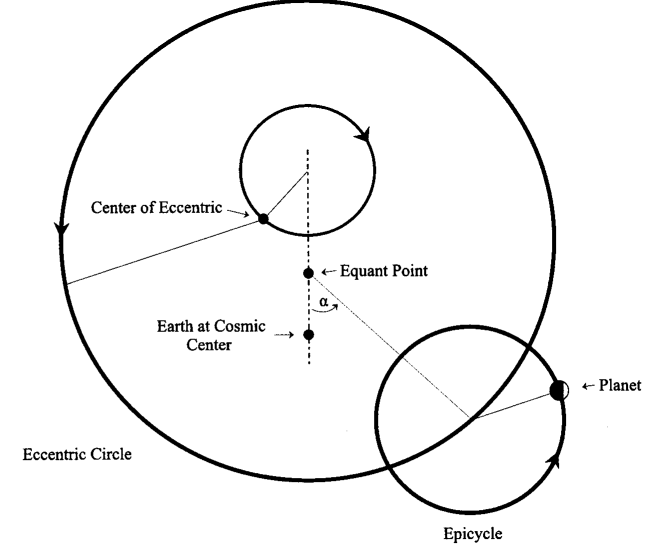

To better "save the phenomena" of planetary motion within a geocentric framework, astronomers developed sophisticated mathematical tools. Apollonius of Perga contributed the concepts of epicycles and eccentrics. This work culminated with Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century CE, whose monumental Almagest (or Mathematical Syntaxis) deployed epicycles, eccentrics, and the equant point to create a highly accurate, though complex, geocentric model that dominated astronomy for 1,500 years.

Fig. 5.1. Ptolemy’s astronomical devices. To reconcile observed planetary positions with the doctrine of uniform circular motion Ptolemy employed epicycles, eccentric circles, and equant points. The epicycle model involves placing circles on circles; eccentrics are off-centered circles; the equant point is an imaginary point in space from which uniform circular motion is measured.

Fig. 5.2. Ptolemy’s model for Mercury. Ptolemy deployed epicycles, eccentrics, and equants in elaborate and often confusing combinations to solve problems of planetary motion. In the case of Mercury (pictured here) the planet rides on an epicycle circle; the center of that circle revolves on a larger eccentric circle, the center of which moves in the opposite direction on an epicycle circle of its own. The required uniformity of the planet’s motion is measured by the angle (a) swept out unvaryingly by a line joining the equant point and the center of the planet’s epicycle circle. These techniques can be made to account for any observed trajectories. The intricate sets of solutions Ptolemy and his successors produced constituted gigantic “Ferris wheel” mechanisms moving the heavens.

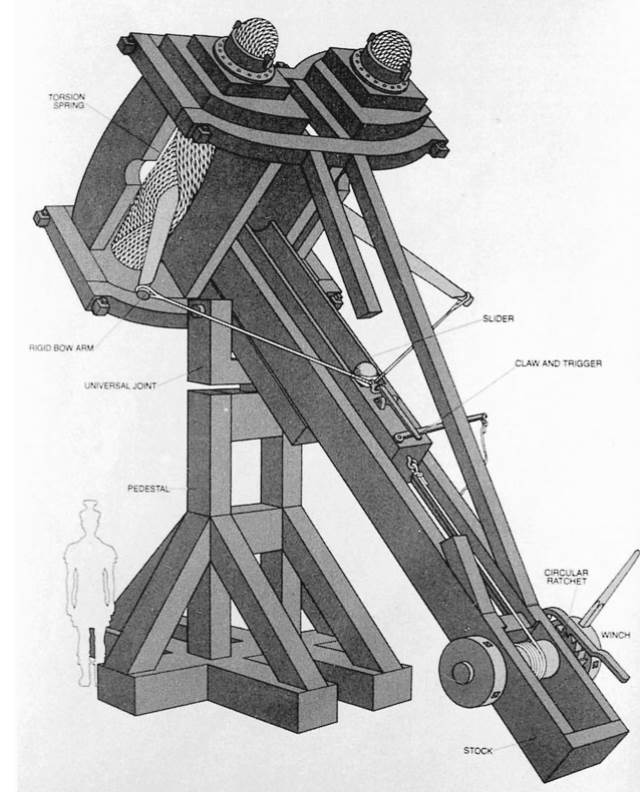

Parallel to astronomy, other fields thrived. A tradition of Hermetic texts and alchemy emerged, combining practical metallurgy with spiritual elements. Theoretical mechanics was advanced by Archimedes, who analyzed simple machines, and by Alexandrian engineers like Ctesibius, Philo, and Hero, who built ingenious automata for wonder rather than utility. While devices like the Archimedean screw had practical use, and state-sponsored research optimized war machines like the torsion-spring catapult, this was largely empirical engineering, not theory-driven applied science.

Fig. 5.3. The torsion-spring catapult. The Greeks under Philip of Macedon had begun to use ballistic artillery in the form of machines that could hurl large projectiles at an enemy. In some designs the action was produced by twisting and suddenly releasing bundles of elastic material. This large Roman model fired stones weighing 70 pounds. Hellenistic scientist-engineers experimented to improve the devices.

Overall, Hellenistic science remained largely detached from technology and production, which existed in a separate, robust domain of craft-based expertise. This separation was reinforced by an ideological disdain for manual labor inherited from earlier Greek thought, maintaining a strict divide between theoria (contemplation) and praxis (action).

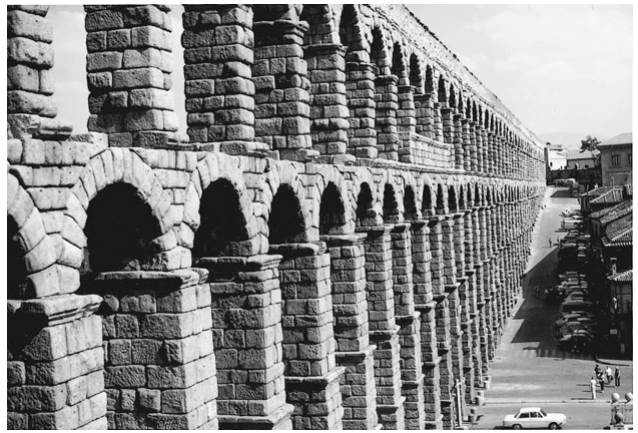

This contrast is starkly illustrated by the Roman Empire, the ancient world's greatest technological civilization, which produced minimal native science. Roman engineering prowess was monumental, evidenced by roads, aqueducts, concrete, and military technology. Recognized engineers like Vitruvius and Frontinus wrote technical treatises. Yet, Rome itself generated no first-rank scientists, largely spurning theoretical Greek learning in favor of practical arts and literary culture.

Fig. 5.4. Roman building technology. Roman engineers were highly competent in the use of the wedge arch in the construction of buildings, bridges, and elevated aqueducts. This Roman aqueduct in Segovia, Spain, is an outstanding example. The invention of cement greatly facilitated Roman building techniques.

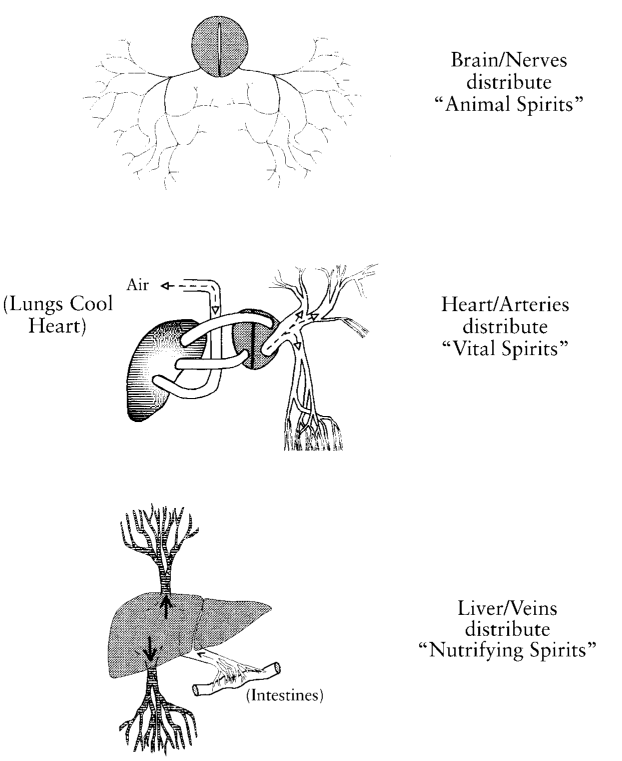

The most notable scientific mind operating in the Roman world was the Greek physician Galen of Pergamum. Building on Hippocratic and Aristotelian traditions, Galen produced a comprehensive, though ultimately erroneous, system of anatomy and physiology. He described three vital systems governed by distinct pneuma (spirits): a nutritive system centered on the liver, a vital system based in the heart and arteries, and a psychic system in the brain and nerves. His voluminous writings became canonical for over a millennium.

Fig. 5.5. Galenic physiology. Ancient physicians and students of anatomy separated the internal organs into three distinct subsystems governed by three different “spirits” functioning in the human body: a psychic essence permeating the brain and the nerves, a vivifying arterial spirit arising in the heart, and a nutrifying venous spirit originating in the liver.

In conclusion, the Hellenistic period institutionalized science through state patronage, enabling towering theoretical achievements with limited practical application. The subsequent Roman Empire demonstrated that advanced technological civilization could flourish almost entirely independent of the concurrent tradition of theoretical natural philosophy, highlighting the long-standing historical separation between science and technology in the ancient world.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;