Imperial China: Geography, Governance, and Scientific Legacy in Historical Context

Although its political borders experienced fluctuations, the realm controlled by successive Chinese emperors constituted a vast, densely populated territory comparable in size to Europe. Excluding peripheral regions such as Manchuria and Tibet, China proper alone encompassed half of Europe's landmass, remaining seven times larger than France. Following its initial political unification in 221 BCE under the Qin Dynasty, China consistently ranked as the world's most populous nation. With a population in China proper reaching an estimated 115 million by 1200 CE, it doubled the demographic weight of contemporary Europe and sustained a population density nearly five times greater. This demographic and political scale established imperial China as a preeminent entity in the pre-modern world.

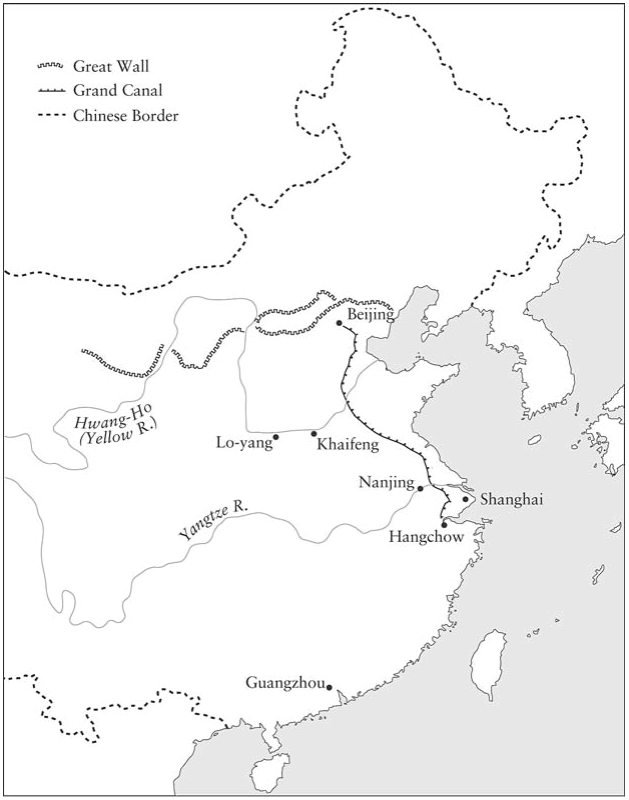

Geographical factors profoundly shaped China's historical trajectory, isolating it from other Old World civilizations to a significant degree. While nomadic peoples of the northern steppes persistently influenced Chinese history, formidable natural barriers—including the Himalayas, the Taklamakan Desert, and the Central Asian steppes—ringed its southwestern, western, and northern frontiers. These barriers impeded sustained contact with cultural developments in West Asia and Europe. Chinese civilization originated as a hydraulic civilization in the Yellow River (Hwang-Ho) valley during the second millennium BCE, later expanding to the Yangtze River basin. This eastward-facing cultural orientation was fundamentally tied to these major river systems and their associated agricultural regimes.

Map 7.1. China. This map illustrates the geographical foundations of Chinese civilization, which originated along the Hwang-Ho (Yellow) River. The surrounding mountains, deserts, and steppes in the north and west created relative isolation from the rest of Asia. The first unification in the third century BCE established the largest political entity of its time. The map also details two monumental engineering achievements: the Great Wall, built for defense, and the Grand Canal, constructed for transportation and economic integration.

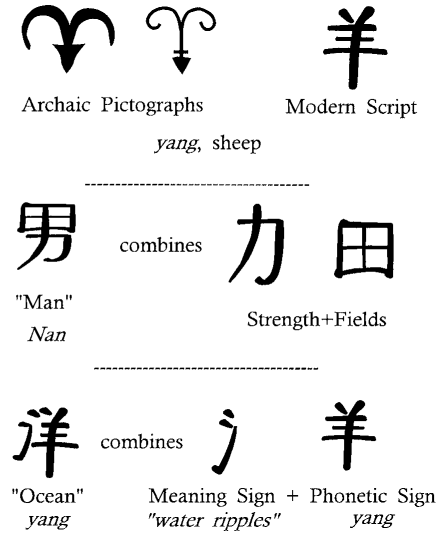

The development of writing in China followed an independent path, resulting in a complex, ideographic script. Early evidence appears in the oracle bone script of the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE), which utilized hundreds of basic signs. By the time of unification, these characters had become standardized into a system where components were combined to create tens of thousands of distinct characters. Unlike ancient Egyptian or Sumerian writing, which simplified toward phonetic systems, Chinese retained its logographic nature, with each character embodying both phonetic and semantic elements. This complexity made literacy difficult to master, yet it did not prevent the emergence of a long and unbroken literary and scientific tradition from antiquity onward.

China's history is marked by remarkable cultural continuity across millennia, despite the cyclical rise and fall of imperial dynasties. The Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE) represents a pinnacle in this long narrative, often termed a Chinese "renaissance." This era is widely regarded as the zenith of traditional Chinese science and technology, providing a crucial benchmark for global comparison. The Song's flourishing was underpinned by an agricultural transformation, particularly the surge in rice cultivation in the Yangtze basin. The introduction of fast-ripening, drought-resistant Champa rice varieties from Indochina after 1012 CE enabled two or three harvests annually, revolutionizing food production.

Agricultural innovation under the Song was state-directed and intensive, involving land reclamation, terracing, and advanced irrigation projects. The adoption of new techniques, such as transplanting rice seedlings and employing specialized tools like the rice-field plow and paddle-chain water wheel, dramatically boosted productivity. The consequences were transformative: China's population more than doubled between 800 and 1200 CE, the demographic and economic center shifted decisively southward, and urbanization accelerated rapidly. Song China featured several cities with populations exceeding one million, with an estimated urban population reaching 20%—a level of urbanization not achieved in Europe until the industrial era.

Political power during the Song became increasingly centralized under the emperor, administered by a vast scholarly bureaucracy known as the mandarinate. The state ideology of the "Mandate of Heaven" legitimized imperial rule, while a refined civil service examination system created a pervasive meritocratic administration. This bureaucracy was immense and monolithic, exerting direct control to the village level without countervailing independent institutions, such as autonomous cities, powerful guilds, or independent universities. This centralized structure effectively co-opted intellectual talent and limited the development of scientific inquiry outside official channels.

Fig. 7.1. Chinese pictographic writing. This figure demonstrates the pictographic origins and combinatorial nature of written Chinese. Characters often incorporate elements that suggest sound (phonetic components) and meaning (semantic radicals). Despite its complexity, requiring mastery of thousands of characters, the system supported the development of sophisticated technical and scientific lexicons, preserving a continuous written tradition for millennia.

The philosophical framework of Confucianism, particularly the Neo-Confucianism systematized during the Song, dominated elite culture. This practical philosophy emphasized ethics, statecraft, filial piety, and social harmony over the investigation of the natural world. It reinforced a paternalistic social order and a scholarly focus on the humanities. The civil service exams, perfected under the Song, were the primary gateway to status and power, demanding exhaustive mastery of Confucian classics, poetry, and calligraphy. While creating a stable, meritocratic governing class, this system overwhelmingly directed intellectual energy toward humanistic and administrative studies, with science and technology largely excluded from the formal curriculum.

Other social groups lacked the autonomy to foster alternative scientific traditions. The military, though large, was kept under strict civilian control. The merchant class, viewed with suspicion within the Confucian value system that disdained profit-seeking, was systematically regulated and prevented from achieving independent social or political influence. Furthermore, a major suppression of Buddhist institutions in the 9th century eliminated the clergy as a potential rival to the bureaucratic state. Consequently, with talent funneled into the mandarinate, and with no other powerful, autonomous social entities to support it, a sustained, institutionalized scientific revolution independent of state purposes failed to emerge from China's otherwise unparalleled technological sophistication.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;