The Social History of Science in Traditional China: State Patronage and Utilitarian Knowledge

A balanced approach to the natural sciences in traditional China must avoid undue emphasis on seeking "first" honors in discovery, such as early fossil recognition or alleged anticipations of modern wave theory. Such claims often reflect a problematic judgmentalism that inflates Chinese accomplishments while devaluing Western ones. Instead, a more fruitful analysis emphasizes the social history of Chinese science, examining how it supported statecraft. This perspective reveals that China's relationship between science and society paralleled other Old World civilizations, where useful knowledge was developed under state patronage.

Evaluating Chinese science faces significant conceptual obstacles. The Western concept of natural philosophy as a unified critical inquiry into nature remained foreign. As noted, "China had sciences, but no science." Experts pursued activities in astronomy, mathematics, medicine, and alchemy, but these were not integrated into a single enterprise. Crucially, no social role existed for the research scientist; instead, elite amateurs and polymaths pursued scientific interests within a bureaucratic context, often while applying useful knowledge.

The traditional Chinese worldview was holistic and organismic. Emerging by the Han Dynasty, it conceived the universe as a single organism where nature and humanity merged into unity. This qualitative outlook was governed by the complementary forces of yin and yang and the dynamic Five Phases (metal, wood, water, fire, earth). Change was seen in terms of recurring cycles where these elements predominated. This fundamental philosophical framework created an intellectual world distinct from the West, shaping all scientific thought.

Institutions also presented barriers. Despite a complex educational structure topped by an Imperial Academy, instruction focused solely on a standardized Confucian curriculum for civil service exams. No school possessed a charter granting permanent independence, and all could be closed by imperial decree. While separate schools for law, medicine, and mathematics were briefly established around 1100 CE, none endured. Consequently, the sciences found no formal place in Chinese educational institutions, contrasting sharply with the autonomous universities developing in Europe.

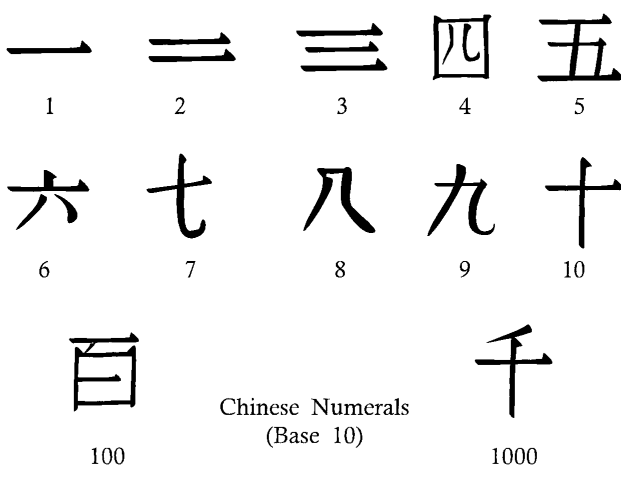

Despite these impediments, imperial administration necessitated developing useful knowledge. Applied mathematics became essential to statecraft. By the fourth century BCE, a decimal place-value number system was developed, facilitated by counting rods and the abacus. Chinese mathematicians mastered arithmetic operations, squares, cubes, and techniques for what are now quadratic equations. By the thirteenth century CE, they were among the world's greatest algebraists.

However, the thrust of Chinese mathematics was overwhelmingly practical. The foundational text Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art presented 246 problem-solutions on land measurement, exchange rates, and distribution. Chinese mathematicians used sophisticated algebraic techniques but never developed a formal geometry or deductive proof system like Euclid. The social structure further fragmented the discipline; mathematicians were scattered minor officials, and expertise was often kept secret or passed down within families, disrupting intellectual continuity.

Fig. 7.4. Chinese numerals (base 10). Chinese civilization developed a decimal, place-value number system early in its history. Supplemented with calculating devices such as the abacus, the Chinese number system proved a flexible tool for reckoning the complex accounts of Chinese civilization.

State support for useful knowledge is epitomized by Chinese astronomy. Issuing the calendar was an imperial prerogative, critical for legitimizing rule. Like Mesopotamian counterparts, Chinese calendar-keepers maintained accurate lunar and solar calendars, synchronizing them using the Metonic cycle. Astronomical observation became a state secret early on, managed by an Imperial Bureau of Astronomy. Personnel were often hereditary, and rules prohibited their children from other careers, ensuring controlled expertise.

Chinese cosmology often featured a stationary earth within a celestial sphere divided into twenty-eight lunar mansions. The emperor, as the Son of Heaven, was the linchpin connecting heaven and earth. While theoretical models were not emphasized, astronomers became acute observers. Records from as early as the eighth century BCE show impressive achievements: measuring the solar year at 365.25 days, systematic star catalogs, and meticulous logs of eclipses, novae, sunspots, and comets, including Halley's Comet sightings from 240 BCE.

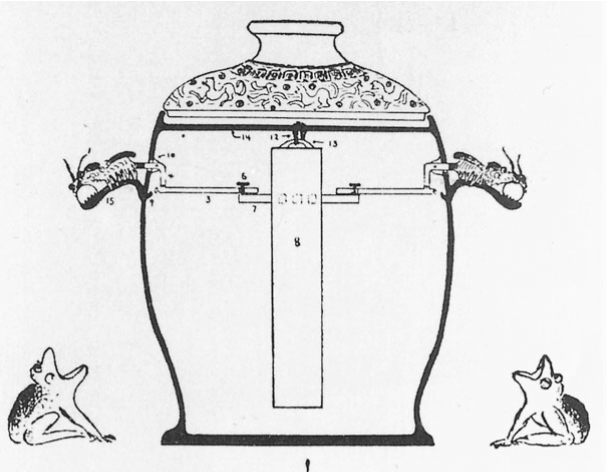

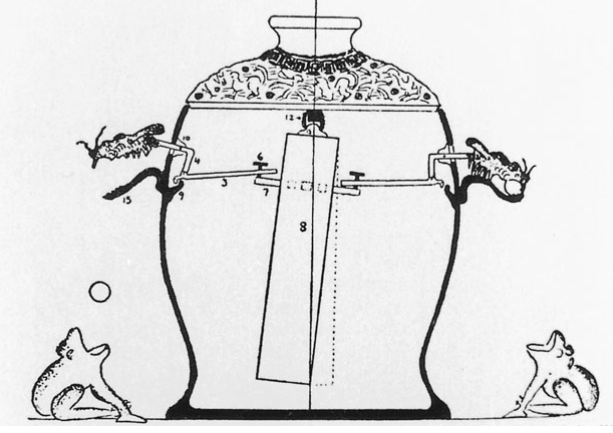

The state also systematically collected weather data, compiled tide tables, and studied meteorites for practical administrative purposes. Furthermore, the threat of earthquakes prompted state-sponsored study. In the second century CE, Zhang Heng invented an ingenious seismograph, or "earthquake weathercock," to detect distant tremors, representing a practical application of engineering for state welfare.

Fig. 7.6. Chinese seismograph. Earthquakes regularly affected China, and the centralized state was responsible for providing relief for earthquake damage. As early as the second century BCE, Chinese experts developed the device depicted here. An earthquake would jostle a suspended weight inside a large bronze jar, releasing one of a number of balls and indicating the direction of the quake.

Cartography flourished under state needs for administration and expansion. Chinese map-makers created highly accurate maps using grid systems and produced relief maps. Notably, they employed projections akin to the Mercator projection centuries before its Western namesake. Under the Northern Song, a distance-measuring wagon was designed, and later Ming cartographers produced atlases following maritime expeditions.

State regulation extended to medicine, viewed as a public service. An Imperial Medical College existed by the Tang Dynasty, and physicians underwent state examinations. The government issued official pharmacopoeias; the monumental Pen Tsao Kang Mu compiled by Li Shizhen listed 1,892 medicaments. The focus on practical applications is also seen in detailed natural histories, particularly concerning the silkworm, vital to the state economy.

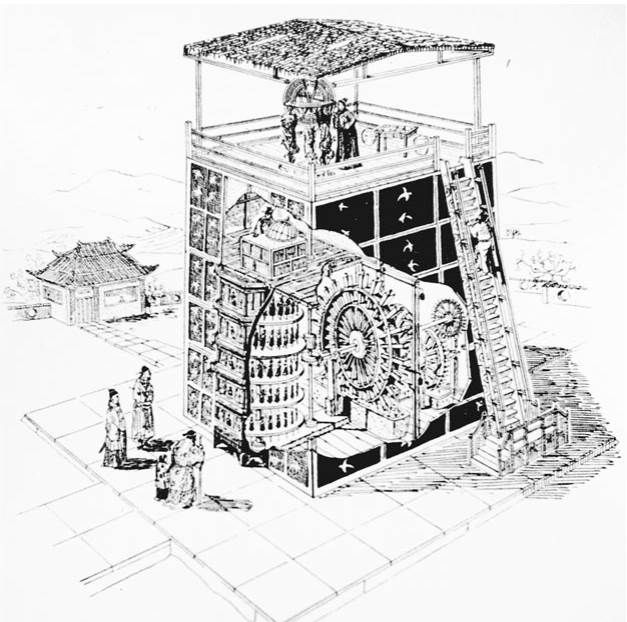

A significant technological achievement was in horology. Around 725 CE, artisan Liang Lingzan invented the mechanical escapement. This reached its zenith with Su Song's monumental astronomical clock-tower built in 1090 CE. This water-powered device featured an armillary sphere and celestial globe.

Fig. 7.5. Su Sung’s astronomical clock. Built in 1090 Su Sung’s clock was an impressive feat of mechanical engineering and the most complex piece of clockwork to that point in history. Housed within a 40-foot-high tower, powered by a waterwheel, and controlled by complicated gearing, Su Sung’s machine counted out the hours and turned a bronze armillary sphere and a celestial globe in synchrony with the heavens.

However, expertise in such complex machinery declined after the Song Dynasty, exemplifying a pattern of lost knowledge. Furthermore, alchemy and occult sciences, closely tied to Taoist philosophy, were prominent. Chinese alchemists sought elixirs of immortality and spiritual transcendence, with their experiments inadvertently leading to inventions like gunpowder.

Chinese science experienced three major waves of foreign influence. The first (600-750 CE) involved Buddhist and Indian sciences during the Tang. The second wave came with the Mongol conquest, introducing Islamic astronomy and instruments, though core Greek texts like Euclid's were not assimilated. A period of rigidity followed during the Ming Dynasty, turning China inward.

The third wave arrived with Europeans, notably the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci in 1582. While his religion was resisted, his Western astronomy, mathematics, and calendrical science were valued for their superior accuracy and utility. Ricci and later Jesuits gained control of the Astronomical Bureau, not with heliocentric theory but with refined Ptolemaic models. Their success underscored the Chinese measure of value: practical utility for the state. With this encounter, Chinese science began its integration into the ecumenical tradition of world science.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;