The Byzantine Empire: Preserving and Institutionalizing Science in the Eastern Mediterranean

The fall of Rome in 476 CE precipitated the transformation of the empire's eastern provinces into the Byzantine Empire, a Greek-speaking Christian state centered on Constantinople. Governed by a complex imperial bureaucracy, this civilization endured for a millennium until the Ottoman Turks conquered its capital in 1453. Initially flourishing with resources like the Egyptian breadbasket, wealthy emperors sustained numerous traditional institutions of higher learning, creating a unique environment for scientific endeavor.

While often criticized as anti-intellectual and stifled by mystical state religion, exemplified by Emperor Justinian's closure of Plato's Academy in Athens in 529 CE, Byzantine science merits deeper historical study. Dismissing it overlooks significant continuations of Hellenistic traditions and the institutionalization of useful knowledge, characteristic of eastern bureaucratic civilizations. State and church schools continued to teach the mathematical sciences, or quadrivium—arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music—alongside the physical sciences and medicine, with libraries serving as vital centers for this scholarship.

A paramount Byzantine innovation was the true hospital, an institution for in-patient medical treatment rooted in Christian mercy. Functioning primarily as a center for medical technology, these establishments, funded by government, church, and aristocracy, also became hubs for medical research. Byzantine medicine fully assimilated the teachings of Galen and Hippocrates, with some hospitals maintaining libraries, teaching programs, and fostering original investigations. Additionally, veterinary medicine was a notably supported field due to the strategic importance of cavalry, resulting in sophisticated veterinary manuals.

In the exact sciences, Byzantine scholars directly inherited and engaged with Greek learning, including the works of Aristotle, Euclid, and Ptolemy. Astronomers and mathematicians produced sophisticated treatises using earlier Greek and contemporary Persian sources, though their work often included a strong element of astrology. Similarly, scholars pursued mathematical music theory, likely for liturgical purposes, while Byzantine alchemy and alchemical mineralogy represented significant areas of both research and perceived practical utility.

The preeminent natural philosopher of the early Byzantine era was John Philoponus, who worked in sixth-century Alexandria. He launched the most comprehensive critique of Aristotelian physics before the European Scientific Revolution. In his ingenious analysis of projectile motion—which Aristotle poorly explained—Philoponus proposed the projector imparted an internal motive force to the object. His focused critiques later proved profoundly influential among Islamic and European natural philosophers re-examining Aristotle's work.

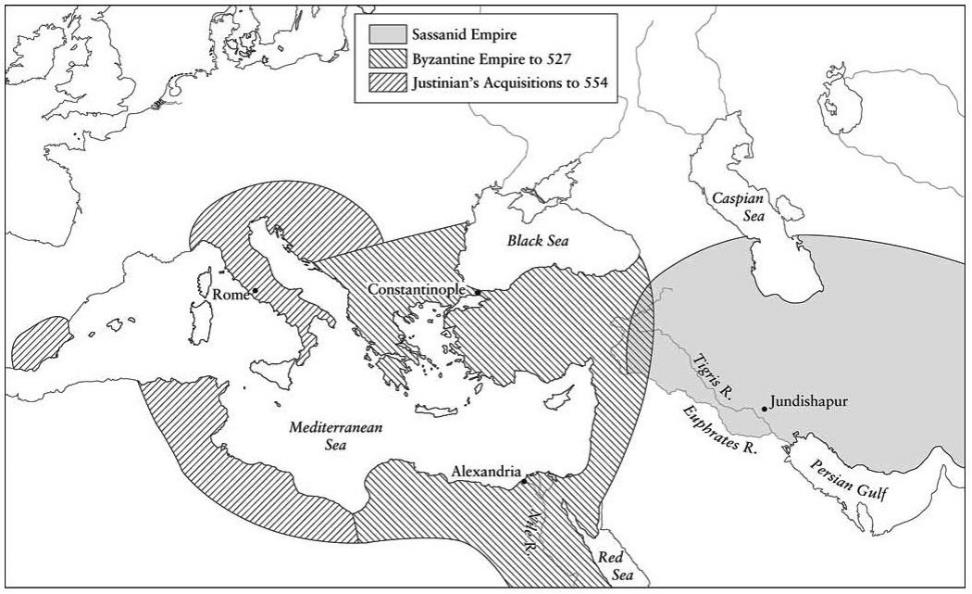

Map 6.1: Byzantium and Sassanid Persia. In late antiquity two derivative civilizations took root in the Middle East—the Byzantine Empire centered in Constantinople and Sassanid Persia in the heartland of ancient Mesopotamia. Both assimilated ancient Greek science and became centers of learning.

A full social history of Byzantine science would present the subject more favorably than an intellectual history focused solely on theoretical originality. This perspective values practical manuals on medicine, veterinary science, agriculture (farmers’ manuals and herbals), astrology, and alchemy. In an extremely centralized bureaucracy, support flowed to encyclopedists, translators, and writers of manuals on useful, mundane subjects—precisely the work often neglected by historians seeking theoretical novelty.

The seventh-century loss of Egypt and the Nile Valley to Arab invasions severely damaged the Byzantine economy and society. Nevertheless, a reduced Byzantium maintained its urban centers, institutions, and scientific activities for centuries. Inevitable decline accelerated after 1000 CE amid pressures from Turks, Venetians, and European Crusaders. The catastrophic sack of Constantinople by Crusaders in 1204 was a death knell, culminating in the city's final fall to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. Although not a font of radically original science, the Byzantine Empire crucially preserved the tradition of secular Greek learning alongside its official Christianity, ensuring its transmission to later cultures.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;