The Development and Characteristics of Pre-Columbian North American Civilizations

In contrast to the centralized empires of Mesoamerica and South America, pre-Columbian North America did not give rise to a singular, continent-spanning high civilization. This divergence is largely attributed to geography and ecology. The eastern two-thirds of the continent featured vast forests and plains drained by great rivers, an environment that supported lower population densities which never crossed the critical thresholds necessary for bureaucratic state formation. Initially, a Paleolithic economy of hunting and gathering was universal. In some regions, an intensified Archaic period developed, involving systematic exploitation of deer, fowl, wild grains, and nuts. A fundamental transition began around 500 BCE with the introduction of Neolithic agriculture, specifically the cultivation of corn, beans, and squash from Central America. This shift enabled more complex social organizations.

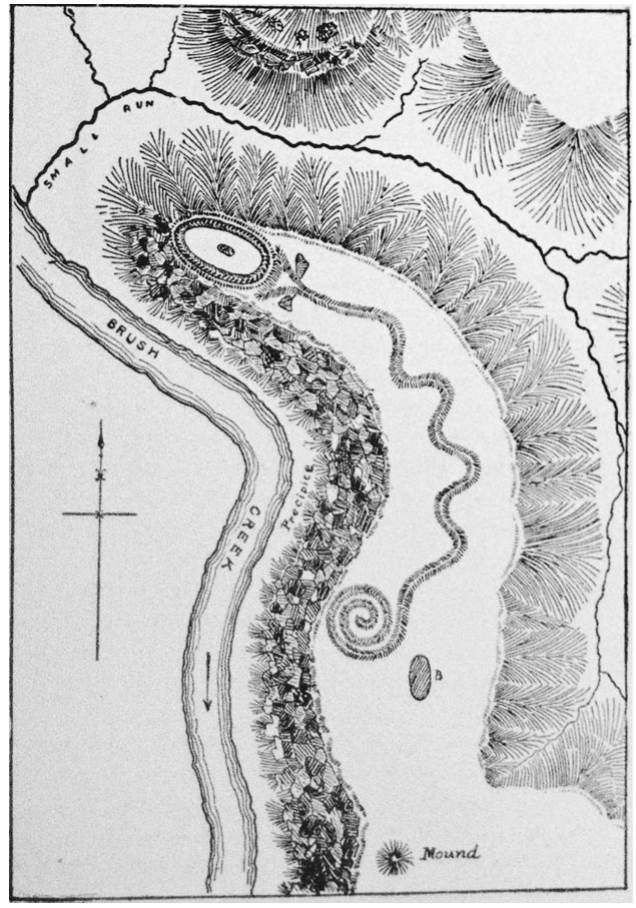

The increased wealth and food security of the Neolithic era fostered more stratified societies, permanent settlements, and extensive trade networks. These cultures, collectively known as the Mound Builders, such as the Adena (c. 1000–200 BCE) and Hopewell (c. 200 BCE–500 CE) traditions, are defined by their large-scale earthen constructions. These mounds served as mortuary sites, ceremonial centers, and possibly redistribution hubs for goods. A premier example is the Great Serpent Mound in Ohio, a quarter-mile-long effigy. The social complexity reflected in these coordinated building projects is strongly reminiscent of Neolithic sites like Stonehenge, indicating sophisticated astronomical and community knowledge.

Fig. 9.7. Great Serpent Mound. Like Neolithic societies elsewhere, Native American groups constructed substantial, often astronomically aligned structures. This early illustration depicts the Great Serpent Mound (Adams County, Ohio), likely built by the Adena culture between 100 BCE and 700 CE. The four-foot-high earthwork, perched on a bluff, uncoils for a quarter-mile, depicting a snake ingesting an egg. It likely functioned as a regional ceremonial and trade center for multiple groups.

The cultural evolution in North America thus paralleled global patterns: successive Paleolithic, Archaic, Neolithic, and intensified Neolithic stages. Each stage developed corresponding technologies and knowledge systems to sustain populations. Amerindian groups independently created practical astronomies, as evidenced by solstice-aligned mounds, astronomical petroglyphs possibly recording the Crab Nebula supernova of 1054, and the "medicine wheels" of the Plains Indians. These artifacts represent diverse but familiar responses to the natural world by hunter-gatherers and early farmers.

A significant cultural zenith was reached with the Mississippian culture, which flourished from approximately 750 to 1600 CE in the American Midwest. Based on intensive maize agriculture, it achieved unprecedented social complexity for the region. The Mississippians established the first true city in North America, Cahokia, located in modern Illinois. At its peak around 1200 CE, Cahokia covered six square miles, featured hundreds of platform mounds and temples, and sustained a population of 30,000–40,000, functioning as a major political and religious center.

In the arid Southwest, a distinct social development occurred, illustrating a revealing interplay of ecology, technology, and social organization. Groups like the Hohokam and Anasazi (or Ancestral Puebloan Peoples) achieved an intermediate level of development between Neolithic societies and full-blown civilizations through managed irrigation, creating what can be termed an "incipient hydraulic society." This condition produced intermediate levels of political centralization, social stratification, monumental architecture, and scientific development, offering a clear case study of factors driving early civilization.

The Hohokam migrated from Mexico to Arizona around 300 BCE, bringing advanced irrigation technology. By 800 CE, their engineers had constructed a vast canal system tapping the Gila River, with main canals extending for kilometers. This system irrigated an estimated 30,000 acres, enabling two annual crops. The agricultural surplus spurred population growth, political centralization, and territorial expansion, demonstrating the direct social repercussions of technological control over water.

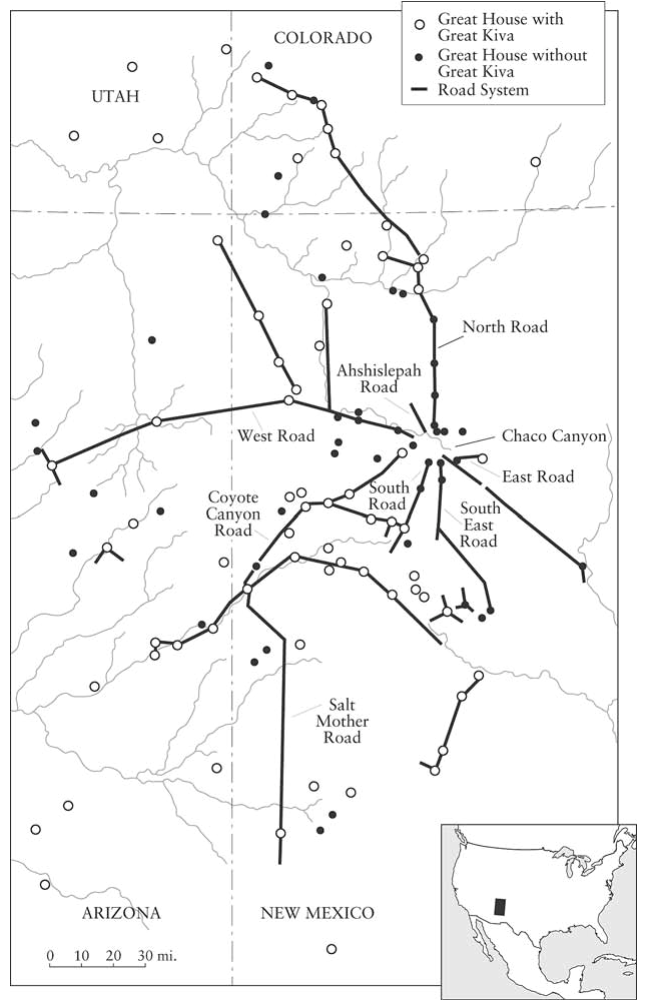

Map 9.3. Civilization in the American Southwest. Around 1,500 years ago, complex societies formed north of Mexico. The Anasazi flourished around 1050 CE. Regional agricultural intensification through irrigation supported dispersed population centers connected by an extensive road network.

To the north, the Anasazi culture coalesced around 700 CE, reaching its peak from 950 to 1150 CE in the Four Corners region. In this barren desert with only nine inches of annual rain, they engineered a thriving society. Their achievements included distinctive cliff dwellings, an 800-unit great house at Chaco Canyon requiring timber transported from 80 kilometers away, and a regional road network up to nine meters wide. Agricultural production at modern yield levels was made possible by sophisticated irrigation works tapping the San Juan River Basin, using canals, check dams, and terraces. Their settlement pattern—dispersing 75 communities over 25,000 square miles—likely served as a risk-management strategy against localized crop failure.

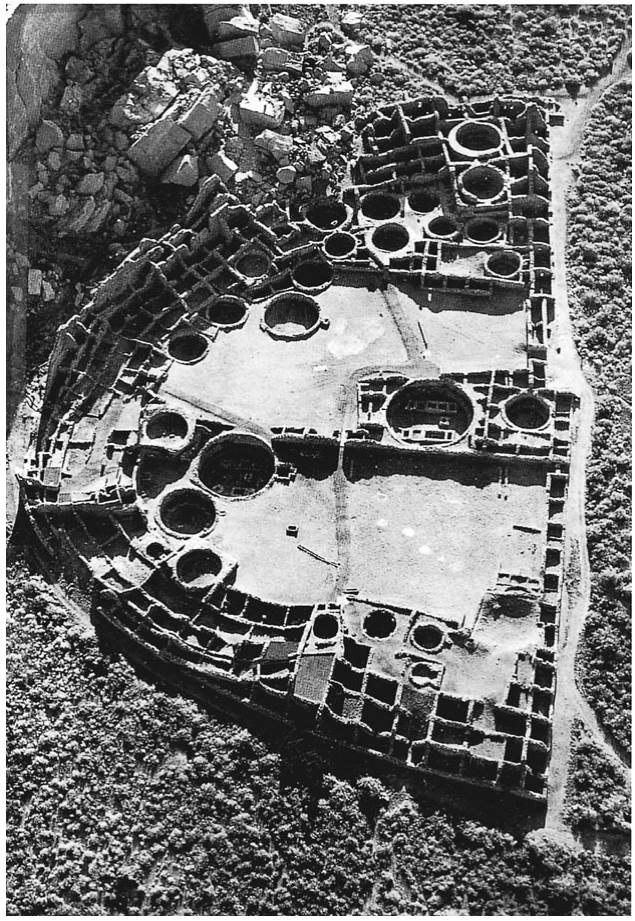

Anasazi scientific expertise is vividly demonstrated in their astronomy. A pivotal discovery in 1977 was the "Sun Dagger" observatory on Fajada Butte in Chaco Canyon. This precise rock alignment marks the summer and winter solstices, the spring and fall equinoxes via light beams striking a spiral petroglyph, uniquely tracking the sun at its zenith. It also records the 18.6-year lunar cycle. Furthermore, their ceremonial kivas were astronomically aligned; the Great Kiva at Pueblo Bonito was circular to mirror the heavens, with its door aligned to the North Star and solstitial sunlight illuminating a special niche.

Fig. 9.8. The Great Kiva at Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon. The Anasazi settled in the Southwest in the eighth century CE. Their society flourished through advanced water management. They built cliff dwellings and large ceremonial kivas, which served as storage and ritual centers. These constructions, including the Great Kiva, embody significant astronomical knowledge aligned with celestial events.

Ultimately, the ecological constraints of the desert Southwest limited the scale of Anasazi development compared to Old World hydraulic civilizations. Their population density, political centralization, and monumental building, while impressive, remained at an intermediate level. Nevertheless, their clear trajectory toward greater complexity underscores the universal association between agricultural intensification, social stratification, and the development of systematic knowledge like astronomy. The collapse of Anasazi society after the severe drought of 1276–1299 CE highlights the precarious balance and marginal viability of even the most ingenious civilizations in environmentally challenging settings.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;