The Medieval Agricultural Revolution: Technological Innovation and Social Transformation in Medieval Europe

The Medieval Agricultural Revolution constituted a direct response to profound demographic and ecological pressures in medieval Europe. Between 600 and 1000 CE, the continent's population surged by approximately 38 percent, with regions like France experiencing growth nearing 45 percent. This population increase occurred alongside competing land uses: cropland for food and fiber, pasture for animals, expanding cities, and forests vital for timber, fuel, and iron production. By the ninth century, these strains created an ecological crisis reminiscent of earlier Neolithic challenges, compelling European societies to intensify agricultural production, though through different means than ancient irrigation-based civilizations.

Europe's path to agricultural intensification diverged from the ancient East due to its distinct ecological conditions. Sufficient natural rainfall precluded a reliance on large-scale irrigation. Instead, increasing output required cultivating the heavy, fertile soils of Northern Europe, which resisted the shallow Mediterranean scratch plow. The solution emerged as a unique constellation of technological innovations adapted specifically to this northern environment, collectively driving the European Agricultural Revolution and fundamentally reshaping society.

A primary innovation was the widespread adoption of the heavy plow. This wheeled implement, constructed from wood and iron and armed with a cutter, tore soil at the root line and turned it over into a furrow, eliminating the need for cross-plowing. While the Roman-invented tool was rarely used in antiquity, it became crucial for farming Europe's wet lowlands. However, its immense friction required a team of up to eight oxen, making it a capital-intensive technology that fostered collective ownership and communal agriculture.

A second critical advancement was the substitution of the horse for the ox as the primary draft animal. This shift leveraged the horse's superior speed and endurance but required adapting the horse collar, a technology derived from Chinese innovation centuries prior. This device transferred pressure from the animal's windpipe to its shoulders, increasing traction four- to fivefold. Coupled with the iron horseshoe, a European innovation, it enabled a more efficient and powerful agricultural and transport system.

The three-field rotation system completed the core technological triad. It replaced the Mediterranean two-field system, where one field lay fallow each year. Under the new pattern, arable land was divided into three sections: one planted with a winter crop like wheat, a second with a spring crop of oats, peas, beans, or barley, and a third left fallow in rotation. This system significantly improved peasant diets through diverse spring plantings and boosted the land's productive capacity from roughly 33 to 50 percent.

These innovations yielded profound social consequences. The heavy plow enabled settlement and farming of the rich alluvial soils of the Northern European plain, shifting Europe's agricultural center northward. Its high cost also solidified communal animal husbandry and the medieval village, reinforcing the manorial system as the bedrock of European society. The collective investment in technology cemented village structures that persisted for centuries.

Similarly, the shift to horse power expanded the economic "radius" of villages, facilitating larger, more socially diverse settlements and decreasing transport costs. This enhanced connectivity allowed more villages to integrate into regional and long-distance trade networks. Concurrently, the three-field system generated an extraordinary surplus of food production, which directly fueled urbanization, the growth of European cities in the High Middle Ages, and supported non-agricultural sectors.

A richer, more urbanized Europe emerged, destined to lead in technological progress but also containing seeds of future crises: land shortage, timber famine, further population pressure, and eventual global ecological disruption. By 1300, Europe's population had trebled to 79 million. Cities like Paris grew tenfold, coinciding with a wave of cathedral building, university founding, and the flourishing of high medieval culture, all underpinned by agricultural surplus.

Agriculture was not the sole domain of transformative technology. In military affairs, the adoption of the stirrup—invented in China and diffused westward—was pivotal. This deceptively simple device stabilized a warrior on horseback, enabling "mounted shock combat." A rider with a lance could now function as a formidable unit where momentum replaced muscle, giving rise to the definitive figure of European feudalism: the armored knight.

This new military technology meshed seamlessly with the manorial system. The knight, whose equipment was financially manageable for a local lord, became a full-time warrior, replacing peasant-soldiers. This fostered feudal relations where vassal knights pledged loyalty in exchange for governance rights. The system suited Europe's decentralized political landscape, requiring no strong central bureaucracy. The village, transformed by the Agricultural Revolution, now produced the surplus needed to support the knightly class, which in turn provided local policing, justice, and defense.

The custom of primogeniture, whereby feudal lands passed to the firstborn son, created a growing class of landless knights. This pressure contributed to the eruption of the Crusades, a first wave of European expansion beginning in 1096. These expeditions, lasting nearly 200 years, saw European invaders confront the technologically equal and culturally superior Byzantine and Islamic civilizations.

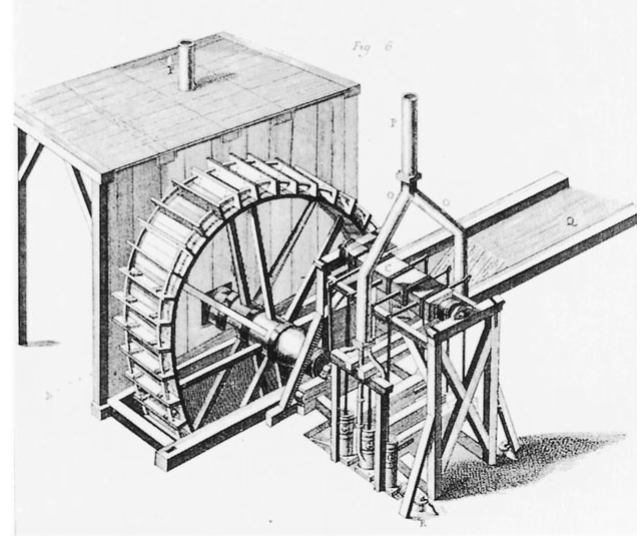

Coincident with these changes, medieval Europe developed a pronounced fascination with machines and non-human power, becoming the first major civilization not primarily dependent on human muscle power. The waterwheel was widely adopted to harness Europe's abundant streams, powering sawmills, flour mills, and hammer mills. Windmills appeared, sometimes reclaiming land from the sea. This shift to labor-saving machines is linked to a lack of surplus labor and the increased grain production from the agricultural boom, and it coincided with the withering of slavery in Western Europe.

Fig. 10.1. Water power. Europeans began to use wind and water power on an unprecedented scale. Undershot waterwheels were constructed at many sites along the profuse streams with which Europe is favored.

Anonymous medieval engineers also mastered mechanical gearing and linkage, using wind for windmills and tidal flow for tidal mills. They perfected devices like the spring catapult (trebuchet), tapping into more non-human energy than any contemporary world region. This "power-conscious" culture fostered a distinctive attitude of viewing nature as a wellspring of power to be exploited technologically—an outlook with enduring and consequential legacy.

The impressive array of technological innovations that transformed medieval Europe owed little to theoretical science, which had limited practical applicability at the time. Useful knowledge was largely pragmatic, involving geometry for surveying and calendrical reckoning. However, the civilization these technologies built created new conditions for intellectual life. During the "Renaissance of the twelfth century," European scholars engaged with scientific traditions from antiquity and Islam. Uniquely, Europe institutionalized higher learning in the university, setting the stage for future scientific revolutions. Thus, the Medieval Agricultural Revolution was not merely a series of farming improvements but a foundational event that reshaped Europe's ecological, social, military, and intellectual trajectory.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;