The Scientific Revolution in Europe: Social, Technological, and Intellectual Contexts of the 16th-17th Centuries

The social context for science in Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, known as the Scientific Revolution, changed dramatically from the Middle Ages due to several pivotal developments. The Military Revolution, European voyages of exploration, and the discovery of the New World fundamentally altered the intellectual landscape. These events undermined the closed Eurocentric cosmos of medieval thought, while the empirical science of geography provided a direct stimulus. The emphasis on observational reports and practical experience from new discoveries challenged received authority, making cartography an exemplary new methodology superior to relying on inherited dogma. Consequently, many key figures of the Scientific Revolution were intimately involved in geographical or cartographic pursuits.

A pivotal technological shift occurred with Johannes Gutenberg's invention of printing with movable type in the late 1430s, which spread rapidly after 1450. This innovation created a "communications revolution" that increased the volume and accuracy of information, rendering scribal copying obsolete. By 1500, roughly 13,000 works had been printed, breaking the university monopoly on learning and fostering a new lay intelligentsia. Print shops themselves became intellectual centers where authors and publishers collaborated. The Renaissance humanism movement, emphasizing classical texts, was sustained by printing, which also enabled the recovery of ancient Greek scientific works like those of Archimedes from original sources rather than Arabic translations.

The cultural flourishing of the Renaissance, particularly in Italy, represented another crucial changed condition. This urban, secular phenomenon, aligned with court patronage, produced artistic giants like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. A defining technical advance was the use of perspective—a mathematical projection system for rendering three-dimensional space realistically on a two-dimensional surface, advanced by figures like Leon Battista Alberti. This artistic demand for accuracy drove a parallel explosion in anatomical research, placing Renaissance artists and anatomists at the vanguard of uncovering new knowledge about nature.

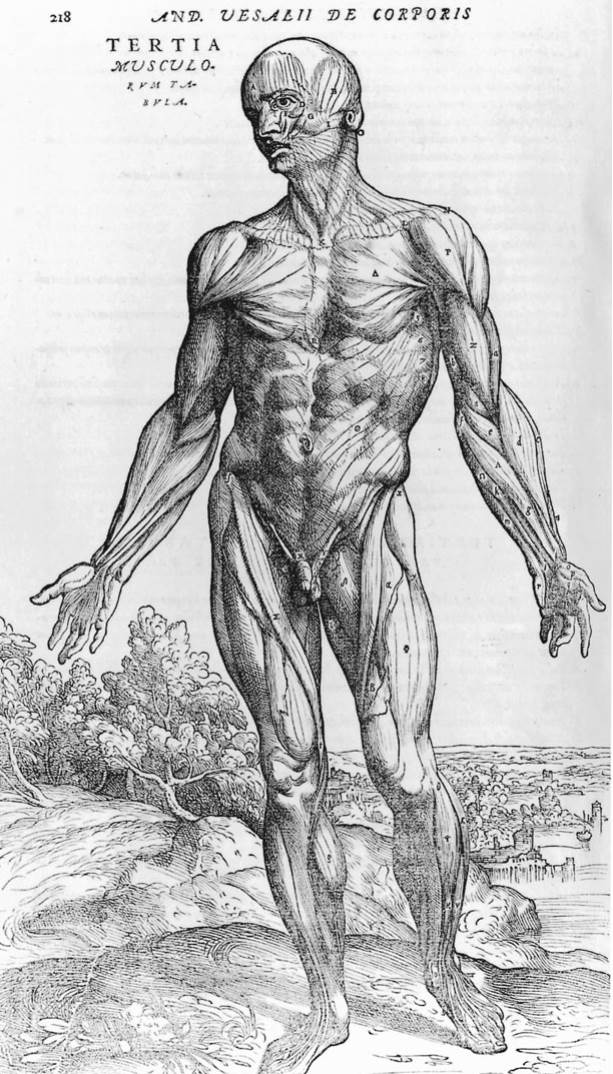

This interdisciplinary synergy is exemplified by the Renaissance anatomist Andreas Vesalius, who published his seminal work De humani corporis fabrica in 1543. His expertise was honed as a military surgeon, responding to new wounds from the Military Revolution, as much as by artistic needs. His work inspired contemporaries like Gabriel Fallopius and Bartolomeo Eustachi, who identified unknown anatomical structures. This tradition culminated in William Harvey's revolutionary discovery of the systemic circulation of the blood in 1628, a definitive break from the anatomical doctrines of Galen and Aristotle.

Fig. 11.1. The new anatomy. With the creation of gunpowder weapons, physicians and surgeons were confronted with treating more severe wounds and burns. A military surgeon, Andreas Vesalius, produced the first modern reference manual on human anatomy in 1543, the same year that Copernicus published his book on heliocentric astronomy.

Concurrently, magic and the occult sciences formed a defining element of Renaissance natural philosophy. This broad domain included astrology, alchemy, Neoplatonism, and the Cabala, ranging from "natural magic" involving technical marvels to spiritual intellectual enterprises. Central to its legitimacy was the recovery of the Hermetic corpus, a philosophy positing occult correspondences between the microcosm (human body) and the macrocosm (universe). Hermeticism affirmed that a learned magus could command nature's hidden forces—a concept that flowed into later scientific ideas like Newton's universal gravity. This anti-Aristotelian, extra-university tradition offered a framework for understanding and operating upon nature, aligning closely with the early forces of the Scientific Revolution.

The spiritual landscape was equally transformed by the Protestant Reformation, which shattered the unity of the Catholic Church and challenged religious authority, notably of the Vatican. Beginning with Martin Luther's Ninety-Five Theses in 1517, it sparked centuries of conflict, culminating in the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). This movement secularized authority and created a backdrop of theological ferment that deeply affected scientists like Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, and Isaac Newton, who grappled with the interplay between faith and reason.

A more pragmatic but persistent issue was calendar reform. The Julian calendar, instituted by Julius Caesar, had fallen out of sync with the solar year by roughly ten days by the sixteenth century, complicating the calculation of Easter. Popes Sextus IV and Leo X attempted reform, consulting figures like Nicholas Copernicus, who insisted that accurate astronomical theory must precede any practical adjustment. This problem underscored the growing need for precise observational science to inform civil society, further entwining scientific advancement with practical governance.

The convergence of these factors—global exploration, print technology, artistic inquiry, anatomical discovery, occult philosophy, religious upheaval, and practical needs like calendar reform—created a unique historical crucible. This environment encouraged empirical investigation, challenged ancient authorities, and fostered new institutions for knowledge production. The Scientific Revolution was not merely an intellectual shift but a complex societal transformation where changing worldviews, technological capabilities, and practical demands intersected to redefine humanity's understanding of the natural world and its place within it. The legacy of this period established the foundational methodologies and institutional frameworks for modern science.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;