Johannes Kepler: The Mystical Mathematician Who Revolutionized Astronomy

The intellectual journey of Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) challenges the simplistic view that scientific progress is driven solely by internal logic. His early and enduring obsession with astrology and number mysticism fundamentally shaped his scientific achievements and redirected the course of the Scientific Revolution. Emerging from an impoverished and troubled family—his father a mercenary and his mother later tried for witchcraft—Kepler attended Lutheran schools and the University of Tübingen as a gifted scholarship student. A chronically unwell and myopic individual who once compared himself to a "mangy dog," Kepler nonetheless saw astrology as an ancient, valid science, earning a steady income from casting horoscopes and writing prognosticatory almanacs. His conversion to the Copernican system was immediate, finding its mathematical harmony a pleasing revelation of the divine order in nature.

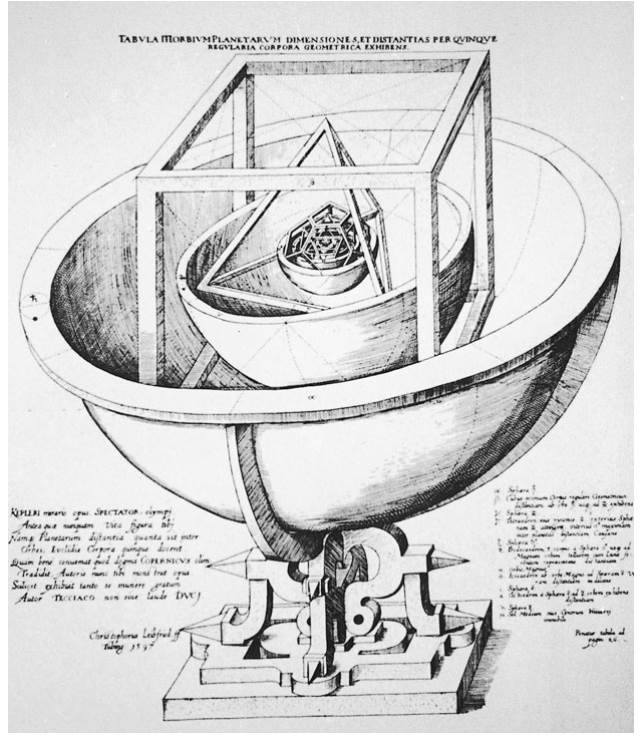

Kepler initially pursued theological studies, but before completing his degree, authorities at Tübingen nominated him for a post as a provincial calendar maker and mathematics teacher at the Protestant high school in Graz, Austria. He proved to be a poor instructor, with so few mathematics students that he was assigned to teach history and ethics instead. It was in this pedagogical setting, on July 19, 1595, that Kepler experienced a profound revelation while discussing the five Platonic solids—the cube, tetrahedron, octahedron, icosahedron, and dodecahedron. His mystical insight was that these perfect geometric forms might define the universe's structure by spacing the six known planetary orbits around the Sun. This inspiration led to his first major work, Mysterium Cosmographicum (The Mystery of the Universe), published in 1596, which was the first openly Copernican treatise in over half a century.

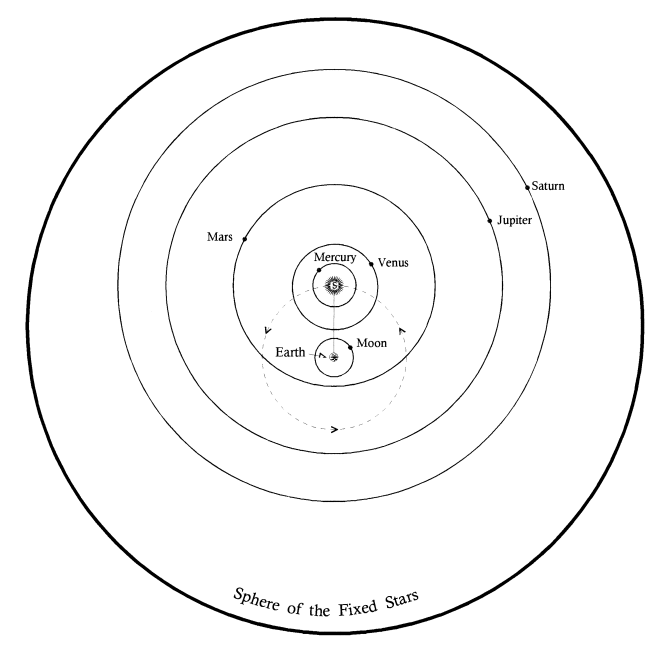

Fig. 11.5. The Tychonic system. In the cosmological model developed by Tycho Brahe, the Earth remains stationary at the center. The Sun orbits the Earth, while all other planets revolve around the Sun. Tycho’s system was scientifically robust for its time, solving several persistent astronomical problems, but it ultimately failed to gain wide acceptance.

Driven from Graz in 1600 by the Catholic Counter-Reformation and his refusal to convert, Kepler found refuge in Prague as an assistant to the renowned astronomer Tycho Brahe. Tycho tasked Kepler with analyzing the orbit of Mars, leveraging Tycho’s unprecedentedly accurate observational data. This assignment was fortuitous, as Mars has the most eccentric orbit (the most non-circular) of the visible planets. Kepler undertook this problem with intense dedication over six years, producing roughly 900 pages of manuscript calculations in a pre-calculator era. His commitment was to reconcile the data with Copernican theory and his own celestial harmonies, leading to an epic intellectual struggle. At one point, his circular model fit the data within eight minutes of arc, but knowing Tycho’s data was accurate to four minutes, he rejected this near-success, a decision underscoring his rigorous standards.

Fig. 11.6. The mystery of the cosmos. In his Mysterium Cosmographicum (1596), Johannes Kepler hypothesized that the spacing of the six known planetary orbits could be explained by nesting them within and around the five regular Platonic solids.

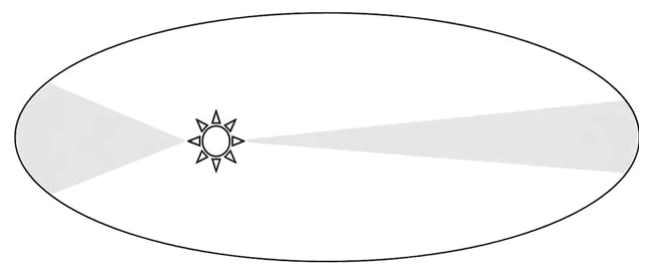

A second flash of insight, stemming from a mathematical connection involving the secant of an angle, finally led to a breakthrough. Kepler described it as awakening to a "new light." He conclusively demonstrated that planets orbit the Sun not in perfect circles but in ellipses, overthrowing a metaphysical cornerstone of astronomy that had stood since Plato. Published in his 1609 work, Astronomia Nova (A New Astronomy), this discovery formed the basis of his first two laws of planetary motion: 1) Planets move in elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus, and 2) A planet's radius vector sweeps out equal areas in equal times (the law of equal areas), meaning planetary speed is not uniform. This work truly constituted a "new astronomy," with the Sun now physically central to the system.

Fig. 11.7. Kepler’s elliptical motion of the planets. Based on Tycho Brahe’s data, Johannes Kepler broke with the ancient doctrine of uniform circular motion. He formulated three fundamental laws: 1) Elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus; 2) The law of equal areas; and 3) The harmonic law, where the square of a planet's orbital period is proportional to the cube of its semi-major axis (t² ∝ r³). Kepler derived these laws from observation and geometry, lacking a complete physical explanation for the motions he described.

After Tycho's death, Kepler remained in Prague as Imperial Mathematician to Emperor Rudolf II until 1612, later securing a position in Linz, Austria. During this tumultuous period of the Thirty Years' War, he produced seminal works: the Epitome of Copernican Astronomy (1618–21), which effectively presented his own elliptical system, and the Rudolphine Tables (1627), highly accurate astronomical tables based on Tycho's data and heliocentric theory. In 1619, he published Harmonices Mundi (The Harmony of the World), a culmination of his lifelong search for cosmic order, exploring astrological relations, planetary metals, and the music of the spheres. Buried within this mystical text was his empirical third law: the harmonic law (t² ∝ r³).

Having discarded uniform circular motion, Kepler faced the challenge of providing a new celestial dynamics. He initially proposed an anima motrix (moving soul) emanating from the Sun. Later, influenced by William Gilbert's work on magnetism (De Magnete, 1600), he posited a vis motrix (moving force), a magnetic power from the Sun that propelled and guided the planets. While this magnetic astronomy was a pioneering attempt at a physical cause, it was not mathematically rigorous and left unresolved questions, such as how the force acted tangentially to sweep planets along. Thus, after Kepler, the fundamental question of what force governed planetary motion remained open.

Kepler died of a fever in 1630 while traveling to collect debts owed to him. His work did not immediately culminate the Scientific Revolution; contemporaries like Galileo Galilei largely rejected his ideas, and he was often viewed as an eccentric mystic. However, his three laws of planetary motion provided the crucial descriptive foundation for Isaac Newton's later theory of universal gravitation. Kepler's legacy is a powerful testament to how personal belief, mystical intuition, and relentless empirical analysis can intertwine to produce transformative scientific change.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;