The Trial of Galileo and the Northward Shift of the Scientific Revolution in the 17th Century

The trial and punishment of Galileo Galilei by the Roman Inquisition in 1633 did not terminate scientific activity in Italy, but it profoundly suppressed its scope and ambition. The intellectual atmosphere remained repressive, with church authorities maintaining vigilant oversight. Copernicanism and expansive cosmological theorizing became prohibited domains, compelling Italian researchers to retreat into safer, strictly observational astronomy. A modest tolerance emerged only a century after Galileo’s death, marked by an Italian edition of his works sanctioned by the liberal Pope Benedict XIV. The Catholic Church did not authorize the teaching of Nicolaus Copernicus’s heliocentric model until 1822, removing his work from the Index of Prohibited Books in 1835. Galileo himself did not receive a full rehabilitation until the 1990s, underscoring the enduring impact of his condemnation.

The failure to establish a lasting Galilean school in Italy can be partly attributed to Galileo himself and the prevailing patronage system. During the early controversies of the 1610s, Galileo had followers and, acting as a minor patron, secured positions for some, like Benedetto Castelli at the University of Pisa. However, as a courtier, he did not formally train students in an academic setting. Only in his final years did Vincenzio Viviani and Evangelista Torricelli join him as assistants. While the mathematician Francesco Bonaventura Cavalieri was a genuine pupil and his son, Vincenzio Galilei, continued work on the pendulum clock, most direct descendants, except Viviani, were gone by 1650. Thus, the patronage model ultimately robbed Galileo of a sustained scientific legacy.

A defining characteristic of the Scientific Revolution following 1633 was the geographical migration of scientific leadership northward from Italy to Atlantic states like France, Holland, and England. In France, a vibrant community of independent scholars emerged, including Pierre Gassendi, Pierre Fermat, Blaise Pascal, and René Descartes. Despite their insulation from direct Roman authority, Galileo’s trial exerted a palpable chilling effect; Descartes, for instance, halted publication of his Copernican treatise, Le Monde, upon hearing the news in 1633. This self-censorship illustrates the transnational shadow cast by the Inquisition’s actions.

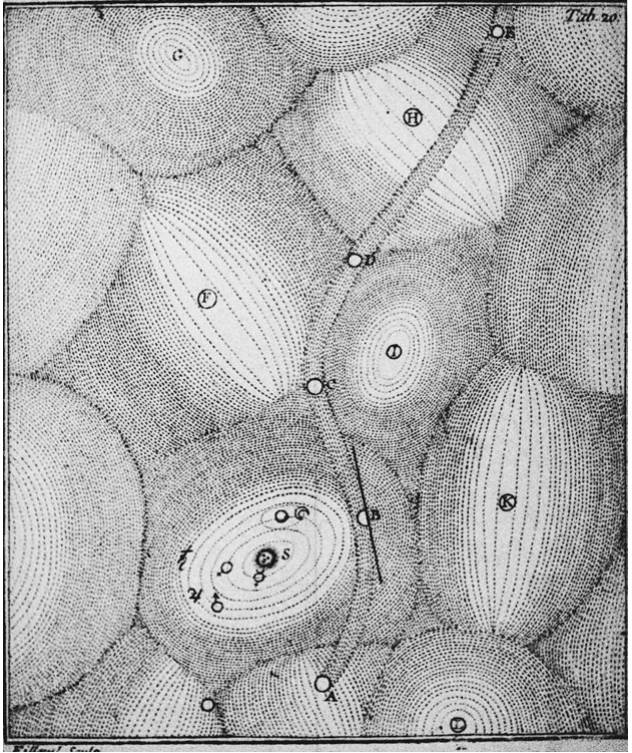

René Descartes ascended as the preeminent intellectual leader of the new science. A Jesuit-trained polymath, he retired from soldiering at age thirty-two to devote himself to philosophy and science. His fame rests on foundational contributions to algebra and analytical geometry, including Cartesian coordinates, as well as original work in optics and meteorology. His seminal Discourse on Method (1637) tackled the production of scientific knowledge, while his comprehensive Principles of Philosophy (1644) presented a full mechanical cosmology designed to supplant Aristotelian physics. Descartes’s heliocentric vortex theory, depicting planets swept around the sun in ethereal whirlpools, offered a systematic, if mathematically vague, alternative that aimed to cap the controversies ignited by Copernicus.

Descartes’s radical mechanization of the universe proposed that the world functioned entirely as a complex machine governed by laws of mechanics and impact. This extended to physiology, where he provided mechanical explanations to challenge Aristotelian-Galenic doctrines. While his system faced criticism, it synthesized the century’s discoveries into a coherent framework, making Cartesian natural philosophy the dominant post-1650 battleground. The central question in science became whether Descartes was correct, cementing his role as a pivotal figure who provided a comprehensive explanatory alternative to all preceding systems.

Descartes produced much of his work while residing in the tolerant Dutch Republic, which itself fostered significant scientific talent as part of the northward shift. Notable Dutch contributors included the engineer Simon Stevin, the atomist Isaac Beeckman, and the preeminent Christiaan Huygens, who became the leading advocate for mechanical philosophy in the latter half of the seventeenth century. The Low Countries also became a center for pioneering microscopic investigation, led by the draper-turned-scientist Anton van Leeuwenhoek. His lenses revealed a hidden “world of the very small,” including blood corpuscles, spermatozoa, and myriad animalcules.

Leeuwenhoek’s countryman, Jan Swammerdam, advanced microscopic technique through exquisite dissections of insects and plants. They were joined by the Italian Marcello Malpighi and the Englishman Robert Hooke, whose Micrographia (1665) showcased stunning engraved observations. These pioneers primarily used single-lens microscopes, where technical skill was paramount. However, unlike the telescope, which gained universal acceptance in astronomy, the microscope in the seventeenth century often raised more questions than it answered. Interpreting images of insect anatomy or capillary circulation lacked a shared intellectual framework, hindering consensus. This divergence highlights that instruments alone do not establish research traditions; consistent theoretical understanding is required. The compound microscope would not become standard laboratory equipment until the nineteenth century under new scientific conditions.

Fig. 12.5. Descartes’s system of the world. The constitution of the universe was an open question. The great French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes responded by envisioning a universe filled with an aetherial fluid sweeping the planets and other heavenly bodies around in vortices. The figure depicts a comet crossing the vortex of our solar system.

England, another Protestant maritime power, cultivated a formidable scientific community in Galileo’s wake. Early figures included the court physician William Gilbert, with his seminal work on magnetism, and William Harvey, who discovered the circulation of blood in 1618. The philosopher Francis Bacon championed empirical methodologies, while Robert Boyle pioneered experimental chemistry. The era culminated with the unparalleled achievements of Isaac Newton. Institutional support was crucial, provided by the Royal College of Physicians (1518), Gresham College (1598), and later the Royal Society of London (1662) and the Royal Observatory at Greenwich (1675). Crown-endowed professorships at Oxford and Cambridge further catalyzed this flourishing, ensuring England’s central role in the concluding act of the Scientific Revolution, a movement that had decisively shifted north following the silencing of Galileo in Italy.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;