Galileo Galilei’s Final Masterpiece: The Two New Sciences and Its Revolutionary Mechanics

In December 1633, the aging and humiliated Galileo Galilei, a prisoner of the Inquisition, was confined to his home outside Florence. Attended by his daughter, Virginia, and nearly blind, the seventy-year-old scholar nevertheless embarked on his culminating scientific work. This effort resulted in his 1638 publication, Discourses on Two New Sciences (often called the Discorsi), a treatise many consider his true masterpiece. Within it, Galileo detailed his groundbreaking mathematical analysis of the strength of materials and his revolutionary law of falling bodies, contributions central to the Scientific Revolution of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The Two New Sciences showcases Galileo's genius not as an astronomer, but as a pioneering mathematician and experimental physicist. To compose this work, he deliberately returned to research notes predating his astronomical fame and the subsequent controversies. He focused on theologically safe, yet profoundly innovative, investigations into how beams break and objects move. This strategic shift allowed him to contribute foundational knowledge to mechanics while avoiding further conflict with Church authorities.

Published covertly in Protestant Holland by the Elsevier press, the book is structured as a dialogue over four "days," featuring the same interlocutors—Salviati, Sagredo, and Simplicio—from his earlier Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems. In this later work, however, the characters represent the chronological evolution of Galileo's own thought: Simplicio embodies his early Aristotelian phase, Sagredo a middle Archimedean period, and Salviati his mature, revolutionary views. The treatise is markedly more mathematical than its predecessor, firmly establishing mechanics as a mathematical science.

The scene opens at the Arsenal of Venice, Europe's most advanced industrial enterprise, a setting Galileo used to rhetorically juxtapose science and technology. This location prompts a discussion on practical engineering problems, leading into the first two "days," which many historians have overlooked in favor of the more abstract later sections. Here, Galileo explores the cohesion of bodies and the breaking strength of materials, tackling diverse topics like scaling theory, fluid nature, and the isochronism of the pendulum.

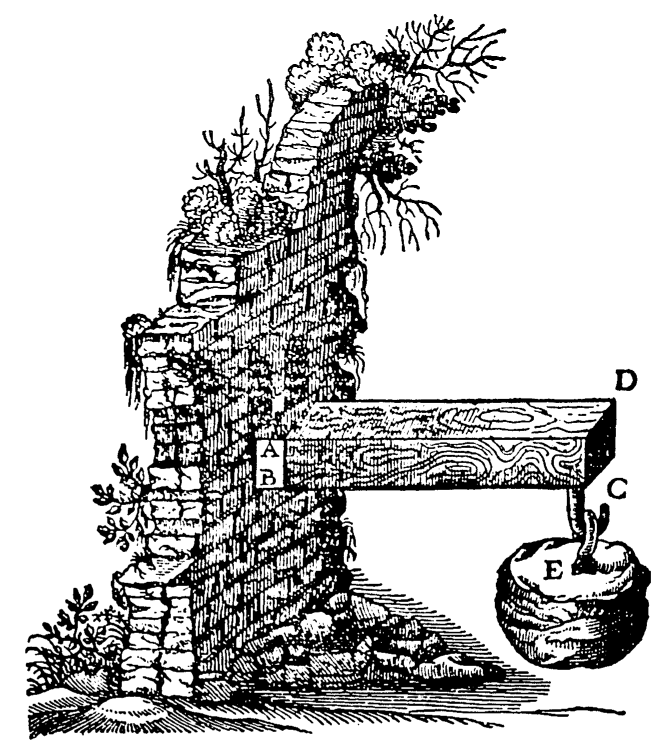

Figure 12.3. The strength of materials. While under house arrest in 1638, the 74-year-old Galileo published the Two New Sciences, formulating the law of falling bodies and deducing that a beam's strength is proportional to the square of its cross-sectional depth.

In the second day, Galileo extends ancient mechanics by mathematically analyzing a loaded beam or cantilever. He investigated the internal stresses caused by external loads and the beam's own weight, a problem of great interest to architects and engineers. Although his assumption about stress distribution was flawed, he correctly concluded that a beam's flexural strength is proportional to the square of its depth. Despite this theoretical advance, contemporary artisans met his findings with indifference, relying instead on proven empirical rules.

The more celebrated third and fourth days present Galileo's second new science: the study of local motion, or motion near the Earth. He systematically overthrew the Aristotelian dogma that fall speed is proportional to weight, reconceptualizing the medium of fall as a mere "impediment." This revolutionary shift struck at the core of Aristotelian physics and was central to dismantling the prevailing worldview. Galileo's intellectual journey to this law was complex, involving a decades-long "process of discovery" where he grappled with factors like weight, density, medium resistance, and time.

His law of falling bodies states that all objects, regardless of mass, fall with the same uniform acceleration in a vacuum, with the distance traveled proportional to the square of the elapsed time (s ∝ t²). It is crucial to note this is a kinematical law—it describes how bodies fall, not why. By focusing on mathematical description over causal explanation, Galileo demonstrated the power of kinematics alone. Historians also note that similar kinematical rules were discussed centuries earlier by the Mertonians or Calculators at Oxford, but Galileo insisted his findings described the real, physical world.

The role of experiment in Galileo's science is nuanced. While often called the "father of experimental science," he did not follow a simplistic Scientific Method of hypothesis-testing. Experiments for him served to demonstrate and confirm conclusions already reached through reasoning. The famous anecdote of dropping balls from the Leaning Tower of Pisa is likely apocryphal as a test of his law, though he may have performed demonstrations to challenge Aristotelian views. His documented inclined plane experiment, using a water clock for timing, was designed to illustrate his mathematically derived principles, not to test them in the modern sense.

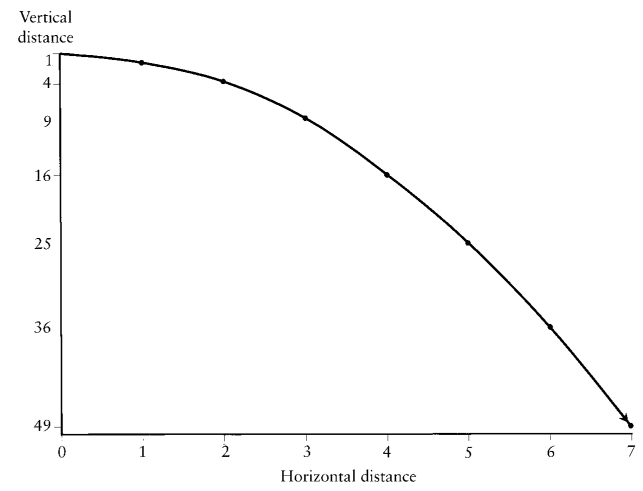

Figure 12.4. Parabolic motion of projectiles. Galileo decomposed projectile motion into two components: uniform acceleration downward and uniform horizontal motion. Their combination produces a parabolic path, recasting this ancient problem into its modern form.

In the fourth day, Galileo extended his analysis to projectile motion, combining his law of fall with a revolutionary concept of inertia. He proposed that a projectile's path is a compound of natural downward acceleration and innate, persistent horizontal motion. Crucially, Galileo's version was circular inertia, believing objects moved horizontally along the Earth's curvature. This concept, different from the later rectilinear inertia of Newton and Descartes, nonetheless removed a major objection to Copernicanism by explaining why objects are not left behind by a moving Earth.

From this analysis, Galileo derived the parabolic motion of projectiles, a theoretical breakthrough with clear applications in ballistics. He even published range tables for gunners, yet this practical application had negligible impact on contemporary artillery practice, which relied on centuries of empirical expertise. Galileo acknowledged unresolved problems, such as quantifying force and momentum, wistfully noting his desire to measure the "force of impact"—a challenge that would fall to Isaac Newton.

Galileo died under house arrest in 1642, the year of Newton's birth, having laid the essential groundwork for classical mechanics. His Two New Sciences stands as a testament to resilient scientific inquiry, transforming fundamental concepts of motion, matter, and strength that would fuel the ongoing revolution in natural philosophy.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;