Galileo Galilei: A Pivotal Figure in the Scientific Revolution and Renaissance Science

The life and influential career of Galileo Galilei progressed through distinct historical stages, deeply rooted in his Tuscan identity. Born in Pisa and raised in Florence, his father served the Medici court as a professional musician. Initially enrolling as a medical student at the University of Pisa, Galileo secretly studied mathematics, eventually securing paternal consent to pursue this less conventional path. Through established patronage networks, he obtained his first academic appointment at Pisa in 1589 at age twenty-five, marking his formal entry into the scholarly world.

Galileo initially adhered to the medieval model of a university-based career in mathematics and natural philosophy. He served as a professor for three years in Pisa before moving, again via patronage, to the University of Padua in the Venetian Republic in 1592. His status and salary there were modest, compelling him to supplement his income by tutoring students and selling an instrument he invented, the geometric and military compass. During this period, he began a long-term relationship with Marina Gamba, with whom he had three children, while his intellectual ambitions were stifled by a heavy teaching load that he felt hindered his research.

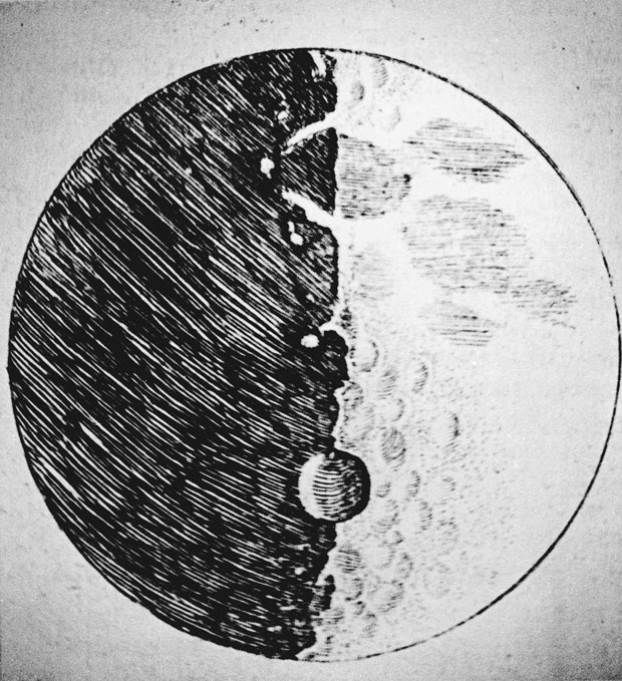

A pivotal transformation occurred in 1609 when Galileo learned of a Dutch invention, the telescope. He grasped its optical principles, crafted superior versions with up to 30x magnification, and boldly directed his instrument toward the heavens. His revolutionary observations, published in 1610 in the pamphlet Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger), revealed a cratered lunar landscape, myriad stars composing the Milky Way, and, most significantly, four moons orbiting Jupiter. He named these the Medicean Stars, dedicating his work to Cosimo II de' Medici, a calculated move to seek patronage.

These telescopic discoveries were not instantaneous but required meticulous interpretation of visual data over time. Galileo deduced lunar mountains by analyzing shifting shadows and confirmed the moons of Jupiter through protracted positional tracking. His empirical evidence soon became incontrovertible, forcefully reopening the debate concerning the true cosmological system of the world. These findings challenged the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic worldview and provided critical support for the Copernican heliocentric model.

Fig. 12.1. Galileo’s Starry Messenger. In his famous pamphlet published in 1610, Galileo depicted the results of the observations he made with the telescope. He showed, contrary to accepted dogma, that the moon was not perfectly smooth and had mountains.

Galileo astutely leveraged his newfound fame for a major career transition, moving from Padua to Florence as Chief Mathematician and Philosopher to the Medici court. This move, the culmination of long courtship, exchanged the security of a Venetian life-tenure for a prestigious, well-salaried court position offering freedom from teaching. The Medici, in turn, enhanced their reputation by associating with a celebrated intellectual. This role as a scientific courtier elevated Galileo’s social and intellectual status, placing his mathematical philosophy on par with traditional natural philosophers.

His career exemplifies a new, Renaissance model for organizing science, shifting from the medieval university to the princely court. While his Aristotelian opponents remained entrenched in academia, Galileo operated within a patronage system that provided crucial social and financial support for scientific work. Courts like the Medici’s employed various experts, seeking both practical utility and the reflected glory that learned clients bestowed. This system legitimated the emerging social role of the scientist and frequently involved its members in the intellectual controversies of the age.

The Scientific Revolution was not primarily driven within universities; Renaissance courts provided the essential new milieu. Patronage constituted a complex cultural exchange beyond simple service procurement, involving hierarchies of clients and patrons who gained prestige and engaged in learned disputes. This pattern of court-science, evident in Galileo’s career and that of contemporaries like Kepler in Prague, persisted into the 18th century, influencing even Isaac Newton.

Complementing courts, Renaissance academies emerged as vital extra-university institutions for science. These learned societies, often dependent on a patron, arose in opposition to academic Aristotelianism. An early example was the Academy of the Secrets of Nature (Academia Secretorum Naturae) in Naples, founded by the natural magician Giambattista Della Porta, author of the influential Magia naturalis.

The most significant for science was the Accademia dei Lincei (Academy of the Lynx-Eyed), founded in Rome in 1603 by Federico Cesi. Initially including Della Porta, the academy later embraced Galileo’s methodologies following his discoveries. Galileo became a member in 1611, proudly using the title Lincean academician, and the academy published key works like his Letters on Sunspots and The Assayer. The Accademia dei Lincei provided Galileo with critical institutional backing; its collapse after Cesi’s death in 1630 left him more vulnerable before his trial. Ultimately, the Renaissance court and academy model paved the way for the later rise of state-sponsored national scientific academies.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;