Nicolaus Copernicus and the Heliocentric Model: A Scientific Revolution Analyzed

Nicolaus Copernicus: The Conservative Revolutionary. Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), born in Poland, spent much of his life as a church administrator, or canon, in a role secured through familial connections. Despite his seemingly conventional and timid disposition, he embarked on a intellectual journey that would fundamentally alter astronomy. After matriculating at the University of Cracow in 1491, he spent a decade in Italy studying law and medicine while absorbing the Italian Renaissance culture, which nurtured his astronomical interests. His early humanist endeavors included translating the works of the Greek poet Theophylactus, reflecting the scholarly milieu that shaped him. Crucially, Copernicus is best understood not as the first modern astronomer, but as the last great practitioner of the ancient tradition, seeking to restore Greek astronomy to its perceived original purity rather than to instigate a overt rebellion.

The Critique of Ptolemaic Astronomy and the Equant. Copernicus operated as a direct successor to Claudius Ptolemy, aiming to rectify what he saw as flaws in the prevailing geocentric model. His primary objection centered on the Ptolemaic system's failure to adhere strictly to the ancient mandate of uniform circular motion, particularly through its use of the equant point. This mathematical device allowed for the calculation of uniform angular motion from a point offset from the center of a planet's orbit, which Copernicus deemed a fictitious violation of true uniform motion. He repudiated this construct, describing the resulting geocentric model as an astronomical "monster" that could not adequately or elegantly explain planetary stations and retrogradations. His quest was for a more harmonious and consistent system, firmly rooted in classical principles.

The Heliocentric Hypothesis and Its Delayed Publication. For Copernicus, the solution was heliocentrism, the hypothesis placing the Sun at or near the center of the solar system and recasting Earth as a orbiting planet. He first outlined this concept in a brief anonymous manuscript, the "Commentariolus," circulated among astronomers after 1514. However, he delayed publishing his comprehensive work, "De revolutionibus orbium coelestium," due to both a fear of ridicule for its apparent absurdity and a possible belief that such profound ideas were not for the masses. The intervention of his protege, Georg Joachim Rheticus, who published an introductory notice ("Narratio Prima") in 1540, finally prompted Copernicus to consent. "De revolutionibus" was published in 1543, coinciding with the astronomer's death.

Methodology: Axioms and Aesthetic Motivation. Copernicus did not base his heliocentric model on new observations nor did he claim to definitively prove it. Instead, he treated heliocentrism as a postulate, much like the axioms in Euclidean geometry, and deduced its consequences through geometrical propositions. This approach was driven by aesthetic and ideological convictions; he found the Sun-centered system to possess superior simplicity and harmony, being more "pleasing to the mind" than the complex apparatus of Ptolemaic astronomy. Its revolutionary character lay in its capacity to resolve long-standing astronomical problems through a more coherent conceptual framework, appealing to a sense of celestial order and intellectual economy.

Explaining Planetary Retrograde Motion. The greatest explanatory simplicity of the Copernican system lay in its elegant account of planetary retrograde motion. In the geocentric model, this apparent backward loop in a planet's path required elaborate geometrical constructions. For Copernicus, it was a straightforward illusion of perspective caused by the relative motions of Earth and the other planets as they orbit the Sun at different speeds. As observed from a moving Earth, a superior planet like Mars will periodically appear to halt and reverse direction against the backdrop of the fixed stars, even though both planets are moving continuously forward. This natural explanation made the problematic "retrogradation" a direct and inevitable consequence of the heliocentric postulate itself.

Additional Explanatory Advantages of the Model. The heliocentric hypothesis offered further coherent explanations for observed phenomena. It naturally accounted for the fact that the inferior planets, Mercury and Venus, never appear far from the Sun in the sky—a fact Ptolemaic astronomy addressed with ad-hoc measures. In the Copernican system, their orbits lie inside Earth's, forcing their apparent proximity. Furthermore, it established a definite and logical planetary order (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn) based on orbital periods, whereas the Ptolemaic ordering was ambiguous. This arrangement also allowed for the first reliable calculations of the relative distances of planets from the Sun, providing a sense of the solar system's scale.

The Sun's Central Role and Neoplatonic Influence. Copernicus assigned the Sun a position of paramount physical and almost metaphysical importance. In a passage from "De revolutionibus" resonant with Neoplatonic thought, he described the Sun enthroned at the center, illuminating all, calling it the "Lamp," "Mind," and "Ruler of the Universe." This philosophical alignment with sun-centric symbolism reinforced his architectural choice for the cosmos. He attributed two primary motions to Earth: a diurnal rotation on its axis explaining daily celestial motion, and an annual revolution around the Sun accounting for the Sun's yearly path. However, Copernicus also postulated a critical third motion of the Earth, essential to his fusion of new ideas with ancient cosmology.

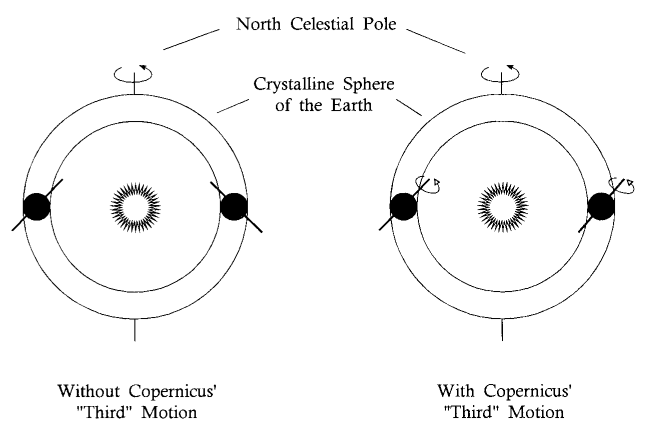

The Third Motion and Crystalline Spheres. Copernicus's third motion reveals his deep connection to traditional astronomy, as he retained the concept of planetary bodies embedded in solid, transparent crystalline spheres. He believed these spheres physically carried the planets, meaning Earth was transported within its own sphere. To maintain Earth's axial tilt constant at approximately 23.5 degrees—essential for seasons—as its sphere revolved, he introduced an additional conical wobble of the axis. This complex motion ensured the north celestial pole pointed steadily toward Polaris throughout the year. By slightly adjusting this motion's period, he also accounted for the slow precession of the equinoxes.

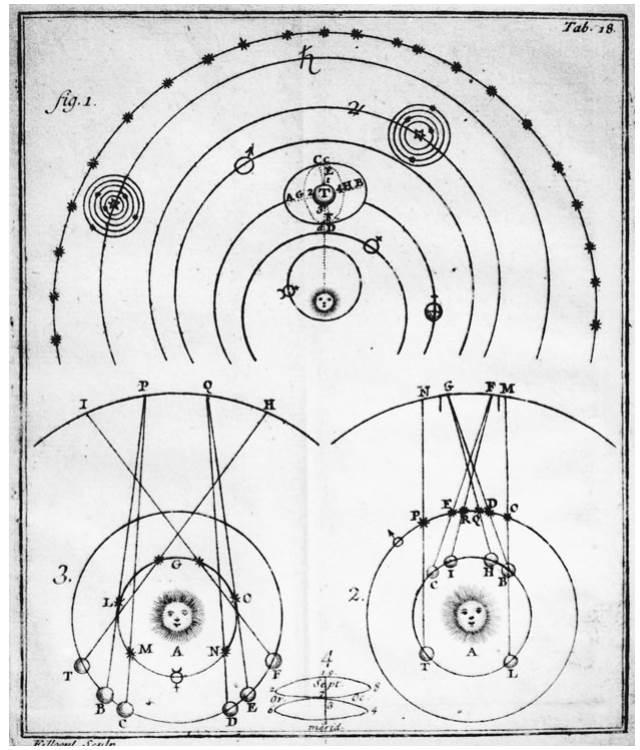

Fig. 11.2. Retrogradation of the planets in the heliocentric system. Copernicus provided a simple explanation for the age-old problem of stations and retrogradations of the planets. In the heliocentric system a planet’s looping motion as seen against the background of the fixed stars is only apparent, the result of the relative motion of the earth and the planet in question. In this eighteenth-century engraving, 2 depicts how the superior planets (Mars in this case) seem to retrograde; 3 depicts the inferior planet (Venus in this case).

Addressing Physical Objections with Modified Aristotelian Physics. Copernicus faced traditional Aristotelian objections to a moving Earth, such as why objects are not left behind or flung into space. His defense involved a modified Aristotelian physics. He argued that circular motion was natural for spherical bodies, so Earth's rotation and orbital transport were innate. Objects fell toward the center of the Earth, not the universe's center, because their "mother" Earth attracted them. He maintained that all earthly objects shared in Earth's natural motions, thus explaining why they co-move seamlessly. Qualitatively, this framework allowed his system to function, and its aesthetic appeal is most evident in the first book of "De revolutionibus," which presents the general theory.

Fig. 11.3. Copernicus’s third (“conical”) motion of the earth. To account for the fact that the earth’s axis always points in the same direction, Copernicus added a third motion for the earth in addition to its daily and annual movements.

Technical Complexity and Retention of Epicycles. Beyond its elegant foundation, "De revolutionibus" contained five additional books of dense, technical mathematical astronomy rivaling the complexity of Ptolemy's "Almagest." Committed to uniform circular motion but having rejected the equant, Copernicus was forced to retain an elaborate system of epicycles and eccentrics to model remaining irregularities in planetary speeds. Consequently, his final model was neither significantly more accurate nor simpler than refined Ptolemaic versions of his time; by some counts, he employed even more circles. This technical complexity meant his work remained accessible only to fellow mathematicians, as emphasized by the Platonic motto he included: "Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here."

The Problem of Stellar Parallax and Universe Scale. A major technical hurdle for Copernican astronomy was the absence of observable stellar parallax—the apparent shift in star positions due to Earth's orbital motion. Following Aristarchus, Copernicus argued the stars were immensely distant, making parallax undetectable. This defense, however, dramatically expanded the accepted size of the universe. While Ptolemaic cosmology placed the sphere of fixed stars at about 20,000 Earth radii, Copernicus required a distance of at least 400,000 Earth radii, implying staggeringly large star sizes. This colossal scale seemed implausible to many 16th-century contemporaries and remained a potent scientific counter-argument until parallax was finally measured in 1838.

Gradual Acceptance and the Role of Osiander's Preface. Acceptance of the Copernican model was slow and contested, hindered by technical issues like stellar parallax and the behavior of falling bodies. Theological objections also arose, though Copernicus had dedicated his work to Pope Paul III to preempt them. A significant factor in its initial toleration was an unauthorized preface added by the Lutheran theologian Andreas Osiander. This preface presented heliocentrism merely as a useful mathematical hypothesis for calculating planetary positions, not as physical truth. While Copernicus himself believed in the model's reality, Osiander's instrumentalist interpretation made the theory superficially palatable to both astronomers and religious authorities, inadvertently aiding its early diffusion.

Legacy and the "Revolution by Degrees". The influence of Copernican heliocentrism permeated astronomy gradually. Practical tools like the Prutenic Tables (1551), calculated by Erasmus Reinhold using Copernican parameters, improved predictive accuracy and even aided the Gregorian calendar reform of 1582. Yet, few astronomers fully embraced the physical reality of the moving Earth in the 16th century. Definitive proofs, like James Bradley's discovery of stellar aberration (1729) and Léon Foucault's pendulum demonstration of Earth's rotation (1851), came centuries later. Thus, the Copernican Revolution was not an immediate upheaval but a protracted transformation—a revolution by degrees that ultimately redefined humanity's place in the cosmos.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;