The Military Revolution in Early Modern Europe: Gunpowder, State Centralization, and the Path to Global Dominance

By the fourteenth century, Europe had developed several hallmarks of civilization, including intensified agriculture, population growth, urbanization, monumental architecture like Gothic cathedrals, and institutionalized higher learning. However, in its rain-watered environment that negated the need for large-scale hydraulic agriculture, Europe lacked the centralized authority and universal corvée (compulsory labor) typical of earlier Eastern empires. These components only emerged later, beginning decisively in the sixteenth century, driven by a unique Military Revolution. This historical dynamic, centered on gunpowder technology, fundamentally reshaped European politics, society, and its eventual global role.

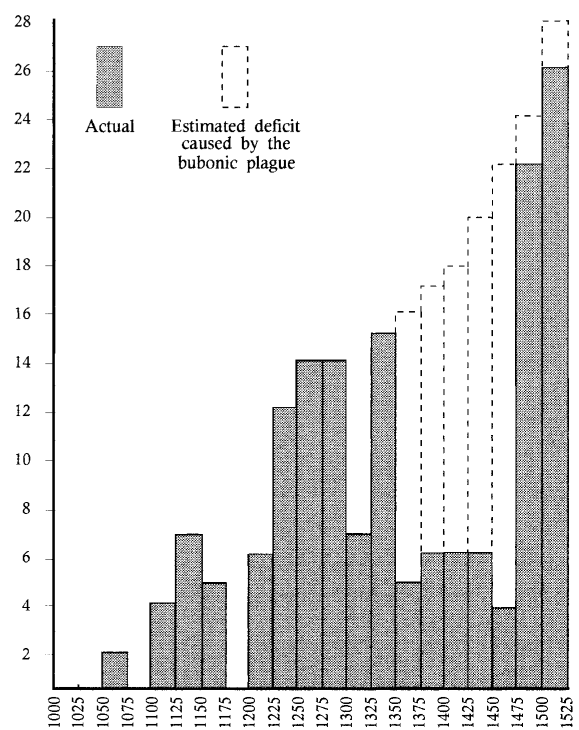

Fig. 10.4. The Plague. Also known as the Black Death, the plague struck Europe in 1347, depressing the amount of scientific activity. After more than 100 years Europe and European science began to recover.

The foundational technology of this revolution, gunpowder, originated in Asia. The Chinese invented gunpowder in the ninth century CE, developing fireworks, rockets, and by the mid-1200s, explosive bombs and early fire lances. Through technology transfer, likely via the Mongol Empire and Silk Road contacts, knowledge of gunpowder reached the Islamic world and Europe by the thirteenth century. While this early firearms technology was Chinese, the development of large cannon is first documented in Europe between 1310 and 1320. This technology then diffused rapidly back across Eurasia, becoming a universal Old World technology by 1500, with major centers in China, the Mughal Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and Europe.

Early artillery, like the immense Turkish bombards used at the Siege of Constantinople (1453) or "Mons Meg," were enormous, immobile siege weapons. European founders, engaged in intense interstate competition, actively refined casting techniques. A key innovation came in 1541 when England mastered casting iron cannon, which were far cheaper than bronze. This led to smaller, more mobile and numerous guns. The shift from massive siege guns to standardized, mobile field artillery and ship-mounted cannon proved militarily decisive, altering the dynamics of both land and naval warfare.

The "gunpowder revolution" transformed the European sociopolitical landscape by the late fifteenth century. It rendered the feudal knight and the military power of individual lords obsolete, as the new artillery and armies were prohibitively expensive. Only centralized governments with royal treasuries could finance the new warfare. This shift is evident in the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453), which began with knights and longbows and concluded with victory determined by gunpowder artillery. The new technology democratized military prowess momentarily, as seen with Joan of Arc, whose intuitive grasp of artillery placement brought success despite her lack of traditional military experience.

The fiscal demands of the new warfare were unprecedented. To fund standing gunpowder armies and navies, European states dramatically increased taxation. For example, French artillery's annual gunpowder consumption rose from 20,000 to 500,000 pounds between the 1440s and 1550s. Spanish military expenses ballooned from under 2 million to 13 million ducats in the late sixteenth century, leading to debt repudiation and crushing tax burdens. This fiscal-military need was a primary driver of political centralization, transferring power from local nobles to the centralized nation-state.

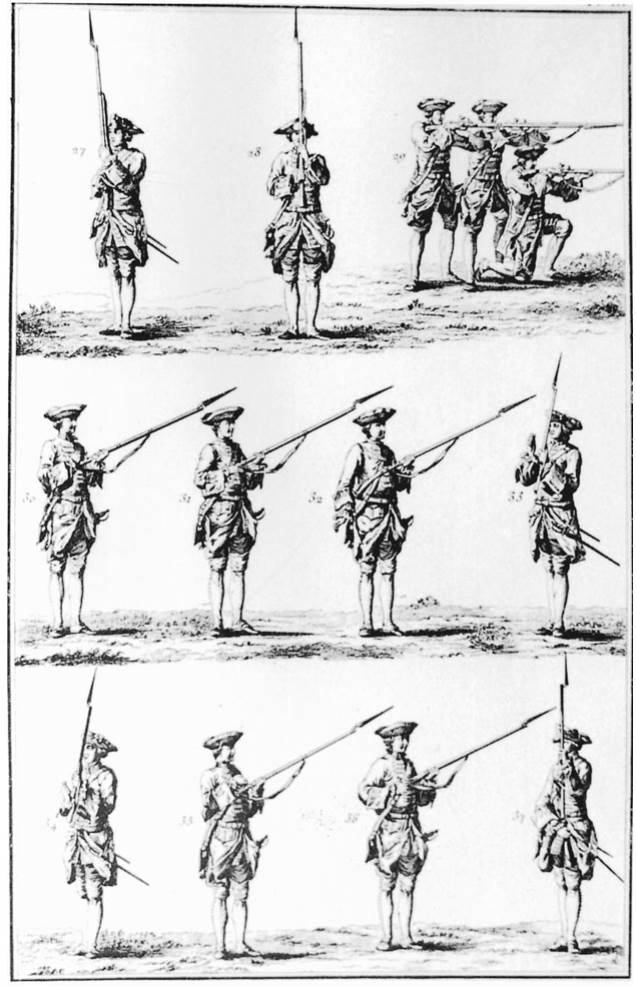

Fig. 10.5. Military drill. Although the musket had a much lower rate of fire than the bow and arrow, it struck with much greater force. The complex firing procedure led to the development of the military drill. Organizing, supplying, and training large numbers of soldiers armed with guns reinforced political trends toward centralization.

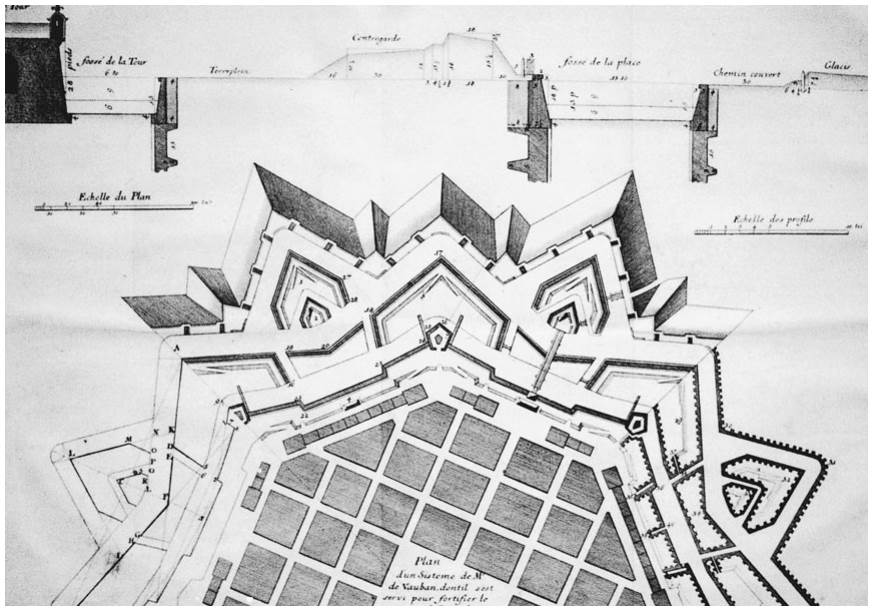

Further military reforms amplified this centralizing trend. The introduction of the musket and the military drill perfected by Maurice of Nassau created disciplined, volley-firing infantry. These new armies, alongside standardized artillery, rendered traditional forces like pikemen and cavalry obsolete. Consequently, army sizes exploded; the French army, for instance, grew from 150,000 to 400,000 under Louis XIV. The new warfare also mandated a defensive revolution: the trace italienne, or star-shaped bastion fort. These expensive, artillery-resistant fortifications further strained state resources, locking offense and defense in a costly spiral that only centralized states could sustain.

Thus, the Military Revolution produced effects analogous to hydraulic agriculture in ancient empires, forging centralized authority through the logistical and financial demands of military technology. Europe finally acquired the full suite of civilized institutions, with state-controlled arsenals, shipyards, and fortresses acting as modern public works, akin to ancient canals. Universal military conscription, later formalized, became the modern equivalent of the ancient corvée.

Fig. 10.6. Fortification. As the castle fell to the cannon it was replaced by a complex system of fortification with projections known as the trace italienne. While effective as a defensive system it proved to be extraordinarily expensive.

However, Europe's ecology prevented the rise of a unified empire. Unlike the vast, irrigated floodplains that sustained monolithic empires in the East, Europe's rain-fed agriculture and geographic diversity fostered multiple competing nation-states. The primary outcome was a system of competitive, centralized states like Spain, France, and England, locked in perpetual rivalry. This competitive fragmentation, rather than imperial unity, proved historically decisive. States that failed to adapt, like Poland, were absorbed. Pan-European institutions like the papacy or the Holy Roman Empire remained too weak to impose unity, ensuring a dynamic, multipolar continent.

A second major outcome was European colonialism and global expansion, enabled by a parallel revolution in naval warfare. The oared galley was replaced by the ocean-going, wind-powered galleon, armed with broadside cannon. New navigation techniques, like using the compass (a Chinese invention) and mastering oceanic wind patterns (the volta), were crucial. This gunned ship was a complex sociotechnical system, emerging from iterative improvements in rigging, gun ports, and sailing knowledge, not a predetermined design. It gave Europe unmatched naval power projection.

The global impact was immediate and profound. Vasco da Gama reached India (1498), Christopher Columbus the Americas (1492), and Hernán Cortés conquered the Aztec Empire with tiny, heavily armed forces. European naval technology enabled the extraction of resources and the establishment of colonial rivalries and mercantilist empires for centuries. By 1800, European powers dominated approximately 35% of the world's land and resources.

Contrary to later patterns, scientific thought played a minimal role in these early technological developments. Key inventions like gunpowder and the compass came from China without theoretical underpinnings. In Europe, practical artisans—gunners, foundrymen, shipbuilders—advanced technology through experience, skill, and rules of thumb, not applied science. Ballistics, metallurgical chemistry, and hydrodynamics remained underdeveloped. The causal arrow pointed from technology to science: states began patronizing science hoping for technical benefits.

This government support for science emerged first in the pioneering colonial powers. Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal promoted navigation and cartography. Portugal and Spain established state institutions like the Casa de la Contratación and royal chairs in navigation and cosmography to support their empires. They conducted systematic geographical and botanical surveys, like the Hernández expedition to the Americas. This model of state-sponsored science for colonial and military advantage was later adopted by all major European powers, institutionalizing science in a pattern reminiscent of other great civilizations, but within a competitive, state-driven framework.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;