The Foundations of Modern Science: Medieval European Universities and the Recovery of Knowledge

Prior to the twelfth century, higher learning in Europe north of the Alps was sparse, making the concept of a widespread “Dark Age” misleading. Following the Roman era, a thin veneer of literate culture persisted in monastery schools and through occasional scholars, overlaying a predominantly Neolithic village life. These monastic communities, with their scriptoria and libraries, served as minor centers of preservation. To ensure a supply of literate clergy for an illiterate society, Charlemagne decreed the establishment of cathedral schools in 789. Instruction within these early medieval centers remained elementary, focused on the trivium and quadrivium—the Seven Liberal Arts inherited from antiquity—with scientific inquiry largely subordinated to theology and religious needs.

Paradoxically, Irish monasteries at Europe's periphery cultivated sophisticated learning, including knowledge of Greek. Isolated scholars like Gerbert of Aurillac, later Pope Sylvester II, exemplified rare intellectual pursuits. After studying in Spain, Gerbert introduced instruments like the abacus and astrolabe to France, tapping into filtered Islamic learning. Despite such individual achievements, the overall intellectual landscape before the twelfth century remained elementary and socially marginal. The core of European life was still far removed from systematic scholarly investigation.

The emergence of the European university in the twelfth century marked a definitive institutional watershed. While Salerno was known for medicine earlier, the University of Bologna, organized as a guild of students, is typically recognized as the first. The University of Paris and the University of Oxford followed swiftly. This rise coincided with urbanization and wealth from agricultural improvements, as universities were inherently urban institutions requiring a student body with means and career prospects. Nearly eighty universities were established by 1500, creating a new, durable framework for learning.

The European university was a unique creation, modeled on medieval craft guilds. They existed as either student guilds (Bologna) or masters' guilds (Paris), operating as independent, chartered corporations with legal privileges. Unlike ancient scribal schools or Islamic madrasas, they did not rely on state patronage but enjoyed autonomy under loose church and state authority. This structure, granting rights to confer degrees and freedom from town control, placed universities in a middle ground between state-controlled bureaucracies and the individualistic tradition of Hellenic science.

These vibrant institutions trained the clergy, doctors, lawyers, and administrators needed by a flourishing medieval society. The graduate faculties of theology, law, and medicine provided advanced instruction, while the undergraduate arts faculty taught all students the liberal arts. Within this arts curriculum, the natural sciences found a home, particularly in the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music). Students pursuing higher degrees often earned a Master of Arts, where natural philosophy was core. Thus, science became a subject for intense study as a preliminary to professional training, though the medieval university was not primarily a research institution.

Before this curriculum could exist, the corpus of Greek and Islamic science needed translation into Latin. Following the Christian reconquest of Toledo in 1085, it became a central hub for translation teams. Jewish scholars played a crucial role, translating Arabic works into Hebrew or Spanish for Christian collaborators. Similar efforts occurred in Sicily and southern Italy. The motivation was often practical, focusing on medicine, astronomy, astrology, and alchemy. Through this monumental effort, works by Aristotle, Ptolemy, Euclid, and Galen, along with Islamic commentaries, became available to Europeans by 1200.

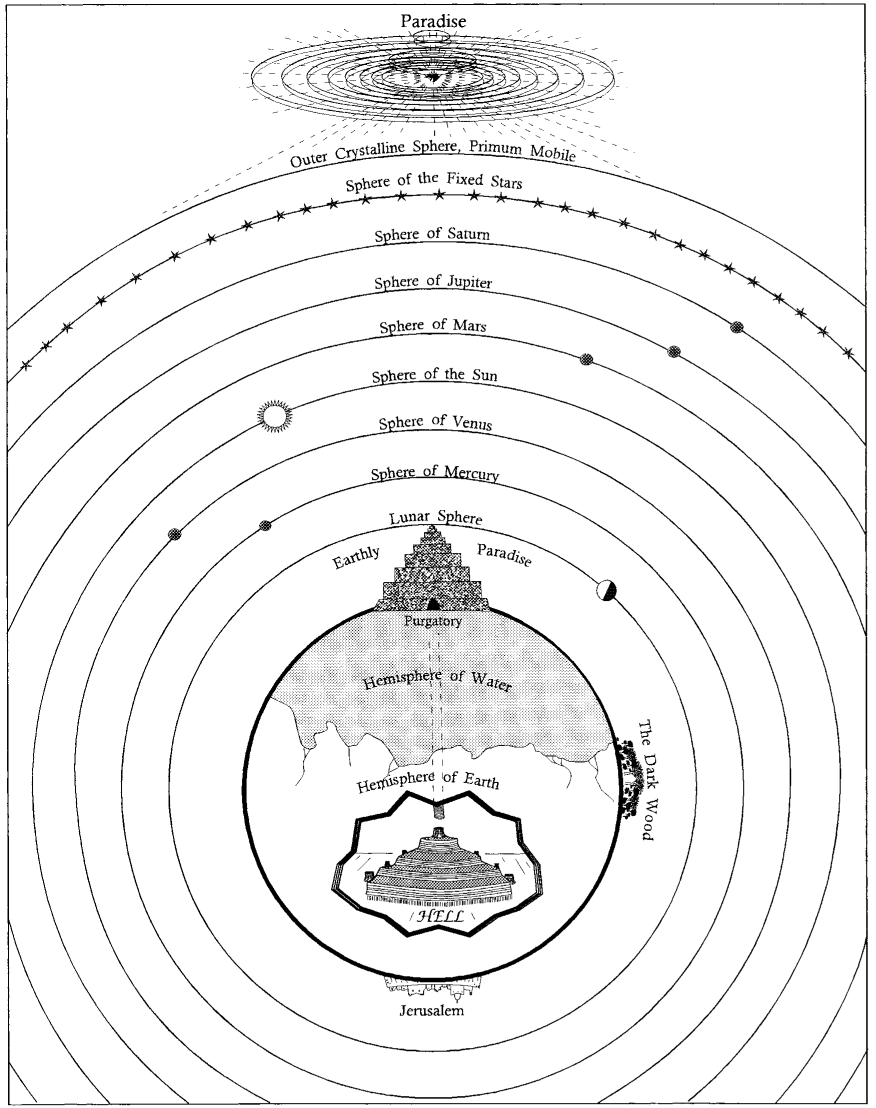

The thirteenth century became a period of assimilation and synthesis. Scholars, most notably Thomas Aquinas, worked to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy with Christian doctrine. This scholastic synthesis made Aristotle "the Philosopher," providing a comprehensive rational framework for understanding God, man, and nature. His logic and categories became the primary tools for intellectual inquiry. The universities' mission became the elaboration and defense of this integrated worldview, creating a coherent, geocentric vision of a hierarchically ordered cosmos, as later reflected in Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy.

Fig. 10.2. Dante’s scheme of the universe. In The Divine Comedy the early Italian poet Dante Alighieri developed the medieval portrait of the cosmos as a Christianized version of Aristotle’s worldview.

This unified worldview held that reason could complement revelation in understanding God's creation. However, when Aristotelian natural philosophy clashed with Church teaching, theology took precedence. Points of conflict included Aristotle's assertions on the eternity of the world and the mortality of the soul. The institutional tension was exacerbated as arts faculty masters promoted philosophy as an independent path to truth, challenging the theology faculty's domain.

These conflicts culminated in the Condemnation of 1277, issued by the Bishop of Paris, which prohibited 219 Aristotelian propositions. While seemingly a victory for conservative theology, its effects were complex. By emphasizing God's absolute power (potentia Dei absoluta) to create any kind of world, it inadvertently encouraged scholars to explore hypothetical alternatives to Aristotelian physics. This stimulated a flourish of "hothouse" scientific speculation, where natural philosophers like Jean Buridan and Nicole Oresme entertained novel ideas—such as a rotating Earth—as thought experiments, without claiming physical truth.

Medieval science was diverse and not slavishly Aristotelian. At Oxford, a more Platonic and mathematical tradition emerged, championed by Robert Grosseteste and Roger Bacon, who advocated for experimental methods. Significant progress occurred in optics, astronomy (e.g., the Alfonsine Tables), and mathematics, where Fibonacci introduced Hindu-Arabic numerals. Medical faculties advanced Galenic theory, and scholars like Albertus Magnus contributed to biology. This period also saw serious work in alchemy and natural magic.

A key scientific accomplishment was Jean Buridan's theory of impetus to explain projectile motion, modifying Aristotle's physics by proposing an internal motive force. While sometimes superficially compared to inertia, it remained firmly within the Aristotelian search for efficient causes. Similarly, Nicole Oresme made profound mathematical advances, using graphical methods to represent qualities and motion.

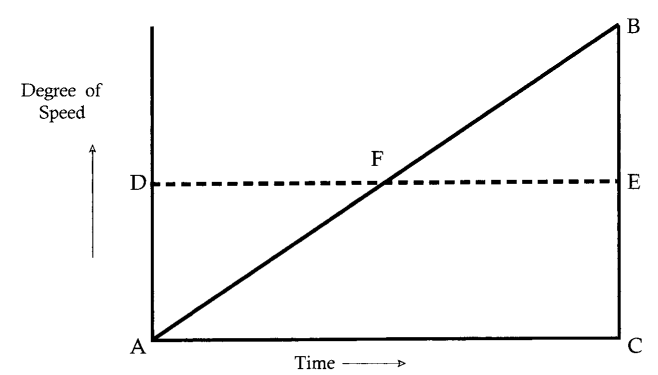

Fig. 10.3. Uniformly difform motion. In classifying different types of motion, the medieval scholastic Nicole Oresme (1320-82) depicted a motion that increases uniformly over time. He called it uniformly difform motion; we call it constant acceleration. Implicit in the diagram is the notion that the distance an accelerated body travels is proportional to the square of the time elapsed. Galileo later transformed Oresme’s abstract rules into the laws of motion that apply to falling bodies.

Oresme’s analysis contained the mathematical relationship (s ∝ t²) later known as Galileo’s law of falling bodies. However, Oresme did not apply his abstract analysis to real-world motion, highlighting a key characteristic of much medieval science: it was often a theoretical exercise within a theological framework.

The fourteenth century brought severe disruptions: the Little Ice Age, the Great Famine (1315-17), the Black Death, and the Hundred Years' War. These catastrophes decimated populations and disrupted institutions. However, the essential structures of learning survived. Universities recovered and expanded, and scientific scholarship rebounded, as indicated in demographic data on scholars (see figure 10.4).

In conclusion, medieval Europe constructed a durable institutional foundation with the university and a robust intellectual foundation through the recovery and critique of ancient science. Its historical significance lies not only in its own scholarly achievements but in laying the essential groundwork for the Scientific Revolution. The period demonstrates remarkable continuity, with the disruptions of the late Middle Ages causing a temporal dip but not a permanent break in the trajectory of European scientific thought.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;