The Genesis and Structure of Newton's Principia: A Foundation for Celestial Mechanics

In August 1684, Edmond Halley visited Isaac Newton at Cambridge to discuss a pressing scientific question. Earlier that year, Halley, Robert Hooke, and Christopher Wren had debated at the Royal Society the connection between Kepler’s laws of planetary motion and a hypothetical attractive force from the sun. Newton, recalling work from 1666, immediately stated that an inverse-square force law would produce an elliptical orbit. He later sent Halley a nine-page manuscript, "On the Motion of Orbiting Bodies," which outlined the core principles of celestial mechanics and was instantly recognized as revolutionary. This tract became the seed for Newton's monumental work, the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), published in 1687 under the Royal Society's aegis with Halley's crucial editorial support.

The Principia is a rigorously geometric treatise that begins with fundamental definitions of mass, force, and motion. Newton establishes his three laws of motion: the law of inertia; the proportionality of force to change in motion; and the principle of equal and opposite reaction. In preliminary sections, he discusses absolute space and time and demonstrates that Galileo’s law of falling bodies is a logical consequence of his own dynamics. This foundational framework subsumes earlier kinematic descriptions of motion within a new, causal physics of forces, establishing Newtonian dynamics as a comprehensive system.

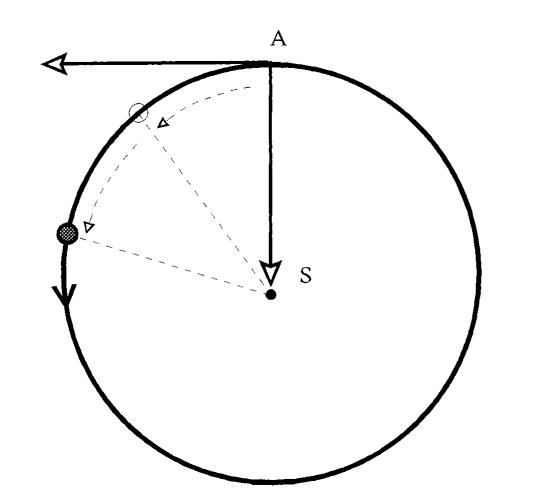

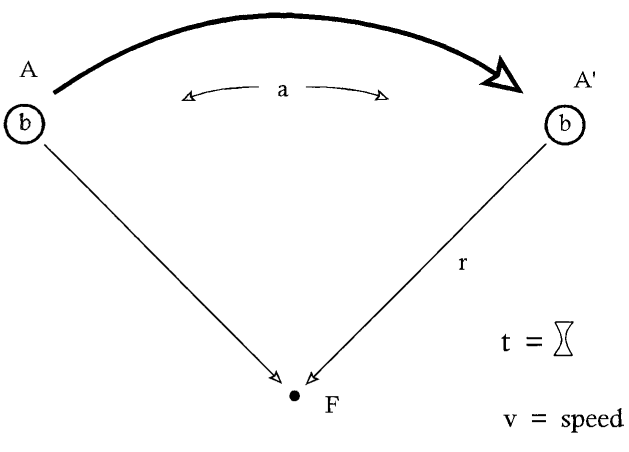

The work's core is divided into three books. Book I presents an abstract treatment of motion in free space, beginning with the geometric techniques of calculus (differentiation and integration). In its second section, "The Determination of Centripetal Forces," Newton proves that a body under a central force obeys Kepler’s second law (equal areas in equal times) and, crucially, the converse. Proposition IV and its corollaries contain a profound insight: if Kepler’s third law (the square of the orbital period is proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis) holds, then the centripetal force must vary inversely with the square of the distance. This is the first mathematical derivation of Newton’s law of universal gravitation.

Figure 13.2: Newton’s Principia. In Book I of his Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1687), Isaac Newton linked gravity to Kepler’s laws. The proposition shown demonstrates that a body moving inertially under a gravitational influence obeys Kepler’s Second Law, sweeping out equal areas in equal times.

The remainder of Book I expands this analysis to all conic sections, proves the gravitational effect of a sphere is equivalent to a point mass at its center, and develops the mathematical tools for orbital determination. Book II shifts to examine motion in resisting media, serving as a treatise on hydrostatics and hydrodynamics. This diversion was strategically aimed at dismantling the rival Cartesian system of cosmic vortices, concluding with Newton's devastating critique that planetary motion cannot be explained by such fluid vortices and must instead be governed by the mathematical laws already established.

Book III, titled "The System of the World," applies the abstract principles to the solar system. Newton presents the phenomena of a heliocentric system obeying Kepler's laws. Using data from the moon's orbit and the comet of 1680, he demonstrates that the same inverse-square law of gravity explains both celestial orbits and terrestrial falling bodies, famously proving "that the Moon gravitates towards the Earth." This elegant calculation unified celestial and terrestrial physics, resolving centuries of cosmological debate. The book concludes by outlining future research, including lunar theory, tides, and cometary orbits, for which Newton's analysis of the 1680 comet became the definitive model.

Figure 13.3: Proposition linking gravitation and Kepler’s Third Law. In this proposition from Book I, Newton analyzed the motion of a body (*b*) along an arc under a central force (F). He demonstrated the reciprocal mathematical relationship: if gravity follows a 1/r² law, then Kepler’s Third Law must hold, and vice versa, thereby providing a new physical basis for planetary motion.

The first edition of the Principia (1687) concluded with an alchemical allusion. For the 1713 second edition, Newton added a General Scholium, a disquisition on natural theology. He described a universe governed by mathematical law as evidence of an "intelligent and powerful Being," a divine Clockmaker. Famously, he stated "hypotheses non fingo" ("I feign no hypotheses") regarding the metaphysical cause of gravity, focusing instead on its mathematical description. The scholium ends with speculations on a subtle aether pervading space.

Newton's Later Life, the Calculus Dispute, and Opticks. Following the Principia, Newton experienced a severe mental breakdown in 1693, possibly due to exhaustion, chemical poisoning, or personal strife. His recovery coincided with a move into public life. After the Glorious Revolution, he represented Cambridge in Parliament and, in 1696, became Warden (later Master) of the Royal Mint, a role he held until his death. In 1703, after Robert Hooke's death, he was elected President of the Royal Society, wielding immense authority over British science. He was knighted by Queen Anne in 1705, becoming Sir Isaac Newton.

Newton notoriously abused his Royal Society presidency in the bitter priority dispute with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz over the invention of the calculus. Though both likely developed it independently, Newton orchestrated a campaign to discredit Leibniz, authoring anonymous reports that declared himself the sole inventor. Ironically, Leibniz’s notation (d for derivative, ∫ for integral) ultimately prevailed. In 1704, Newton published his other great work, Opticks, a more accessible, experiment-based book exploring the nature of light and color, Newton’s rings, and diffraction. It concluded with a series of influential Queries that speculated on light, matter, and forces, guiding future research. Like the Principia, Opticks also culminated in natural theology, arguing for God's design evident in nature.

Legacy and the Newtonian Enlightenment. Newton's influence extended far beyond science into theology and social ideology. His ideas were championed in the Boyle Lectures, such as those by Richard Bentley and William Derham, which used Newtonian science to argue for a rational, ordered universe created by God, aligning with Latitudinarian religious and political views. In this way, Newtonian cosmology became central to the prevailing social ideology of 18th-century England.

More broadly, an idealized Newton became a foundational figure for the Enlightenment. Philosophes like Voltaire saw in his work a triumph of reason over superstition. The image of a clockwork universe governed by knowable laws inspired efforts to apply rational principles to society, government, and human sciences. This Newtonian worldview contributed intellectually to the climates that produced the American and French Revolutions, metaphorically framing society as a system of equal individuals under universal laws. Alexander Pope's epitaph—"Nature, and Nature’s Laws lay hid in Night; / God said, Let Newton be! and All was Light"—captures his epoch-defining legacy as the architect of modern physics and a symbol of the age of reason.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;