The Industrial Revolution in Europe: Technological Innovation and Economic Growth Against Environmental Constraints

The history of European industry from the tenth century onward is a narrative of sustained economic development and technological advancement, consistently shaped by environmental limitations and demographic pressures. The continent's industrialization progressed concurrently with significant population growth, which perpetually threatened to outstrip available resources. Following the devastation of the Black Death, the population of England and Wales quintupled over 350 years, rising from approximately 2 million in the mid-fifteenth century to around 9 million by the close of the eighteenth century. This surge, driven by lowered mortality rates and agricultural improvements, intensified strain on resources, creating severe shortages that necessitated innovative solutions. Consequently, industrial expansion became a mechanism to sustain an enlarging population within finite ecological and economic boundaries.

A primary constraint emerged in the scarcity of land itself, a critical asset in agrarian societies like England. Land was allocated among competing uses: cropland, pasture for livestock, forestry for timber, and space for expanding urban centers as populations sought non-agricultural livelihoods. By the mid-seventeenth century, growth in towns, trade, and industry began to falter as systemic bottlenecks formed. The interconnected nature of economic activity meant a shortage in one sector could disrupt the entire system. However, the eighteenth century witnessed the successive breaking of these constraints through technological innovation, enabling the British economy to enter a period of unprecedented rapid growth. Key sectors such as iron-making, textiles, mining, and transportation were transformed by new techniques, which expanded economic capacity despite mounting demographic pressures.

Reflecting these pressures, the development of new agricultural techniques was crucial. The emergence of the Norfolk system, a set of advanced farming practices, generated the necessary agricultural surplus to support England's industrialization. This system replaced the medieval three-field system with a more productive four-field system of crop rotation. The introduction of turnips and clover allowed for the overwintering of more cattle, significantly boosting meat production. A critical component of this agricultural revolution was the enclosure movement, which converted common public land into privately owned, cultivated plots. While enclosure dramatically increased agricultural productivity, it also displaced many marginal farmers, creating a "freed" labor pool for emerging industries.

The English timber famine of the eighteenth century serves as a seminal case study in the ecological-economic tensions that propelled industrial change. The British Isles, never densely forested, saw reserves further depleted by agricultural expansion and early industrial needs. Critical industries like shipbuilding and iron smelting consumed vast quantities of wood; a single large warship required 4,000 trees, and each iron furnace annually devoured timber equivalent to four square kilometers of woodland. Furthermore, processes like bread-making, brewing, and glass production relied on charcoal, as coal's impurities, particularly sulfur, contaminated products when used directly. As scarcity intensified, timber prices skyrocketed, rising tenfold between 1500 and 1700 compared to a fivefold increase in general prices. This energy crisis precipitated a decline in British iron production by the early 1700s, creating a critical industrial bottleneck.

The pressing scarcity of wood incentivized the search for alternative fuels, particularly in the fuel-intensive iron industry. While seventeenth-century attempts to smelt iron ore with coal failed, a breakthrough came in 1709 when Quaker ironmaster Abraham Darby successfully used coke (charred coal) in the blast furnace. This innovation did not stem from scientific theory but from empirical tinkering within the artisan-engineer tradition. The gradual increase in furnace size and blast strength likely allowed higher temperatures to burn off coal's damaging impurities. Later, in 1784, inventor Henry Cort developed the puddling process, which used coal to convert pig iron into wrought iron. These advances liberated English iron production from dependence on forests, triggering a massive output increase and ushering in a new Iron Age.

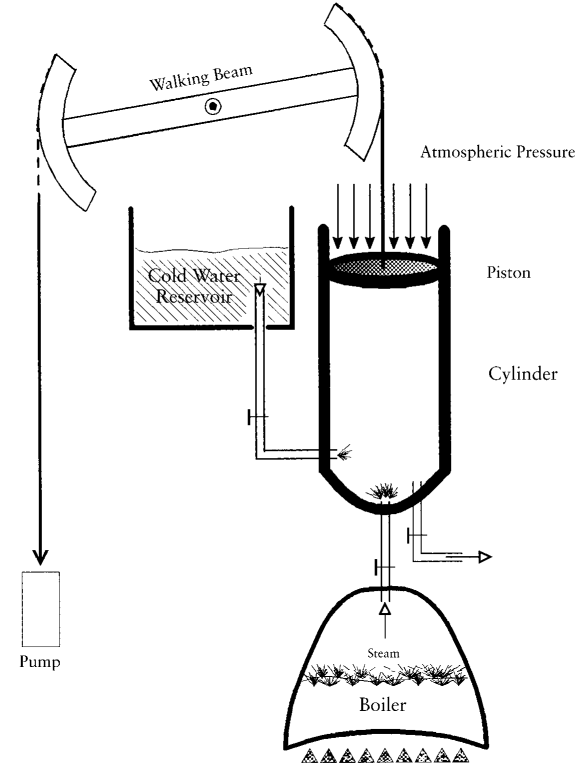

Another pivotal industry, coal mining, evolved under similar pressures of scarcity and technological challenge. As surface deposits were exhausted, mines were dug deeper, encountering prohibitive volumes of groundwater. Traditional animal-driven pumps proved inadequate, necessitating a new power source. In 1712, ironmonger Thomas Newcomen invented the first practical atmospheric steam engine to pump water from mines. This device, developed through craft intuition and trial-and-error, created a vacuum by condensing steam in a cylinder, allowing atmospheric pressure to drive a piston. Though inefficient and coal-hungry, Newcomen engines were economically viable at coal mines where fuel was cheap.

Fig. 14.1. Steam power. As mine shafts went deeper it became increasingly difficult to remove ground water. The problem was initially solved by Thomas Newcomen’s invention of the atmospheric steam engine in 1712. Because it alternatively heated and chilled the cylinder Newcomen’s engine was inherently inefficient and was only cost-effective when deployed near coal mines where fuel was inexpensive.

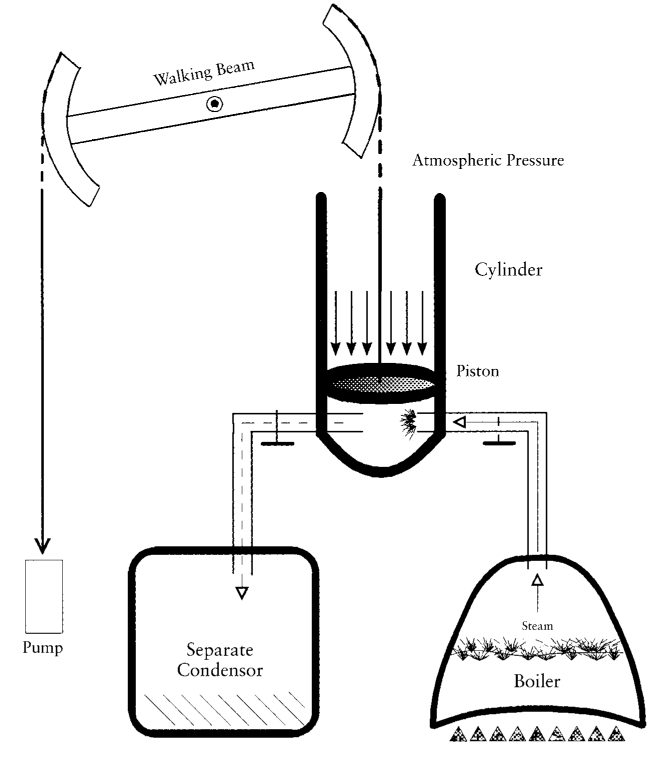

The steam engine's efficiency was dramatically improved later in the eighteenth century. While engineer John Smeaton used empirical testing to double the Newcomen engine's efficiency, James Watt introduced a radical design breakthrough. In 1765, Watt conceived the idea of a separate condenser, allowing the main cylinder to remain hot throughout the cycle, which drastically reduced coal consumption. Partnering with manufacturer Matthew Boulton, Watt successfully marketed his engines through a leasing model, charging a percentage of the customer's fuel savings. This strategy, coupled with the engine's improved efficiency, enabled its deployment beyond coal mines, powering mills in urban centers and accelerating industrial expansion.

Fig. 14.2. Watt’s steam engine. In 1765 James Watt hit upon a way to improve the efficiency of steam engines: condense the steam in a condenser separated from the main cylinder. That way the cylinder could remain hot through the entire cycle, thereby increasing efficiency and lowering operating costs. As important as Watt’s technical innovation was, the success of his steam engine depended as much on the manufacturing partnership he established with the early industrialist Matthew Boulton and the marketing strategies they devised.

Early low-pressure steam engines were large, stationary machines. The advent of compact, high-pressure designs was essential for mobility. In 1800, Englishman Richard Trevithick pioneered the high-pressure steam engine, making smaller, more powerful units feasible. Although initially met with resistance over safety concerns, this innovation paved the way for the railroad locomotive. Engineer George Stephenson unveiled his first steam locomotive in 1814, and the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1830 ignited a railroad mania. Railroad construction created a symbiotic relationship with the iron industry: cheap iron facilitated rail expansion, which in turn fueled massive demand for more iron, creating a powerful cycle of mutual growth.

The textile industry exemplified how interdependent technologies could spur rapid, self-reinforcing development. John Kay's 1733 flying shuttle sped up weaving, creating a yarn shortage that spurred spinning innovations like the spinning jenny and water frame. Mechanized spinning then outpaced weaving, until the 1785 introduction of the power loom rebalanced production. This cycle of challenge and response, later augmented by steam power, led to astronomical productivity gains; between 1764 and 1812, output per worker in the cotton industry increased two-hundredfold. The mechanization of textiles signified the full arrival of industrial civilization in England.

In conclusion, the British industrial takeoff into sustained growth from the 1780s resulted from the synergistic interaction of multiple sectors. The shift to coke-smelted iron stimulated coal mining, which required steam engines for drainage, whose need for fuel promoted railroads, which then demanded vast quantities of iron. This upward-spiraling, symbiotic process transformed society, shifting populations from rural farms to urban factories and revolutionizing transportation and construction. As with prior epochal shifts, these changes were irreversible, setting a new and enduring trajectory for global economic and social life.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;