The Classical and Baconian Sciences: A Dual Legacy of the Scientific Revolution

The exponential growth of scientific knowledge since the seventeenth century presents a significant challenge for historical analysis. The sheer scale of the modern scientific enterprise, with its monumental publication output, makes a comprehensive review of the past three centuries nearly impossible. To navigate this complexity, scholars often employ modeling, reducing intricate realities to simpler frameworks by identifying essential elements and their interactions. This approach allows us to discern two major, concurrent traditions emerging from the Scientific Revolution: the Classical sciences and the Baconian sciences.

The Classical sciences, including astronomy, mechanics, mathematics, and optics, originated in antiquity and were precisely the fields transformed during the Scientific Revolution. These disciplines were inherently theoretical and mathematical, focused on solving specific problems rather than experimental exploration. They represented specialized knowledge for trained experts, building upon foundational principles rather than empirical discovery. Their methodology was deductive, rooted in logical and mathematical reasoning from established axioms.

In contrast, the Baconian sciences developed parallel to, yet largely separate from, the Classical tradition. Named for the philosopher Sir Francis Bacon, these fields—such as the systematic study of electricity, magnetism, and heat—lacked ancient formal roots. They emerged anew as domains of empirical investigation, fueled by the intellectual ferment of the era. Characteristically qualitative and experimental, the Baconian sciences relied heavily on instruments and were only loosely guided by theory, prioritizing observation and data collection.

Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica served as the definitive exemplar for the Classical sciences, dictating problems for the community of mathematical physicists throughout the eighteenth century. Triumphs like the predicted return of Halley’s comet in 1758-59 and the international measurements of the Transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769 demonstrated the power of Newtonian mathematical science. On the European continent, mathematicians extended this work into highly technical fields like hydrodynamics and the theory of vibrating strings. This tradition achieved a conceptual zenith with Pierre-Simon Laplace’s Celestial Mechanics, a work that presented a mathematically complete, deterministic universe without divine intervention, famously leading Laplace to tell Napoleon he had "no need of that hypothesis."

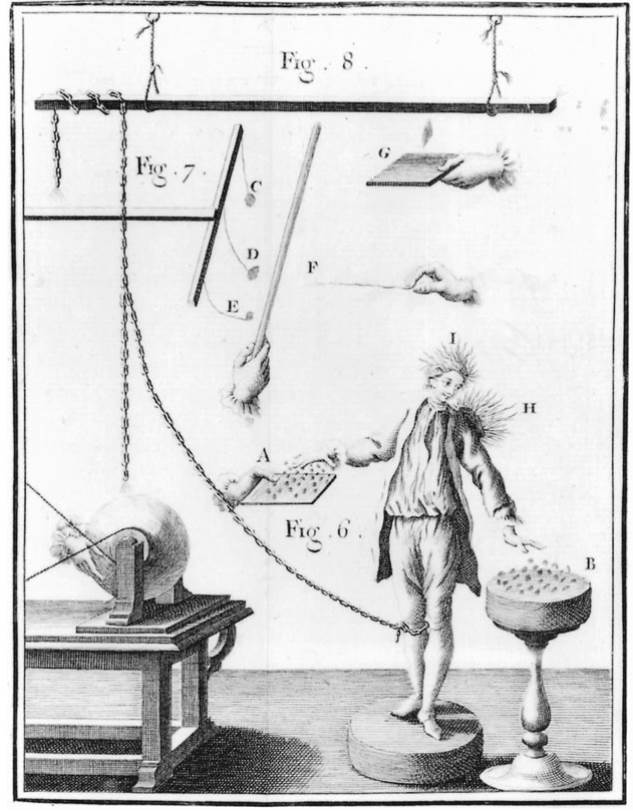

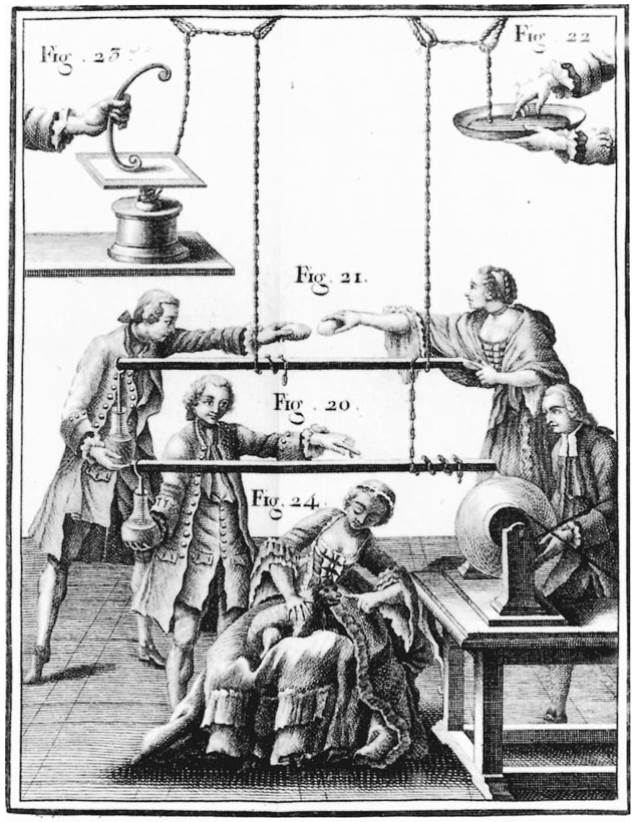

Conversely, Newton’s Opticks provided the conceptual framework for the Baconian sciences. In its queries, Newton posited various imponderable, self-repulsive ethers to explain thermal, electrical, magnetic, and optical phenomena. Eighteenth-century investigations into static electricity typify this approach, blossoming with new instruments like generators and Leyden jars. Benjamin Franklin’s kite experiment, identifying lightning as an electrical discharge, epitomized this qualitative, experimental style. Theorists, inspired by the Opticks, proposed fluid-like ethers to explain these effects, though no consensus emerged, as seen in the work of F.U.T. Aepinus on magnetism.

Fig. 15.1. Electrical equipment. The scientific investigation of static electricity blossomed in the eighteenth century aided in essential ways by the development of new experimental apparatus, such as glass or sulfur ball generators, shown here. These engravings are taken from the Abbe Nollet’s Lessons on Experimental Physics (1765). They illustrate something of the parlor-game character that often accompanied demonstrations concerning static electricity in the eighteenth century.

The Baconian model extends to fields like meteorology, natural history, botany, and geology. These were predominantly observational, relying on networks of amateur and professional data collectors using instruments like thermometers and barometers. Centralized scientific societies in London, Paris, and Uppsala became depots for global specimens, where systematists like Carolus Linnaeus and Comte de Buffon developed classification schemes. "Botanizing" became a popular pastime, reflecting the era's empirical spirit. Progress hinged on systematic data collection rather than sophisticated, theory-driven prediction.

Within this dual framework, chemistry initially appeared anomalous. With deep roots in alchemy, it underwent no restructuring during the initial Scientific Revolution. In the eighteenth century, it was governed by phlogiston theory, which posited phlogiston as a substance released during combustion. This framework coherently explained diverse processes from respiration to smelting. However, the discovery of new "airs" or gases, like Joseph Black’s "fixed air" (carbon dioxide), and anomalies like metals gaining weight during calcination, undermined the theory.

The Chemical Revolution was catalyzed by Antoine Lavoisier. Through meticulous quantitative experiments, he demonstrated that combustion involved a component of air being absorbed, not a substance released. He identified this component as oxygen. Lavoisier's systematic approach, including a new chemical nomenclature (e.g., hydrogen, sulfate) and his 1789 textbook Elementary Treatise of Chemistry, rhetorically and practically dismantled phlogiston chemistry. By banishing phlogiston, he redefined the theoretical core of the science.

A key feature of Lavoisier's system was his separation of chemical from thermal phenomena. To explain heat, he introduced a new imponderable fluid, caloric, an elastic ether that permeated matter. By invoking caloric, Lavoisier ultimately normalized chemistry within the Newtonian framework of ethereal fluids suggested by the Opticks. Thus, chemistry resolved its anomalous position, finding its place within the broader model of interacting Classical and Baconian scientific traditions that characterized post-Revolutionary science.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;