The Global Spread of Industrialization in the 19th and 20th Centuries: Impacts on Society, War, and Colonialism

Meta Description: Explore the history of industrialization's global spread from its 19th-century origins. This analysis covers its uneven progress, core technologies like steel, the industrialization of war, and its profound link to European colonialism, with case studies on India, Russia, and Japan.

The transformative force of industrialization, which originated haphazardly in 18th-century English coal, iron, and textile industries, coalesced into a dominant new mode of production and social organization during the 19th century. While its global impact was still limited around 1800, industrialization subsequently spread from England in successive waves, fundamentally altering the world by 1900. This profound technological and social metamorphosis occurred unevenly across different regions and in distinct stages, continuing to the present day. Furthermore, unlike earlier societal revolutions, industrialization unfolded with unprecedented and rapid velocity, reshaping human existence at an accelerated pace.

The initial eruption of industrialization on a world scale commenced between 1820 and 1840, first affecting Belgium, Germany, France, and the United States. While nations like Germany achieved a 50 percent urban population by 1900, the spread across Europe and North America remained irregular, forming a core of industrial civilization. Notably, vast areas including Eastern Europe, parts of Ireland, the American South, and most of the world remained predominantly agrarian well into the 20th century. This pattern established a deep global economic divide between industrialized and non-industrialized regions that persists in various forms today.

Although national variations existed, the process consistently centered on core industries: iron, textiles, railroads, and later, electrification. As industrial intensification advanced, it revolutionized construction, food processing, and domestic work, while new science-based sectors emerged from breakthroughs in chemistry and electricity. An expanding service sector, employing many women as clerks, teachers, and telephone operators, complemented these industries. Concurrently, higher education adapted through new university programs in engineering, nursing, and architecture, which increasingly relied on foundational scientific principles.

By the 1870s, industrialization had transformed Europe and the United States into globally dominant powers, fueling a new era of colonial imperialism. This period saw the solidification of British rule in India, French empire-building in Africa and Southeast Asia, the Russian expansion across Asia, and the European "Scramble for Africa." This dominance stemmed primarily from a Western monopoly on industrial production and technology, which other regions lacked the resources or technical capability to match. Consequently, by 1914, the empires of Western powers controlled approximately 84 percent of the globe.

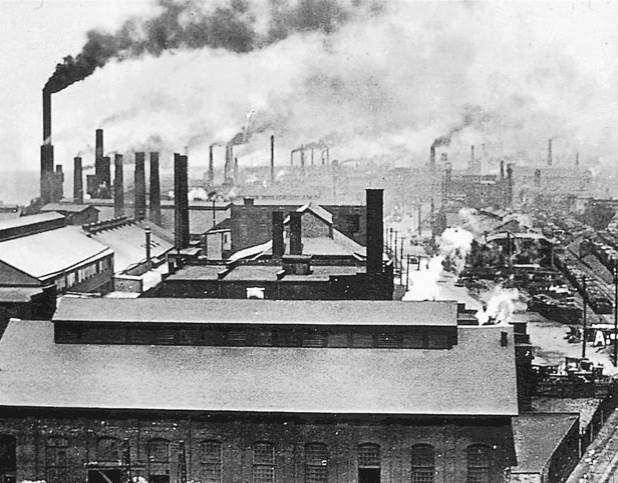

Fig. 15.3. Industrial pollution. In developed societies today, scenes such as this one from the 1920s are less common due to increased emissions controls and environmental concerns. However, such regulations remain a significant challenge in developing regions where the costs are harder to meet. A central question for the future is whether industrial civilization can achieve a sustainable balance with the planet's ecology.

The spread of industrialization is inextricably linked to European colonialism and imperialism, which fueled it by securing cheap raw materials and creating captive markets for manufactured goods. India exemplifies this dynamic, undergoing deliberate deindustrialization under British rule after 1858. Once a world leader in textile export and shipbuilding, India was transformed into a net importer of British goods and a supplier of raw materials. Infrastructure like railroads and telegraphs, introduced rapidly after 1853, served primarily as instruments of colonial control and resource extraction rather than catalysts for indigenous industrial growth, leading to increased poverty and technological displacement.

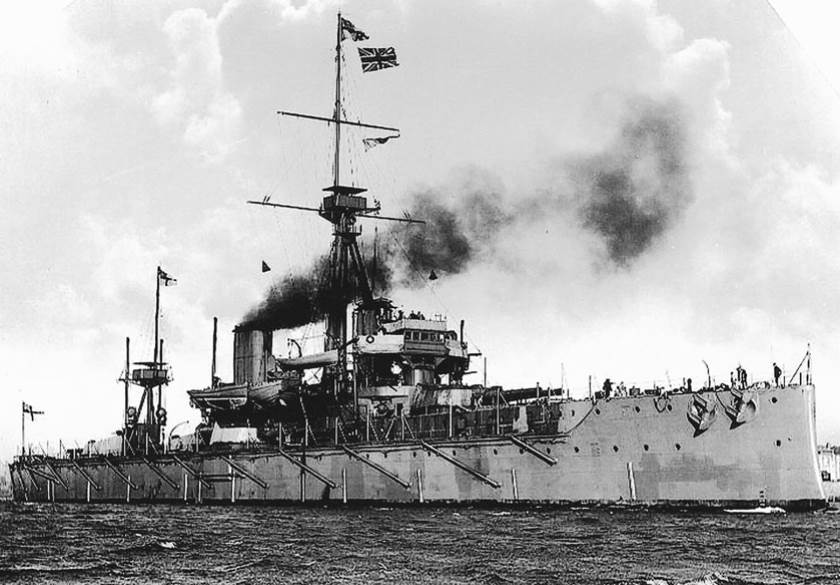

A constellation of new technologies, particularly the industrialization of war, underpinned continued European dominance. The development of the steamship, especially as a military vessel, allowed for the projection of power deep inland via river systems and secured victories like those in the Opium Wars in China. This evolution culminated in steel-hulled battleships like the HMS Dreadnought, launched in 1906, which could strike coastal targets from great distances. These advancements meant that only nations with steel production capabilities could compete in this new era of global power politics.

Central to this was the innovation of steel production. The Bessemer process, invented in the 1840s, revolutionized metallurgy by allowing the inexpensive mass production of wrought iron, symbolized by structures like the Eiffel Tower (1889). This short-lived Age of Wrought Iron was soon superseded by the Age of Steel, as methods to produce true steel—an alloy with ideal malleability and tensile strength—were perfected. Steel, the material of the Empire State Building (1930), became the raw backbone of industrial society and modern warfare.

Fig. 15.4. The Industrialization of War. Launched in 1906, the HMS Dreadnought was the most formidable armored battleship of its day. With a main battery of ten 12-inch guns, driven by a steam turbine power-plant, and capable of a speed of 21 knots, this revolutionary vessel surpassed every previous warship in design and military capability and was testimony to the might of industrial civilization in Britain.

Steel fueled a relentless European arms race, leading to machine guns, bolt-action rifles, submarines, and the doctrine of gunboat diplomacy. The American Civil War previewed industrialized land warfare using railroads, while World War I, known as the "chemists' war," showcased total dependence on heavy industry, tanks, and poison gas. Military technologies and industrial development became locked in a cycle of mutual stimulation, with innovations in the interwar period, like warplanes and motorized vehicles, further strengthening imperial control and competition.

Industrialization extended eastward with the case of Russia, which relied on foreign expertise and capital to build its economy. Railroad construction, exploding from 700 miles in 1860 to over 43,000 by 1913, facilitated both industrial growth and Russia's own imperial expansion across Asia via the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Following the 1917 Russian Revolution, the Soviet Union achieved rapid, state-driven industrialization at great human cost, emerging by the late 1940s as the world's second-largest manufacturing economy, distinct for its isolation from the Western industrial system.

Japan became the first nation to break the European industrial monopoly after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Maintaining political independence, Japan pursued state-planned development through its Ministry of Industry, focusing on railroads, shipbuilding, and mechanized silk production. Unique features included a high proportion of women in the workforce and cultural paternalism that eased the social transition. By the early 20th century, Japan itself became an imperial power, signaling the global diffusion of industrial might and setting the stage for the truly multinational industrial landscape that emerged after World War II. This global spread fundamentally enabled the modern merger of science and technology within the framework of industrial civilization.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;