Historical Development of Evolutionary Thought Before Darwin: From Natural Theology to Geological Evidence

A consensus, consistent with Galileo Galilei's advice, now holds that scientific investigation takes precedence over biblical authority in the study of nature, dispelling the myth of inherent conflict between science and religion. Notably, the Scientific Revolution of the seventeenth century often strengthened ties between science and the Christian worldview. A key development was the rise of natural theology, particularly in England, which sought insight into the divine plan by examining God's handiwork in nature. This conviction that studying apparent design revealed the Great Designer stimulated scientific research, as seen in works like John Ray's Wisdom of God in the Creation (1691), aiming to reconcile genesis with geology.

Throughout the eighteenth century, empirical research in botany, natural history, and geology expanded dramatically. The tradition of natural theology remained central, especially in English science, culminating in William Paley's influential 1802 work, Natural Theology. Paley's argument from design, using the analogy of a watch and a watchmaker, posited that biological complexity implied a Creator. This view, which influenced the young Charles Darwin, was further propagated by the eight Bridgewater Treatises (1830s), scientific studies designed to showcase divine wisdom in creation.

Order was brought to burgeoning biological knowledge by Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus. His binomial system of classification, which assigns each organism a genus and species name, organized life according to what he saw as God's plan. While his system initially supported the fixity of species, Linnaeus later speculated that species and varieties might be "daughters of time," hinting at change. Prior to Darwin, several naturalists explored the transformation of species. French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, proposed that species degenerated from more robust ancestors, though he lacked a mechanism and later recanted under religious pressure.

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck provided a proposed mechanism with his theory of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. He argued organisms modify themselves through use and disuse, passing these adaptations to offspring, thus creating new species over time. While empirically discredited, Lamarckian inheritance was influential, offering a purposeful element to evolution. Similarly, Erasmus Darwin, Charles Darwin's grandfather, espoused evolutionary ideas in poetic form, suggesting life arose spontaneously and that useful inherited traits slowly accumulate.

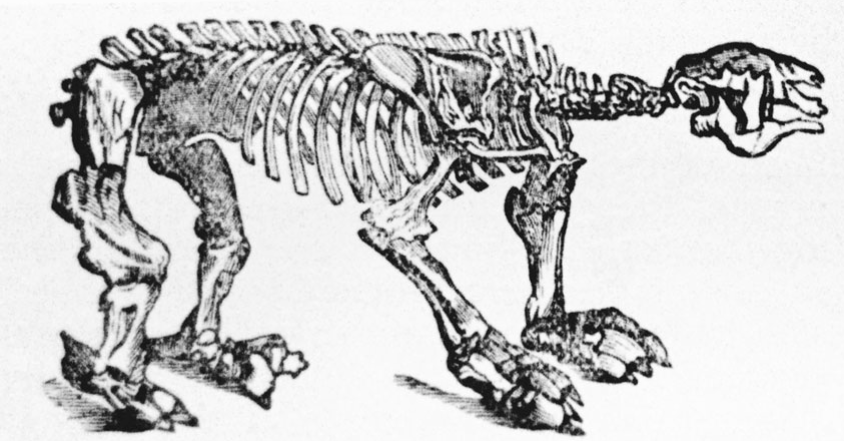

These new ideas intersected with older concepts like the Great Chain of Being, an organic continuum from simple to complex life. Both creationist and evolutionary theories embraced this continuum without missing links. However, they diverged sharply on the age of the earth; evolutionary theory required vast timescales for incremental changes, challenging the biblical chronology. By the late eighteenth century, evidence from geological strata and the fossil record became irreconcilable with a young Earth. Marine fossils found at high altitudes suggested immense, slow upheavals, while the discovery of large vertebrate fossils confirmed biological extinction and a lost prehistoric world by 1830.

To reconcile new evidence with tradition, catastrophism, developed by French naturalist Baron Georges Cuvier, proposed that Earth's history was punctuated by brief, catastrophic events like floods. This preserved a relatively short timeline and admitted extinction and progressive change without violating the fixity of species. Conversely, uniformitarianism, advanced by James Hutton and later Charles Lyell, argued that slow, continuous processes observed today shaped Earth over limitless time. Lyell's Principles of Geology (1830-33) provided a vast temporal framework but he rejected species transformation, leaving the mechanism for biological change unresolved.

Fig. 16.1. The Megatherium. In the first decades of the nineteenth century the discovery and reconstruction of the fossils of extinct large animals like the Megatherium, a giant ground sloth, revealed a "lost world of prehistory" and heightened the problem of how to account for apparent biological change over time. This mounting paleontological evidence created the intellectual environment that awaited a unifying explanation, which would eventually be provided by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace's theory of evolution by natural selection.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;