The Historical Integration of Science and Industry: From 19th Century Applied Science to Modern Technology

The historical unification of science and industry, along with their respective cultures, fundamentally commenced in the nineteenth century. A central thesis posits a historically limited scope for practically oriented applied science prior to this period. While early states patronized useful knowledge for administration, and post-Medieval Europe saw gradual state support for sciences like cartography, a significant intellectual and sociological separation persisted. A key measure of this divide was the educational chasm in Europe between university-trained scientists and the craft-trained engineers and artisans.

The Industrial Revolution in eighteenth-century England began bridging the worlds of science and practical technology, yet technology was not merely applied science. The nineteenth century introduced pivotal novelties that recast the ancient separation originating in Hellenic Greece, forging firm connections between theoretical science and large-scale industry. While many domains remained distinct, the new dimensions of applied science emerging from industrialization represented a profound historical departure, solidifying globally in subsequent centuries.

One transformative field was the new science of current electricity, which spawned industries like the telegraph. Following Michael Faraday’s 1831 discovery of electromagnetic induction, scientist Charles Wheatstone and a collaborator invented the first electric telegraph in 1837. Efforts by various scientists and inventors, spurred by the telegraph's utility for railroads, culminated in Samuel F. B. Morse’s 1837 patented system and his famous code, field-tested in 1844. Rapid global deployment, including the first trans-Atlantic cable (1857-58) and transcontinental line in North America (1861), precipitated a communications revolution.

However, telegraphy's development required solving myriad technical, commercial, and social problems unrelated to contemporary scientific theory, illustrating that science-based technology involves creating complex technological systems. This complexity makes it misleading to view such systems as simple applications of scientific knowledge. The emergence of the telephone, invented by Alexander Graham Bell in 1876, further exemplified this principle, requiring an evolving infrastructure of wires, exchanges, operators, and social adaptations before challenging the telegraph.

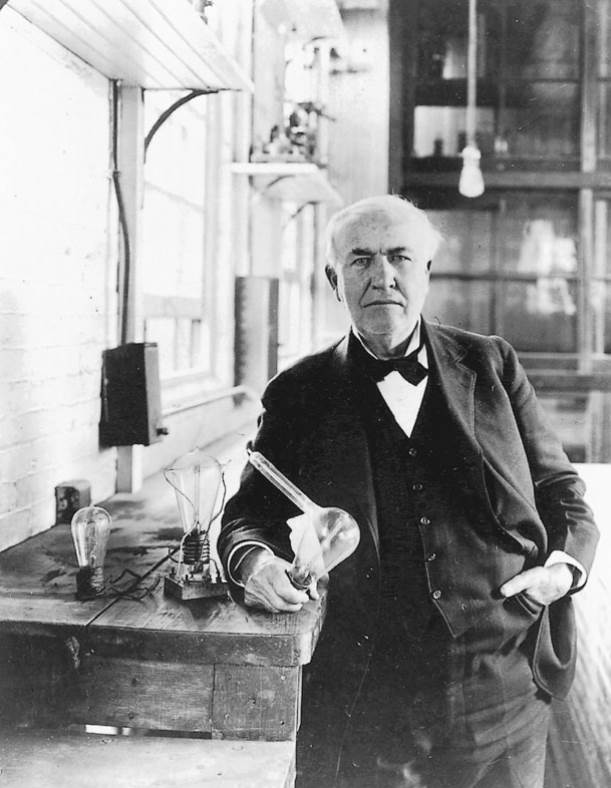

Similarly, the electric lighting industry, derived from prior electrical science, required a vast systemic infrastructure beyond the incandescent light bulb invented by Thomas Alva Edison and Joseph Swan in 1879. Establishing a practical industry necessitated generators, power distribution networks, meters, and billing methods. This underscores an analytical distinction in applied science between utilizing established, "boiled down" science and applying cutting-edge theoretical research.

Fig. 15.5. Invention without theory. Thomas Edison was a prolific inventor (with more than 1,000 patents) who had little education or theoretical knowledge. His ability to tap “boiled down” science and his organizational skills in institutionalizing invention in his laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, proved essential to his success.

A prime instance of cutting-edge theory application was radio communications. After Heinrich Hertz demonstrated radio waves in 1887 to confirm Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism, Guglielmo Marconi exploited them for practical wireless telegraphy by 1894. Marconi's technical achievements, leading to the first trans-Atlantic signal in 1901, blurred the line between science and technology so profoundly he received the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics. This case also highlights the unpredictability of research outcomes, as Marconi's initial goal of ship-to-shore communications unforeseeably led to broadcast radio.

The growth of applied science extended beyond physics into fields like scientific medicine. The 1840s introduction of anesthesia and Joseph Lister’s 1860s antiseptic measures were monumental advances. Furthermore, the germ theory of disease led Louis Pasteur to studies of fermentation, yielding the practical process of pasteurization for dairy, wine, and beer industries. His work on silkworm diseases and development of inoculations against anthrax and rabies marked the advent of truly scientific medicine.

Chemistry was another domain where science yielded major industrial applications. The European dye industry, initially a craft with no scientific contact, was revolutionized in 1856 when English chemist William Perkin discovered the first synthetic dye. The economic value of synthetic dyes derived from coal tar became crucial for textiles. After Germany's uniform patent code in 1876, competition shifted to research and development, fostering the new institution of the industrial research laboratory. The Friedrich Bayer Company, for instance, hired its first chemistry Ph.D. in 1874 and employed 104 staff scientists by 1896.

The applied research style at Bayer emphasized close university-industry collaboration. Universities conducted fundamental research, while industrial labs performed empirical testing, as evidenced by Bayer testing 2,378 colors in 1896 to market only 37. This demonstrates that applied science often involved systematic trial and error by scientists, far from the simplistic model of directly translating theory into practice.

The research laboratory model proliferated widely, with early examples like Edison’s Menlo Park lab (1876) and later ones including General Electric (1901), DuPont (1902), and Bell Labs (1911). These labs institutionalized the "invention of invention," though they typically focused on developing existing technologies and securing patents rather than producing radically new inventions, which sometimes still emerged from independent innovators.

Concurrently, broader imperial and exploratory endeavors, like British global surveys for mapping and specimen collection, yielded completely unexpected theoretical advances, most notably the theory of evolution. This underscores how the intertwined trajectories of science, technology, and society in the nineteenth century created a new paradigm for knowledge and its application, whose legacy definitively shaped the modern world.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;