The Second Scientific Revolution: Unification and Mathematization in 19th-Century Physics

A profound intellectual transformation, known as the Second Scientific Revolution, began at the turn of the nineteenth century. This era was defined by two interconnected trends: the rigorous mathematization of previously qualitative Baconian sciences and the conceptual unification of these with the Classical sciences. These processes merged separate scientific traditions into a new synthesis, ultimately forming the modern discipline of physics. As this revolution progressed, a coherent Classical World View emerged, promising a complete understanding of the physical universe through a single set of universal laws, suggesting to some the nearing end of fundamental physics.

The pattern of mathematization and unification is evident across numerous nineteenth-century research specialties. Developments in electricity and their links to magnetism and chemistry provide a compelling case study. While eighteenth-century electrical science dealt only with static electricity, Luigi Galvani’s 1780s experiments with frogs' legs inadvertently revealed current electricity. His compatriot, Alessandro Volta, built upon this discovery, inventing the pile (battery) in 1800, which generated a continuous electrical current. This chemically-based instrument demonstrated a fundamental connection between electricity and chemistry, a link solidified when Humphry Davy used electrolysis to discover new elements like sodium and potassium, leading to an electrical theory of chemical combination.

These electrochemical discoveries supported the revival of atomistic interpretations. While Antoine Lavoisier defined elements as the final products of chemical analysis, John Dalton in 1803 noted that elements combine in ratios of small integers. This observation led him to propose chemical atoms as discrete, indivisible particles, establishing a definitive link with the philosophical atomism of the seventeenth century. Although not immediately universally accepted, Daltonian atomism became a cornerstone of chemistry by mid-century, providing a particulate basis for understanding matter.

Simultaneously, the suspected unity between electricity and magnetism was conclusively demonstrated in 1820 by Hans Christian Oersted. He accidentally discovered that an electric current could deflect a compass needle, revealing the magnetic effect of electricity and unveiling the principle behind the electric motor. This pivotal finding spurred rapid developments, including the invention of the electromagnet and the observation of forces between current-carrying wires.

These investigations culminated in 1831 with Michael Faraday’s discovery of electromagnetic induction—generating electricity from magnetism—by moving a magnet through a coil of wire. Beyond its technical application in the dynamo (electric generator), Faraday's work philosophically proved the deep interconnection between electricity, magnetism, and motion. This established that any two of these three natural forces could be used to produce the third, reinforcing the theme of unification.

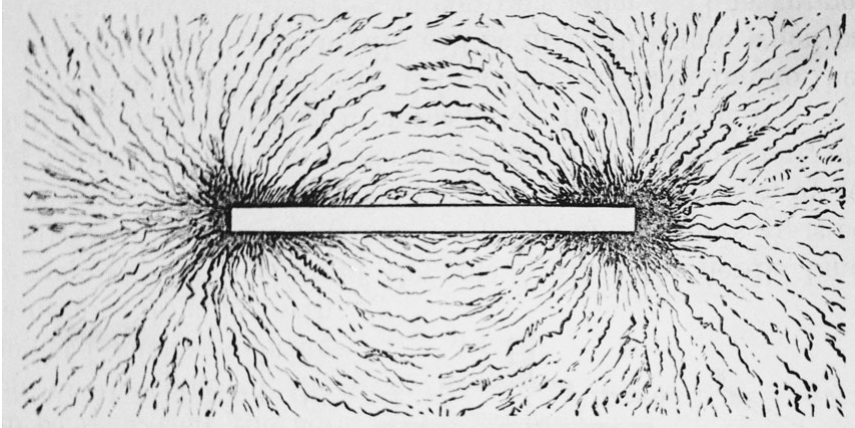

Fig. 15.2. Faraday’s lines of force. Michael Faraday postulated that lines of force occur in a field surrounding a magnet. He illustrated this proposition by observing patterns that iron filings form in the space around a magnet.

Faraday's conceptualizations were profoundly influential. Lacking formal mathematics, he visualized electromagnetic effects as lines of force within a field, shifting scientific focus from the wires and magnets themselves to the surrounding space and initiating field theory. This period also witnessed an incipient merger of scientific theory and technology, as electrical science and new devices like motors and generators advanced synergistically.

Parallel revolutions occurred in optics. The eighteenth-century dominance of Newton’s particle theory gave way to wave theory through the work of Thomas Young and Augustin Fresnel. Young proposed light as a longitudinal wave in 1800, while Fresnel's superior transverse wave model accounted for diffraction and interference phenomena. His dramatic experimental confirmation of a predicted bright spot in a shadow won the Paris Academy prize in 1819, securing the wave theory's acceptance.

The acceptance of the wave theory of light necessitated a medium for propagation, leading to the postulate of a universal, all-pervasive luminiferous ether. This concept marked a key unification, as the many subtle fluids of earlier Baconian science collapsed into this single cosmic substrate. New research areas like spectroscopy emerged, revealing unexpected ties between light and chemistry through distinctive elemental spectra.

The science of heat underwent similar conceptual innovation. Moving beyond Lavoisier’s material caloric, Joseph Fourier mathematicized heat flow, while Sadi Carnot’s 1824 analysis of the steam engine and the Carnot cycle provided a paradigm of technology driving scientific inquiry. This culminated in the creation of thermodynamics, a new discipline unifying heat and motion.

The most profound development was the formulation of the laws of thermodynamics. The first law (conservation of energy), independently enunciated in the 1840s, posited that forces like heat, light, electricity, and motion were interconvertible forms of a conserved entity—energy. James Prescott Joule quantified the mechanical equivalent of heat. Later, Rudolf Clausius formulated the second law of thermodynamics, stating that in a closed system, energy differences even out irreversibly, introducing the seminal concept of the arrow of time and implying a potential universal heat death.

For the physical sciences, the Classical World View or Classical Synthesis coalesced in the late nineteenth century, offering a comprehensive and unified picture of reality. Its unity crystallized around James Clerk Maxwell, who mathematicized Faraday's fields into the elegant Maxwell’s equations. These equations described electromagnetic waves traveling at the speed of light, thereby unifying electromagnetism and optics. Heinrich Hertz’s 1887-88 experimental detection of radio waves confirmed this synthesis spectacularly.

This worldview rested on absolute space and time and posited three fundamental entities: matter, the ether, and energy. Matter consisted of immutable, identical atoms, as systematized by D. I. Mendeleev’s periodic table. These atoms moved under gravitational force and possessed mechanical energy, their motion analyzed by statistical mechanics. The ether served as the medium for radiant energy (light, heat, electromagnetic waves), all interconnected and governed by thermodynamics.

While the Classical World View represented a powerful, mathematically exact synthesis, it was not without dissent or unresolved issues. Lively debates persisted about its representation of underlying reality. Furthermore, unexpected discoveries at century's end, like radioactivity, quickly dispelled any overconfident sense of closure, setting the stage for the twentieth-century revolutions led by Albert Einstein.

Concurrently, the life sciences were revolutionized. The term biology itself was coined in 1802. Cell theory, established by Matthias Schleiden and Theodor Schwann in the 1830s, identified the cell as life's basic unit. Claude Bernard pioneered experimental physiology, and the germ theory of disease advanced by Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur in the 1870s transformed medicine, decisively displacing humoral and environmental explanations for illness and cementing the authority of laboratory-based science.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;