The Nexus of Science and Craft: Reassessing the Theoretical Foundations of the Industrial Revolution

The technical innovations underpinning the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were primarily the work of craftsmen, artisans, and engineers, most lacking a university education and achieving their breakthroughs without direct recourse to scientific theory. A persistent historical legend, however, suggested these inventors were counseled by luminaries of the Scientific Revolution, such as claims that Thomas Newcomen was instructed by Robert Hooke or that James Watt applied Joseph Black’s theory of latent heat. Modern historical research has discredited these myths, demonstrating instead that scientific analysis often followed technological invention. For instance, the French physicist Sadi Carnot produced the first scientific study of steam engines in 1824, long after they were commonplace, illustrating how technical developments frequently provoked subsequent theoretical advances.

This misconception, that technology is inherently applied science, gained traction despite being only partially true even in modern contexts and almost never the case during the early Industrial Revolution. Science nevertheless played a crucial social and ideological role, as scientific culture permeated European society through learned societies, academies, and public lectures, promoting a worldview valuing reason and the useful exploitation of nature. While natural theology strengthened the concord between science and religion, the scientific enterprise itself remained largely divorced from practical applications. Therefore, although the rational outlook of science was culturally important, technologists and engineers proceeded without tapping into formal bodies of scientific knowledge, operating instead within traditional craft-based paradigms.

Notably, several eminent craftsmen established social contacts with the scientific world, as seen in England where engineers James Watt and John Smeaton and potter Josiah Wedgwood became Fellows of the Royal Society. Their published contributions to the Society's Philosophical Transactions, however, bore little relation to their industrial work; Watt wrote on phlogiston chemistry and Wedgwood's research led to a pyrometer, but his famed Wedgwood ceramic ware preceded his chemical interests. Smeaton empirically demonstrated the superior efficiency of overshot waterwheels over undershot ones, applying this insight in his projects, yet this was not derived from theoretical principle and had limited broader industrial impact. These examples underscore that their forays into science were consequences, not causes, of their technical careers.

Formal technical education was nascent, as evidenced by the 1742 founding of the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich to train artillery and engineering officers in subjects like fluxions (Newtonian calculus). However, graduates lacked craft experience, rendering them ineffective as working engineers, leaving industrialization to be driven by unschooled civilian engineers. This period did see a sociological shift, with technology beginning to align more closely with the perceived rational methods of science, yet a significant gulf remained between practical application and theoretical research. An episode from Watt's career highlights this divide: his attempt to commercially exploit Claude Louis Berthollet's chlorine bleaching process was met by the chemist's ethos of pure science, with Berthollet asserting that love of science precluded the need for wealth.

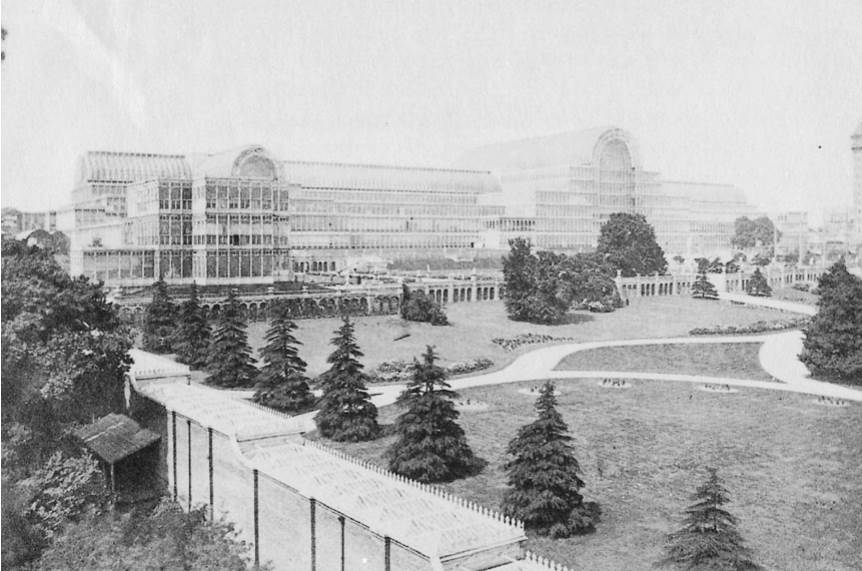

Fig. 14.3. The Industrial Age. The Crystal Palace, erected in 1851 for an international exposition in London, was a splendid cast-iron and glass structure that heralded the new industrial era.

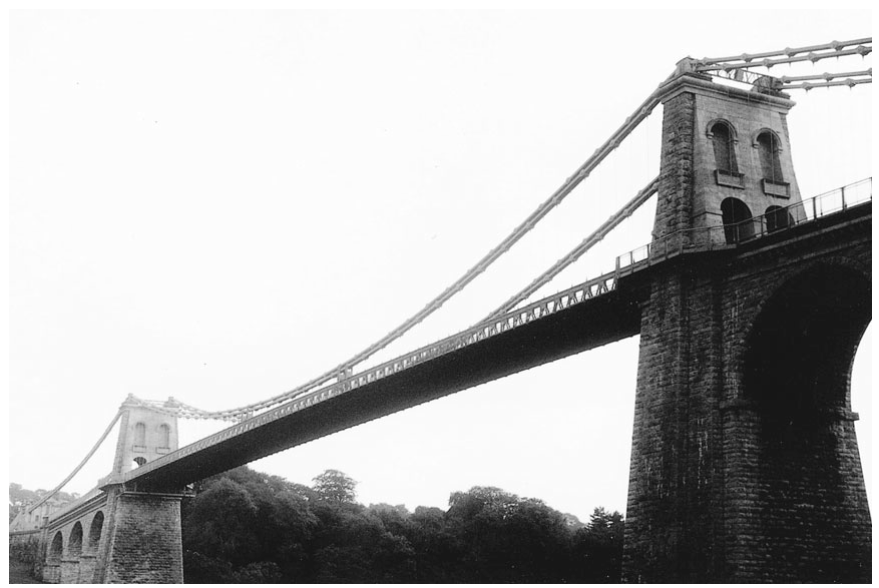

A telling failure to bridge this gap occurred around 1800 regarding a proposal by engineer Thomas Telford for a 600-foot single cast-iron arch bridge over the Thames. With no established theory of structures or engineering science professorships, Parliament consulted separate committees of theoretical scientists and practical builders. The exercise proved futile, exposing the disconnect between abstract mathematics and practical construction. The Astronomer Royal's suggestions were derided as practically useless, while a geometry professor calculated the bridge's length to ten-millionths of an inch—a theoretical precision irrelevant to real-world engineering. As Cambridge's Isaac Milner noted, theory without practical knowledge yielded elegant but unsafe calculations.

Fig. 14.4. Thomas Telford’s iron bridge across the Menai Straits (completed 1824). In the eighteenth century, iron was adapted to structural engineering. The cast-iron arch bridge was followed by wrought-iron suspension bridges and wrought- iron tubular bridges. Organizational and managerial skills proved no less important for the success of bridge building than the technical mastery of iron as a construction material.

Theoreticians like John Playfair conceded that mechanics, even using higher geometry, could not yet handle such complex designs, leaving them to the intuition of craftsmen. It would take another half-century for works like John Rankine's Manual of Applied Mechanics to chart a path toward genuine engineering sciences. Consequently, while the Scientific Revolution provided a cultural framework, it did not supply direct theoretical tools for invention. Governments held Baconian hopes for science's utility, but the technical dimension of industrialization was crafted by unschooled ingenuity, absent the textbooks, university programs, professional societies, physical constants, and research laboratories that would later define applied science.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;