The Scientific Revolution and the Rise of Experimental Method in the 16th-17th Centuries

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe were characterized by intense intellectual conflict between competing visions of natural philosophy. Traditional Aristotelianism and various occult traditions contended with the emerging "new science" or mechanical philosophy. This new paradigm revived ancient atomistic and corpuscularian doctrines, proposing that all natural phenomena could be explained through mechanical explanations involving only matter, motion, and force. Crucially, it championed experimental verification and the open communication of knowledge, contrasting sharply with the secretive nature of occult learning. By 1700, institutionalized within new academies and societies, this open system had largely triumphed, appealing to state powers wary of the politically destabilizing potential of secretive, "closed" doctrinal systems.

Proponents of the mechanical philosophy, such as René Descartes, vigorously defended it against accusations of atheism and determinism. Descartes addressed these concerns through his rigorous mind-body dualism, which strategically cordoned off the realm of spirit and religion from the mechanical workings of nature. This separation allowed scientific inquiry to proceed without directly challenging theological orthodoxy. Furthermore, the integration of natural theology—using nature to argue for God’s existence and attributes—became a cornerstone of influential syntheses like Newtonian science. As a standard operating principle, new scientific institutions like the Royal Society formally excluded discussions of politics and religion, directing research squarely at understanding the natural world.

The period witnessed an unprecedented proliferation of experimental science, though practitioners employed diverse methodologies without consensus on a single "experimental method." William Gilbert experimented with magnets, Galileo Galilei with inclined planes, Evangelista Torricelli with mercury tubes, and Robert Boyle with air pumps. William Harvey conducted systematic vivisections, while Isaac Newton employed prisms in his optics research. Notably, the formal hypothetico-deductive method—posing a hypothesis, testing it via experiment, and accepting or rejecting it based on the outcome—was not the dominant model. Instead, experiments served varied purposes: for confirmation (Galileo), as crucial proofs (Newton), or as exploratory tools. Thought experiments, like Galileo imagining the view from the Moon, also constituted a legitimate form of scientific reasoning, underscoring that experiment was a historically contingent and evolving practice.

The roots of this experimental culture were heterogeneous. Alchemy provided one significant pathway, emphasizing hands-on manipulation of matter. Furthermore, the popular Renaissance "books of secrets"—practical handbooks containing empirical recipes for crafts and trades—fostered a culture of practical testing. Groups like Giambattista Della Porta's Academy of Secrets experimented not to test abstract theories but to verify the efficacy of these practical techniques. This model framed experimentation as a noble "hunt" for nature's secrets, with successful discoverers potentially gaining prestige and patronage, blending utility with intellectual pursuit.

Francis Bacon articulated a influential, multifaceted philosophy of experiment within his broader program of inductive reasoning. He advocated for "experiments of fruit" aimed at generating useful inventions and for "experiments of light" designed to illuminate fundamental truths about nature. Baconian experiments, such as observing rotting meat or testing preservation with snow, were often fact-gathering missions to feed later inductive analysis, not hypothesis tests. However, his vision also included a role for more targeted, theory-informed experiments. In stark contrast, René Descartes's rationalist, deductive approach from first principles led him to largely dismiss Baconian induction and downplay experiment's role. For Descartes, experiment was only marginally useful for deciding between plausible theoretical alternatives deduced from mechanical causes, not for discovering those causes initially.

As the century progressed, experiment evolved into a refined tool for theory testing and advancing scientific discourse. Newton's "crucial experiment" with the prism, Robert Hooke's derivation of Hooke’s Law from spring tests, and Boyle's pneumatic work exemplify this maturation. This rising emphasis made the scientific enterprise increasingly instrument-based and technology-dependent. Investigators relied on telescopes, microscopes, thermometers, barometers, and air pumps, which extended the senses and created new phenomena to study. This demand, in turn, fostered a new profession of skilled instrument makers. The use of such technologies transformed the very process of knowledge production, making it dependent on complex, man-made apparatus.

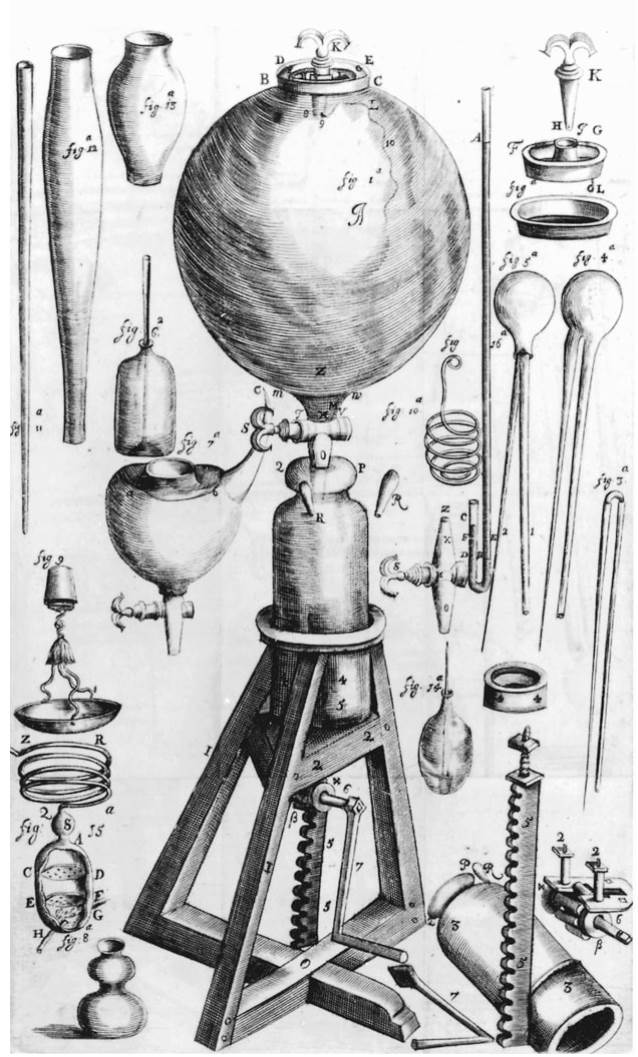

Fig. 13.4. The air pump. This invention led to many experiments in which objects were observed under conditions of a near vacuum. The realities of such experiments were more complex and difficult than apparent in the reported results.

The air pump or vacuum pump, invented by Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke (1658-59), serves as a premier case study. It created a novel "experimental space"—the evacuated receiver—and was used by Boyle to discover the relationship between the pressure and volume of a gas (Boyle’s Law). While textbook accounts simplify this discovery, historical research reveals profound social and instrumental complexities. Early pumps were rare, expensive, leaky, and difficult to operate, making experimental replication elusive. Demonstrations within venues like the Royal Society became performative acts where an operator’s skill and social credibility were paramount. Claims were contested, and knowledge spread via written reports that allowed distant readers to become "virtual witnesses." Thus, establishing a matter of fact like Boyle’s Law involved intricate negotiations, highlighting the inherently social nature of scientific knowledge production in the new, experimental paradigm.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;