Neolithic Science and Astronomy: Stonehenge as a Monument to Prehistoric Knowledge

The Neolithic revolution, a fundamental techno-economic process transitioning societies to agriculture, unfolded without reliance on formal science. Examining the relationship between technology and science in this era, pottery exemplifies a craft developed through practical necessity and accumulated craft knowledge, not theoretical science. Neolithic potters possessed extensive empirical understanding of clay and fire behavior, yet their work proceeded without a systematic science of materials or deliberate theory application. To suggest these crafts required higher learning underestimates their autonomous technological ingenuity.

Significant scientific activity in the Neolithic period is most evident in the field of Neolithic astronomy. Substantial archaeological evidence confirms that many prehistoric peoples conducted systematic celestial observations, particularly tracking the sun and moon. They constructed astronomically aligned monuments functioning as sophisticated seasonal calendars. This practice represents not merely the prehistory of science but constitutes science in prehistory, demonstrating methodical investigation of natural phenomena.

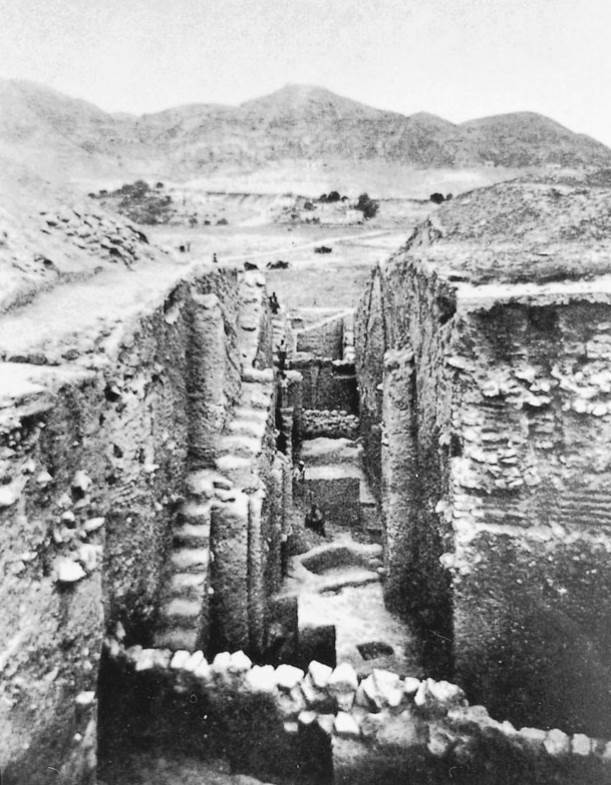

Fig. 2.2. Jericho. Neolithic farming produced a surplus that needed to be stored and defended. Even in its early phases, the Neolithic settlement of Jericho surrounded itself with massive walls and towers, as shown in this archaeological dig.

The Stonehenge monument on England's Salisbury Plain provides the most profound case study. Radiocarbon dating reveals its construction occurred in three major phases over 1,600 years, from 3100 BCE to 1500 BCE. The name Stonehenge, meaning "hanging stones," reflects the immense technological feat of transporting, working, and erecting its massive stones, a testament to Neolithic engineering capabilities in prehistoric Britain.

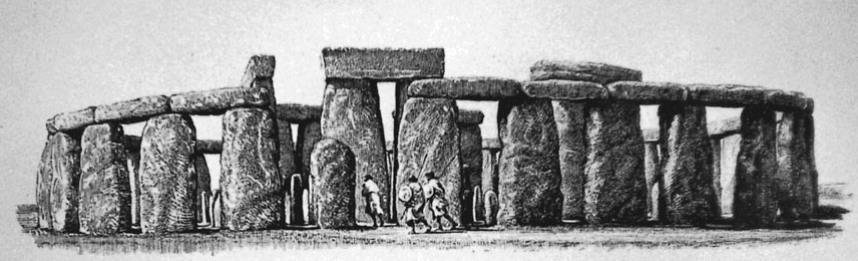

Fig. 2.3. Stonehenge. Neolithic and early Bronze Age tribes in Britain built and rebuilt the famous monument at Stonehenge as a regional ceremonial center and as an “observatory” to track the seasons of the year

Construction required an estimated 30 million man-hours, involving the excavation of 3,500 cubic yards of earth to create a circular ditch and bank. Builders erected the Heel Stone, weighing 35 tons, and transported 82 bluestones from Wales, 240 kilometers away. The outer circle consists of 30 uprights, each around 25 tons, capped by lintels. Inside stand the five monumental trilithons, with uprights averaging 30 tons; the largest likely exceeds 50 tons. The architects potentially used a standardized unit, the megalithic yard, and practical geometry to achieve the layout.

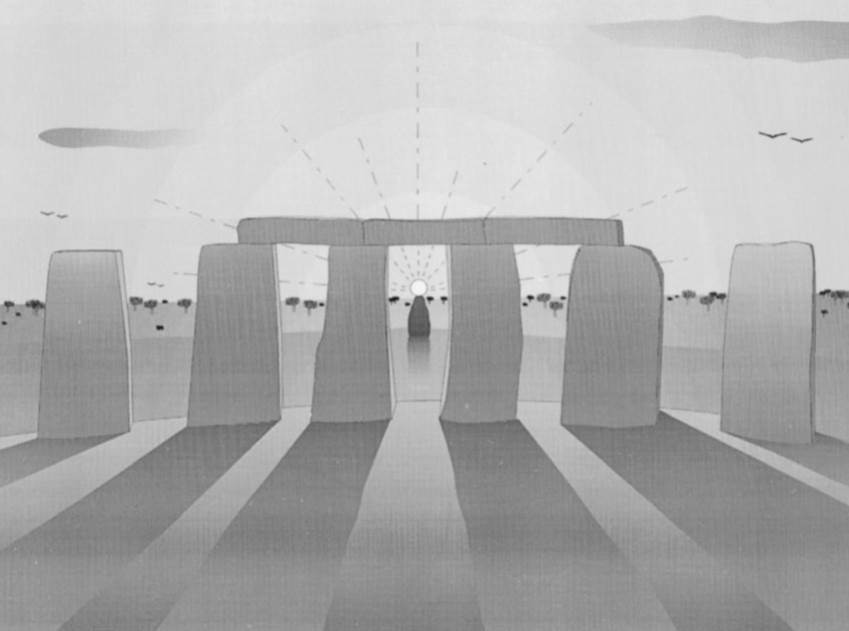

Fig. 2.4. Midsummer sunrise at Stonehenge. On the morning of the summer solstice (June 21) the sun rises along the main axis of Stonehenge and sits atop the Heel Stone

This labor, spanning generations, necessitated a stored food surplus and centralized authority for coordination. Neolithic farming communities on the plain achieved sufficient productivity levels to support such projects. While less intensive than later civilizations, this low-intensity agriculture generated the requisite surpluses for megalithic monument building, demonstrating their economic capacity.

Modern recognition of Stonehenge as an astronomical device resolved centuries of speculation. Early theories, like Geoffrey of Monmouth’s tale of Merlin, or attributions to Romans, Danes, or Druids, have been supplanted by scholarly consensus. It was a ceremonial center built by indigenous peoples, with astronomical functions for sun and moon worship and maintaining a regional calendar.

William Stukeley first documented its solar alignment in 1740. The monument aligns with the midsummer sunrise, where the sun rises over the Heel Stone. This primary orientation is annually verified and undisputed. Later 20th-century debates proposed it as a sophisticated observatory or computer; while contested, consensus affirms its role in tracking celestial motions.

The structure marks solstices and equinoxes for both sunrise and sunset, and tracks the complex lunar standstills. This required sustained observations over decades and mastery of horizon astronomy. The monument embodies this ritual astronomy, reflecting deep understanding of celestial regularities and systematic nature observation.

Although likely managed by religious elders or hereditary experts, it does not evidence a professional astronomer class. Stonehenge functioned as a celestial orrery or clock, accurately harmonizing the solar year with lunar cycles and serving as a precise seasonal calendar. This constitutes definitive Neolithic astronomy, preceding written records and full-time specialists.

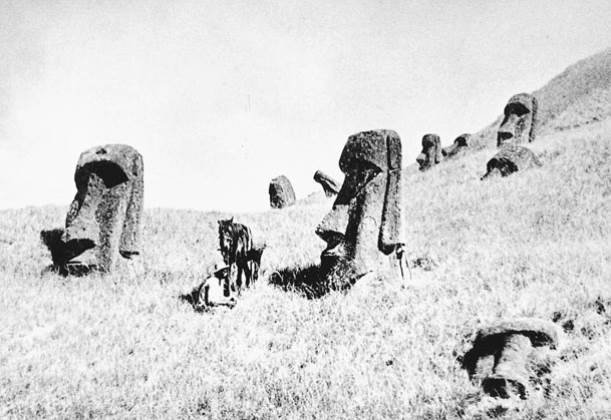

Parallel developments occurred globally, as seen on Easter Island (Rapa Nui). After settlement circa 300 CE, Polynesians prospered through sweet potato cultivation and fishing. They erected over 250 moai statues on astronomically oriented ceremonial platforms (ahu). The average moai stood 12 feet tall and weighed 14 tons, transported overland by large work gangs.

Fig. 2.5. Neolithic society on Easter Island. A society based on low-intensity agriculture flourished here for hundreds of years before it was extinguished by ecological ruin. During its heyday it produced megalithic sculptures called moai comparable in scale to Stonehenge and other monumental public works that are typical of Neolithic societies

The society eventually collapsed due to deforestation and ecological overshoot. The demand for firewood and canoe timber led to stripped resources, causing population crash from an estimated peak of 7,000-9,000 to a mere remnant. This highlights how Neolithic-level societies, even with astronomical knowledge, faced existential limits from demographic pressures and resource depletion.

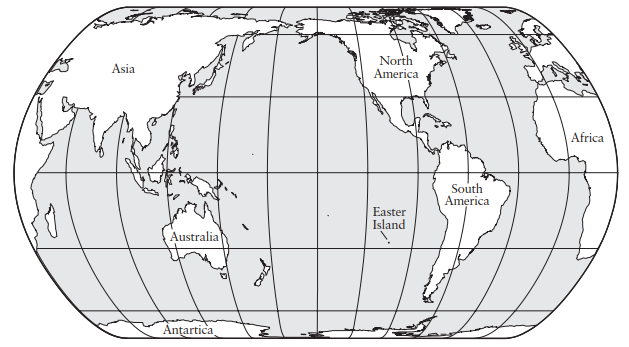

Map 2.2. Easter Island. This isolated speck of land in the South Pacific lies 1,400 miles off the coast of South America and 900 miles from the nearest inhabited island to the west. Polynesian seafarers, probably navigating by star charts and taking advantage of their knowledge of wind and current changes, arrived at Easter Island around ce 300. Europeans “discovered” the island in 1722.

Globally, Neolithic peoples used horizon markers to monitor solar and lunar motion, tracking seasons with vital information for farming communities. In resource-rich areas, surplus enabled elaborate constructions like Stonehenge. Ultimately, in regions like Egypt and Mesopotamia, these growing populations pressing against Neolithic resources catalyzed the great transformation to urban civilization.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;