The Neolithic Revolution: Origins, Technologies, and Global Impact of Early Farming Societies

A fundamental fact of human prehistory is that Neolithic communities, founded upon domesticated plants and animals, emerged independently across multiple global regions after 10,000 BCE. These separate hearths included the Near East, India, Africa, North Asia, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America. The profound physical separation between the Old World and the New World precludes explanations of simple cultural diffusion, a point further underscored by the distinct domestications of wheat, rice, corn, and potatoes. While appearing abrupt on a prehistoric scale, this transition was inherently gradual. Nonetheless, the Neolithic Revolution irreversibly transformed human societies and their environmental interactions, a world-altering impact that remains undisputed.

This revolution resulted from a cascading series of events. Research indicates that in many regions, human groups first established permanent villages while still practicing a Paleolithic economy of hunting and gathering, a phase known as complex foraging. These sedentary groups intensified plant collection and exploited a broad spectrum of secondary food sources like nuts and seafood. By inhabiting permanent houses, humans effectively domesticated themselves, a concept embedded etymologically in the Latin word domus, meaning "house." Ultimately, population pressures and the high nutritional yield of wild cereals catalyzed a full dependence on a food-producing way of life.

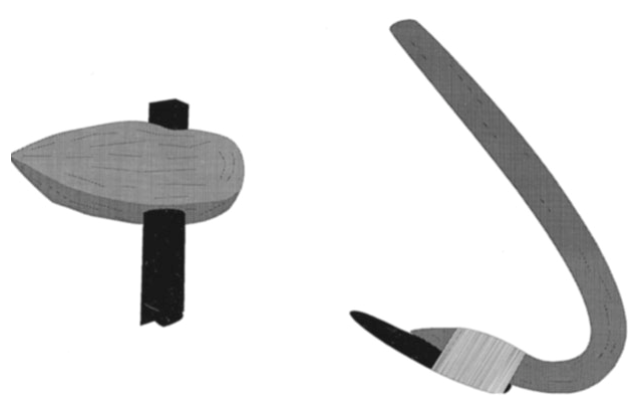

Fig. 2.1. Neolithic tools. Neolithic horticulture required larger tools for clearing and cultivating plots and for harvesting and processing grains.

Importantly, Paleolithic lifestyles persisted long after the first Neolithic settlements appeared roughly 12,000 years ago. As a cultural mode, it endures in a few surviving groups today. The Neolithic period itself encompasses an arc from simple horticulturists and pastoralists to complex late Neolithic "towns." Lasting approximately 7,000 years before the rise of civilization in Mesopotamia and Egypt, it was brief compared to the Paleolithic but spread geographically and defined lifeways for hundreds of generations, who experienced its seasonal, leisurely pace.

Two primary pathways led from foraging to food production: one from gathering to cereal horticulture and later plow agriculture; the other from hunting to herding and pastoral nomadism. Geography dictated this divergence: settled villages arose in regions with sufficient water, while arid grasslands fostered nomadic pastoralism. These distinct paths historically led to nomadic societies like the Mongols and Bedouins, and to the great agrarian civilizations, respectively.

Low-intensity farming, or gardening, defined early Neolithic economies, conducted on small cleared plots. This contrasts with later intensified agriculture employing irrigation and plows. Early farmers used stone axes and adzes for clearing and digging sticks or hoes for cultivation. In tropical zones, swidden agriculture or "slash and burn" became common. The Neolithic toolkit included polished implements like grinding stones and mortars and pestles, alongside smaller chipped tools. Antler picks were also vital. Processing grains required an elaborate suite of technologies for threshing, winnowing, storing, and grinding.

Plant domestication was a global, independent process involving genetic selection. In Southwest Asia, domesticates included wheats, barleys, rye, peas, lentils, and flax. Africa yielded millet and sorghum; North China, millet and soybeans; Southeast Asia, rice and beans. Mesoamerica contributed maize (corn), while South America offered potatoes, quinoa, beans, and manioc. Domestication altered plant genetics; for example, domesticated wheat retains its seeds for easier harvest, making it dependent on humans. This symbiotic relationship extended to commensal species like rats and house sparrows, which "self-domesticated."

Animal domestication developed from prolonged human contact with wild species, evolving from hunting to corralling, herding, taming, and breeding. The practices of the Sami (Lapp) people with reindeer illustrate this potential transition. The process involved selective slaughtering and breeding. Old World domesticates included cattle, goats, sheep, pigs, chickens, and horses. In the New World, Andean communities domesticated only llamas and guinea pigs, creating a comparative dietary deficiency in animal protein.

Animals provided multifarious benefits: converting inedible plants to meat, offering mobile food stores, and yielding secondary products. These included milk (processed into yogurts and cheeses), manure for fertilizer and fuel, hides for leather, and wool—first woven on Neolithic looms. Animals also supplied traction and transportation, cementing a new, managed dependence on other species.

After millennia, mixed economies combining horticulture and animal husbandry appeared. Late Neolithic groups used animals for traction and wheeled carts. This mixed farming was the historical route to intensified agriculture and civilization. The Neolithic Revolution thus represents a decisive historical turn initiated by humans in response to environmental changes.

Ancillary technologies flourished alongside farming. Textile production became a major innovation, involving shearing, processing flax or cotton, spinning thread, and weaving on looms. Similarly, pottery arose independently worldwide, primarily as a storage technology for agrarian surpluses. As a pyrotechnology, firing clay at over 900°C created artificial stone vessels; this knowledge later enabled metallurgy. Neolithic peoples also mastered wood and mud-brick construction, rope-making, and even early cold metalworking of raw copper, as evidenced by the tools of the "Iceman" from 3300 BCE.

The Neolithic was a profound social revolution. Decentralized villages of several hundred people replaced smaller Paleolithic bands, with the household as the central production unit. Settled life reshaped concepts of privacy and public space. Diets higher in carbohydrates and a sedentary lifestyle likely increased fertility. While a sexual division of labor persisted, horticulture's de-emphasis on hunting may have fostered greater gender equality. Evidence points to shamanistic practices and, in Europe, potential cults of Neolithic goddesses. Early societies were patriarchal but less rigidly stratified than later civilizations.

Initially, little occupational specialization existed. However, later Neolithic food surpluses and exchange fostered complex settlements with full-time potters, weavers, masons, and emerging leaders. Social stratification grew, leading to tribal chiefdoms or "big men" societies based on kinship and the redistributive control of goods.

Compared to affluent Paleolithic foraging, early Neolithic life may have involved more labor and a less varied diet. Its definitive advantage was a greater caloric yield, supporting vastly higher population densities—estimated at a hundredfold increase per square mile. This demographic shift allowed Neolithic economies to expand rapidly.

By 3000 BCE, thousands of villages networked the Near East. Wealthier centers like Jericho emerged as true towns; by 7350 BCE, it was a walled settlement of over 2,000 people. These fortifications were necessitated by the new phenomenon of surplus wealth worth raiding. While Paleolithic conflict existed, the Neolithic institutionalized warfare for resource theft and protection. Hunter-gatherers were ultimately marginalized or absorbed, leaving only idealized echoes in "Garden of Eden" myths.

This new economic mode granted humans greater control over nature, with significant ecological consequences. The domestic systematically replaced the wild, rendering the revolution irreversible. Transformed habitats and unsustainable population densities made a return to the Paleolithic impossible, setting humanity irrevocably on the path toward complex civilization.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 2;