Scale. Place. Regions

Geographical analysis is conducted at many different scales. The scale of geographical analysis can be global, encompassing the entire world: local, incorporating only a single building, park, or other property; or anywhere between these extremes.

In global analyses, the geographer generalizes considerably, ignoring local-scale details. The geographer investigating the distribution of earthquakes and earthquake damage throughout the world pays little attention to the impacts of a particular earthquake in a particular neighborhood.

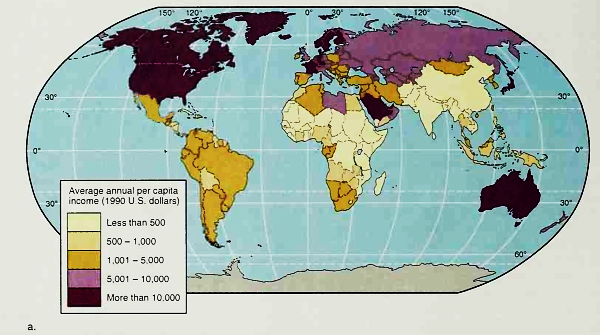

Likewise, geographers investigating international differences in per capita income recognize that the United States is wealthier than Brazil. Mexico, or Venezuela. At a local scale, however, clear differences in income are evident within even small areas within any country (Figure 1-8).

Figure 1-8. The Distribution of Wealth. Maps of the distribution of wealth per capita illustrate the impacts of scale on geographical research. Some maps focus on international distributions (a); others concentrate on regional or local differences in phenomena (b)

Events at a global scale influence those at local or regional scales, and vice versa. We have already seen that natural disasters, such as the earthquake in San Francisco, can affect social and economic conditions in other places considerably. Similarly, drought in Russia may result in expansion of the farm economy in the American Great Plains.

War in Southwest Asia can affect the price you pay for gasoline at the local service station. Worldwide economic recession can result in the closing of manufacturing plants, increasing local rates of unemployment, cutting retail sales, and encouraging migration away from the community.

Place. Ultimately, basic geographical questions such as those presented earlier in this chapter are questions about place. Where on the surface of the Earth is a particular place located? Where is it located with respect to other places? What factors are responsible for the development of particular places? How do places interact with one another? How are phenomena distributed within places? These questions call attention to the fact that geographers are concerned not only about distributions of phenomena but about places themselves.

In general, we regard "places" as small-scale entities, but the concept of place is not dependent on scale. For example, we can regard Bunker Hill as a place, but we can also conceptualize the city of Boston, the Commonwealth (State) of Massachusetts, New England, the United States, and North America as places. The uniqueness of Bunker Hill as a place is enhanced by its location within these larger places.

Geographers are interested in the unique qualities and meanings of places. In examining a place, a geographer pays attention to three critical aspects that define it. These include the physical environment, the built environment and social characteristics and relationships.

The Physical Environment. Aspects of the physical environment that affect places include its climate, vegetation, topography, terrain, wildlife, water supply, natural-resource base, and so on. The physical environment affects individual places in numerous ways. In response to the earthquake hazard, the state of California has enacted stringent building codes requiring new homes to be constructed in such a way as to withstand major earthquake damage. Specific physical conditions are essential to many resort areas that feature outdoor recreation. Dry or warm conditions can spell economic disaster for operators of ski resorts in the Swiss Alps or the Colorado Rockies. Periods of cool, cloudy weather can ruin trips to beach resorts.

The Built Environment. Many types of animals are capable of modifying their local physical surroundings. Beavers are well known for their ability to create lakes and wetlands by damming small streams. But human beings alone are capable of large-scale environmental modification. Human intervention can minimize the direct influence of the physical environment on places. Domed sports stadiums permit professional baseball and football to be played in the heat of Houston, the cold of Minneapolis, and the rain of Seattle.

Enclosed shopping malls provide a wealth of opportunities for various activities throughout the year, regardless of weather. Every morning, malls across the United States host large numbers of "mall walkers" where not only can they walk comfortably in the climate-controlled environment of the mall, but they are welcomed by merchants as potential customers.

Social Relationships. Human activity is a third essential defining characteristic of any place. The same location can become an entirely different place as human activities and social relationships change. The impact of social changes on location can be identified at both long and short time scales. For example, the San Francisco we know today is vastly different from how it was at the time of the 1906 earthquake, or during its period of Spanish rule in the early nineteenth century, or prior to the arrival of Anglo-Americans five centuries ago. In examining social relationships in any place, the geographer pays careful attention to the underlying economic, social, and political history- and development of that place and its relationships with other places.

The influence of time on place can also be observed in the short run. At various times, the same location may be frequented by entirely different populations (Figure 1-9). At noon on a business day, for example, the downtown area of a large metropolis bustles with activity.

Figure 1-9. Same Place, Different Time. The idea that a place's qualities are influenced by social relationships is illustrated by these photographs, showing the same location, Quincy Market in Boston, at different times of the day. During the business day, the pace is hurried as employees rush to complete transactions and maintain their busy schedules. On a weekend evening business gives way to relaxation and recreation

Executives and white-collar workers grab hurried lunches before rushing back to their offices. Streets are jammed with harried motorists fighting traffic snarls. In the evening, the same streets may be packed with tourists, visitors, and residents of the metropolitan area enjoying restaurants, theaters, and night life. The hurried pace of midday gives way to a more relaxed, recreation-oriented atmosphere. At four o'clock in the morning, the streets are largely deserted. Only the activities of garbage collectors, delivery personnel, and other employees preparing the city for another day of frenetic activity disturb the quiet.

Regions. In ordinary conversation, we often use the word region to describe a large place. New England, Western Europe, Southeast Asia, and southern California are places that we commonly refer to as regions. A region can also be defined as a collection of places with similar attributes. Any region has a unique set of characteristics that distinguishes it from other regions.

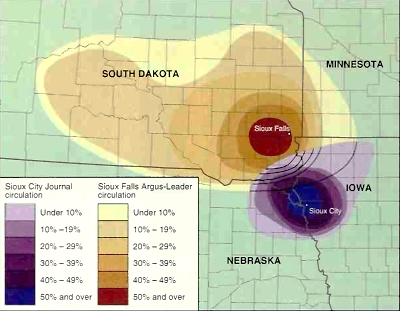

In analyzing regions, geographers frequently employ the concepts of formal regions and functional regions (Figure 1-10). A formal region is one in which the distinguishing attributes are present throughout the region.

Figure 1-10. Formal and Functional Regions. A formal region is defined by a boundary that separates places within it from those outside it. A functional region, on the other hand, has no definite boundary. A newspaper-circulation area is a typical functional region

All places within the region share one or more qualities that are absent elsewhere. A city, county, state, or other unit of government with defined boundaries is an example of a formal region. Every location within a formal region shares that region's essential defining characteristic.

By contrast, a functional region is one in which the defining characteristics are found at different densities or intensity levels within the region. The circulation areas of newspapers and viewing areas of television stations are typical functional regions.

Date added: 2023-01-05; views: 636;