History and Origins. The spread of wheat farming

Origins. Scientists believe that wild relatives of wheat first grew in the Middle East. Species from that region-wild einkorn, wild emmer, and some wild grasses—are the ancestors of all cultivated wheat species. At first, people probably simply gathered and chewed the kernels. In time, they learned to toast the grains over a fire and to grind and boil them to make a porridge. Frying such porridge resulted in flat bread, similar to pancakes. People may have discovered how to make yeast bread after some porridge became contaminated by yeast.

Wheat was one of the first plants to be cultivated. Scientists think that farmers first grew wheat about 11 ,000 years ago in the Middle East. Archaeologists have found the remains of wheat grains dating from about 9,000 B.C. at the Jarmo village site near Damascus, Syria. They also have found bone hoes, flint sickles, and stone grinding tools that may have been used to plant, harvest, and grind grains.

The cultivation of wheat and other crops led to enormous changes in people's lives. People no longer had to wander continuously in search of food. Farming provided a handier and more reliable supply of food and enabled people to establish permanent settlements. As grain output expanded, many people were freed from food production and could develop other skills. With the improvement of agricultural and processing methods, people in some areas grew enough grain to feed people in other lands. In this way, trade developed. Thriving cities replaced tiny villages. These changes helped make possible the development of the great ancient civilizations.

The spread of wheat farming. By about 4,000 B.C., wheat farming had spread to much of Asia, Europe, and northern Africa. New species of wheat gradually developed as a result of the accidental breeding of cultivated wheats with wild grasses. Some of the new wheats had qualities that farmers preferred, and so those kinds began to replace older wheats. Emmer and einkorn were cultivated widely until durum wheat appeared about 500 B.C. By about A.D. 500, common wheat and club wheat had developed.

Wheat was brought to the Americas by explorers and settlers from many European countries. In 1493, Christopher Columbus introduced wheat to the New World on his second trip to the West Indies. Wheat from Spain reached Mexico in 1519 and Argentina by 1527. Spanish missionaries later carried wheat with them to the American Southwest. In Canada, French settlers began growing wheat in Nova Scotia in 1605.

English colonists planted wheat at Jamestown, Va., in 1611 and at Plymouth Colony in New England in 1621. But the New England colonists had less luck with wheat than with the corn the Indians gave them. Colonists from the Netherlands and Sweden had more success growing wheat in New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Pennsylvania.

Wheat farming moved westward with the pioneers. Wheat grew well on the Midwestern prairies, where the climate was too harsh for many other crops. Large shipments of wheat traveled to markets in the East by canal and railroad. By the 1860's, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, and Ohio had become leading wheat-producing states.

The introduction of winter wheat gave the U.S. wheat industry a major boost. In the 1870s, members of a religious group called the Mennonites immigrated from Russia to Kansas. They brought with them a variety of winter wheat called Turkey Red, which was extremely well suited to the low rainfall on the Great Plains. Turkey Red and varieties that were developed from it soon were planted on nearly all the wheat farms in Kansas and nearby states. Many present-day varieties of wheat grown in the United States can be traced to Turkey Red.

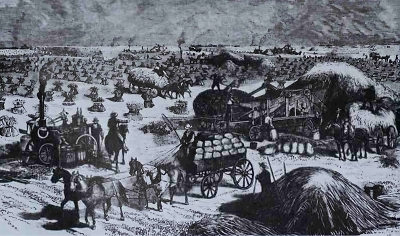

A steam-powered threshing machine, above, was used by wheat farmers of the late 1800's and early 1900s. The machine separated the kernels from the stalks and blew the husks from the kernels. Threshers were so expensive that a group of farmers bought and shared one machine

The mechanization of wheat farming. From the beginnings of agriculture until the early 1800's, there was little change in the tools used for wheat farming. For thousands of years, farmers harvested wheat by hand with a sickle or a scythe. The stalks were then tied into bundles and gathered into piles to await threshing. To thresh the grain, livestock trampled the stalks or farmers beat the stalks with a hinged stick called a flail.

After the grain was loosened from the stalks, the wheat was tossed into the air. The chaff blew away, leaving the kernels behind. This process was called winnowing. Much grain spoiled because it took so long to harvest and thresh it.

Machines that were developed in the 1800's made wheat farming far more efficient. The American inventor Cyrus McCormick patented the first successful reaping machine in 1834. By the 1890s, most reapers had an attachment that tied the stalks in bundles. Also in 1834, two brothers from Maine, Hiram and John Pitts, built a threshing machine. The thresher could do in a few hours the work that once took several days. A combined harvester-thresher, or combine, was developed in the 1920's by Hiram Moore and John Haskall of Michigan. However, most farmers continued to use separate reapers and threshers. During the 1920's, a shortage of farm labor coupled with improvements in combines led more farmers to use them.

Until the late 1800's, most farm equipment was powered by farm animals or human labor. During the 1880's, steam engines gradually replaced the animals that pulled most farm machinery in the United States. By the early 1920's, internal-combustion engines were used to power tractors and other farm machines.

Mechanization has greatly reduced the amount of human labor needed to grow wheat. Before 1830, it took a farmer more than 64 hours to prepare the soil, plant the seed, and cut and thresh 1 acre (0.4 hectare) of wheat. Today, it takes less than 3 hours of labor. Mechanization has also enabled farmers to cultivate much larger areas. Using hand tools, a farm family can grow about 2.5 acres (1 hectare) of wheat But with modern machinery, the same family can farm about 1,000 acres (405 hectares).

Breeding new varieties of wheat. Some of the most important advances in the history of wheat resulted from the scientific breeding of wheat begun during the 1900's. By developing new varieties of wheat, plant breeders greatly increased the yield of wheat per acre or hectare of land. Some varieties have higher yields because they can resist diseases or pests. Others mature early, enabling the grain to escape such dangers as early frosts and late droughts. Breeders also developed plants with strong stalks that can support a heavy load of grain. Many high-yield varieties require large amounts of fertilizers or pesticides.

During the mid-1900's, agricultural scientists led a worldwide effort to boost grain production in developing countries. This effort was so successful that it has been called the Green Revolution. Its success depended primarily on the use of high-yield grains. In 1970, American agricultural scientist Norman E. Borlaug was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for wheat research that led to the development of these varieties.

The Green Revolution reduced the danger of famine in many developing countries. It helped these countries become less dependent upon imported wheat for their growing population. It also helped focus attention on obstacles to increasing the world's food supply. For example, water supplies are often limited and soils are of poor quality.

Many farmers cannot afford irrigation systems or the large amounts of fertilizers and pesticides the new grains require. In some developing countries, grain can be damaged or spoiled by insects, rodents, poor transportation, and poor distribution systems. Finally, in many countries, the population is growing faster than the food supply, offsetting the gains achieved by the Green Revolution.

Date added: 2023-01-25; views: 902;