The Movement of the Continents. The History of a Theory

As world maps became complete and more accurate, observant individuals were intrigued by the shapes of the continents on either side of the Atlantic Ocean. The possible “fit” of the bulge of South America into the bight of Africa was noted by the English scholar and philosopher Francis Bacon (1561-1626), the French naturalist George Buffon (1707-88), the German scientist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), and others.

In the 1850s the idea was expressed that the Atlantic Ocean had been created by a separation of two landmasses during some unexplained cataclysmic event early in the history of the Earth. Thirty years later it was suggested that a portion of the Earth’s continental crust had been torn away to form the Moon, creating the Pacific Ocean and triggering the opening of the Atlantic. As scientific studies of the Earth’s crust continued, patterns of rock formation, fossil distribution, and mountain range placement began to show even greater similarities between the lands now separated by the Atlantic Ocean.

In a series of volumes published between 1885 and 1909, an Austrian geologist, Edward Suess, proposed that the southern continents had been joined into a single continent he called Gondwanaland. He assumed that isostatic changes had allowed portions of the continents to sink and create the oceans between the continents.

This idea was known as the subsidence theory of separation. At the beginning of this century, Alfred L. Wegener and Frank B. Taylor independently proposed that the continents were slowly drifting about the Earth’s surface. Taylor soon lost interest, but Wegener, a German meteorologist, astronomer, and Arctic explorer, continued to pursue this concept until his death in 1930.

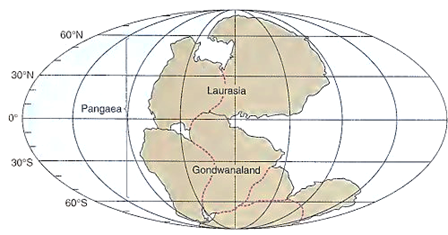

Wegener’s theory, often called continental drift, proposed the existence of a single supercontinent he called Pangaea (fig. 2.6). He thought that forces arising from the rotation of the Earth combined with tidal forces began Pangaea’s breakup. First, the northern portion composed of North America and Eurasia, which he called Laurasia, separated from the southern portion formed from Africa, South America, India, Australia, and Antarctica, for which he retained the earlier name Gondwanaland. Laurasia and Gondwanaland are shown in figure 2.6.

Fig. 2.6. Pangaea 200 million years before the present. Wegener’s supercontinent is composed of the two subcontinents, Laurasia and Gondwanaland

The continents as we know them today then gradually separated and moved to their present positions. Wegener based his ideas on the geographic fit of the continents and the way in which some of their older mountain ranges and rock formations appeared to be related to each other when the landmasses were assembled to form Pangaea.

He also noted that fossils more than 150 million years old collected on different continents were remarkably similar, implying the ability of land organisms to move freely from one landmass to another. Fossils more recent than 150 million years old showed quite different forms in different places, suggesting that the continents and their evolving populations had separated from one another.

Wegener’s theory provoked considerable debate in the 1920s, but most geologists agreed that it was not possible to move the continental rock masses through the rigid basaltic crust of the ocean basins. There was no mechanism to cause the drift, and the theory was not regarded very seriously in the scientific community; it became a footnote in geology textbooks.

Date added: 2023-11-08; views: 752;