Measurements and Accounting in ancient times

A Greek city would have an official who oversaw the weights and measures of the marketplace (agora). At the Tholos, the officials who were in charge of the markets, mints, and other offices used their official weights to ensure that merchants were honestly conducting business. Examples of these weights have been found in and around the agora in bronze or clay. Official dry measures were also kept in the form of a mug or cylinder, while liquid measures were in the form of jugs or amphora.

The agoranomoi (market officials) were charged with ensuring that weights and measurements were maintained accurately. The Greeks would also ensure that they could accurately measure, weigh, and record their acts so that they could carry out surveys, build structures, engage in trade, and keep accounts of their business.

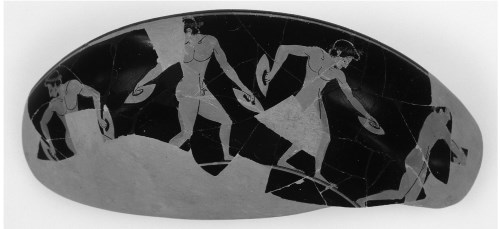

Four jumpers carrying jumping weights in both hands. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Villa Collection, Malibu, California)

The Greeks based their units of measurements on a system of increasing units tied to a simple unit of measurement. Length was based on the finger (daktylos), the size of the thumb or about three-fourths of an inch, and the foot (pous). These units were never standardized throughout the Greek world. For example, the pous in Aegina was longer than that in Athens by about an inch and half (13.1 inches versus 11.7 inches). Although the exact lengths varied, each state would follow the same proportions and multiples. Two daktyloi equaled one kondylos, while four equaled one palm (doron). Two doron (equaling eight daktyloi) measured a halffoot. A spithame, or twelve daktyloi, produced a span of all the fingers, presumably spread out. Sixteen daktyloi would then equate a pous, while eighteen daktyloi (pygme) would measure a forearm. Finally, a cubit (pechys) had twenty-four daktyloi, equivalent to just over eighteen inches. These were the smaller units, used to measure small objects.

The next sizes above these small units began with the foot or pous (plural podes). Above the foot was the haploun bema, or step, equivalent to two-and-a- half podes. This would have been the stride, while a bema, or five podes, produced a pace. Just above this was an orgyia, or fathom of six podes, often used for measuring the depth of water, which was useful in determining if a ship could pass through a particular waterway. The dekapous as the name implies, meant 100 feet, while 100 feet produced aplethron, which was usually the width of a Greek racecourse, and 6 plethora made a stadion or stade, producing a length of approximately 172 yards. Herodotus indicated that a stadion equaled 600 feet, equivalent to an eighth of a Roman mile. A diaulos was a double stadion race of 1,200 feet, equivalent to the modern 400 meters. Eight stadia was equivalent to the Roman mile, while twelve stadia was a dolichus, or long race at 7,200 feet.

This may have been the most common extensive distance since the Greeks would adopt from the Persians the league orparasanges, a length of thirty stadia mentioned by Herodotus, equaling nearly three-and-a-half miles. It probably came from an earlier Middle Eastern term, perhaps frasang or fasukh referring to what an army could march during a predetermined period (probably an hour). Herodotus also stated that a parasanges was equivalent to half an Egyptian schoenus, meaning that it measured 60 stadia, although later it may have measured only 40. It appears that the schoenus varied according to the region and time. Xenophon, writing about 400, indicated that a stage was equivalent to 160 stadia, or about eighteen-and-a- half miles.

The terms for the amount of materials and land were based on the compounding of smaller units. These measurements increased in multiples of the smallest unit, the daktylos, giving way to the pous and then to the stadion. These measurements were then used for determining area. A pous also meant a square foot, while a hexapodes, or thirty-six podes, meant a 6-square-foot area. An akaina meant 100 square feet, while an hemiektos equated to a half of a sixth of a hektos (a twelfth of a plethron), while a hektos measured a sixth of a plethron, at 1,666 2/3 podes. An aroura, a common unit of measurement in Egypt for farmland, equaled 2,500 podes, or 2,500 square feet, about two-thirds of an acre. Finally, a plethron measured 1,0000 podes.

Volume also was determined by a series of smaller units that constantly built upon the previous units. For liquid measurements, the kochliarion was described as a spoon, or about .15 ounce, while a mystron was two-and-a-half kochliaria. Ten kochliaria equaled one kyathos or Roman cyathus, or just above one-and-a- half ounces. An oxybathon, or Roman acetabulum, was one-and-a-half kyathoi. Double this amount was a tetarton, or Roman quartarius, at three kyathoi. A kotyle had six kyathoi just above nine ounces, while doubling this would give a xestes, or Roman sextarius, equaling slightly more than a pint, a common measurement. A chous was six times the amount of a xestes, with seventy-two kyathoi; eight choes was a keramion, about seven gallons, while a metretes (at twelve choes) was a Roman amphora. Dry measures were also based on the similar wet measures, with the kochliarion, kyathos, oxybathon, kotyle, and xestes, equivalent to the wet measures. Above the xestes was the choinix, with twenty-four kyathoi, and the medimnos, at forty-eight choinikes. These latter measures were commonly used for grain. This unit could then be divided into a third or tritaios, a sixth or hekteus, and a twelfth or hemiektos, as well as other smaller units.

The Greeks used currency definitions for weights. There were two major standards, the Euboea (Attic) and the Aegina. The smallest unit was the obol, with six obols equaling a drachma, while 100 drachmas was a mina and a talent had 60 minae, or 6,000 drachmas. An Attic talent was equivalent to fifty-seven pounds, while the Aegina standard was eighty-three pounds. Supposedly, the Attic obol had twelve barley grains, but like other measurements, the weights varied greatly.

The Greeks used a system of bookkeeping that was not as sophisticated as modern accounting methods. Modern accounting methods use what is called a double-entry system, where on the left side are liabilities or debits and on the right side are assets or credits. In addition, that system creates several accounts in which each transaction is recorded twice in ledgers for assets, liabilities, equities, expenses, or revenues, and all the debit and credit transactions balance. A business would need several pages or books to produce a complete accounting picture.

Most businesses use a system of debits and credits in an income statement to convey the health of a project, company, government, or other entity. A simplified system, or single-entry system, records transactions only once, and debits and credits do not necessarily balance. This would be akin to a check ledger, where income is recorded as assets or deposits and then checks written as liabilities or debits. The ancient Greeks used this type of system, but even then, it was often incomplete.

The Greeks did not use double columns to record their transactions, and in fact did not even use single columns for computations; rather, it would be used more for aesthetic value or to keep track or find individual items for easy reference. The Greeks used words that are often translated as debit or credit but really meant receipts and expenditures, again producing a system like a checking ledger. During the Classical period, most of the accounts that survive are on inscriptions and usually relate to public expenditures. The later sources from Egypt do not show the practice that receipts were placed on one side and payments on the other side. It was during the Classical Age, after 600, that money came into use.

In the distant past, barter was used and goods were equated to an ox, so that in the Iliad, the victor of a competition won a tripod worth twelve oxen (the loser won a woman worth four oxen). In the Classical Age in Athens, building accounts for the temple of Athena on the Acropolis show a forward balance with revenues added, followed by expenses such as wages and supplies, and ending with a balance for the period. Other accounts show the same structure—revenue followed by expenses and ending with a balance. The inscriptions do not show a tabulation of material but give minute details of expenses.

The accounts were meant to show how the various treasuries were used and account for all of the expenses scrupulously so the gods would not be offended. The citizenry then knew how much was spent, so that full transparency occurred. Interestingly, the accounts mention simple items such as sandals in great detail, so that the concept of petty cash for items not mentioned up to a certain amount is unknown. The Greeks presented their accounts in a continuous narrative, with receipts and expenditures mentioned together continuously.

The Athenians in the latter part of the fifth century, during the height of their empire, deposited surpluses of their tribute into the account for the temple of Athena, from which they borrowed during times of crises at low rates of interest or even no interest at all. These transfers of monies from the temple to the city accounts were simple bookkeeping transactions. Pericles seems to have developed this project so as to ensure that surplus tribute would be in the hands of the gods to ensure that it would not be used indiscriminately, at the whim of the Assembly. To simply transfer the money would be impious unless the gods approved it. The Greeks probably kept a record of debts either owed to Pericles or which Pericles owed.

These systems of weights, measurements, and accounting allowed the Greeks to fully develop and record the actions of their society. The Greeks had an official called the agoranomoi, who ensured the honesty of the markets and merchants.

Date added: 2024-09-09; views: 436;