Nitrogen Uptake

Nitrogen is present in the soil in many different chemical forms. The three most abundant ones are nitrate (NO3-), ammonium (NH4+) and amino acids. Their relative contributions can vary widely depending on environmental conditions and competition by soil microorganisms. Ammonium is the main N source under anoxic reducing conditions (e.g. in wetlands) or at low pH, when nitrification by microorganisms is impaired. Rice plants in paddy fields, for instance, utilise mostly ammonium. Nitrate dominates at higher pH values and in more oxidising aerobic soils. Amino acids are released by the breakdown of proteins in soil organic matter.

When mineralisation is slow—for instance, because of low temperatures in high-altitude habitats or boreal forests—organic N in the form of amino acids can represent a substantial nitrogen source. Microbial competition is further dependent on mobility of the different N forms in the soil. Nitrate is more mobile in the soil solution because of its negative charge and is therefore less prone to utilisation by microorganisms before it reaches the surface of a plant root (Miller and Cramer 2005).

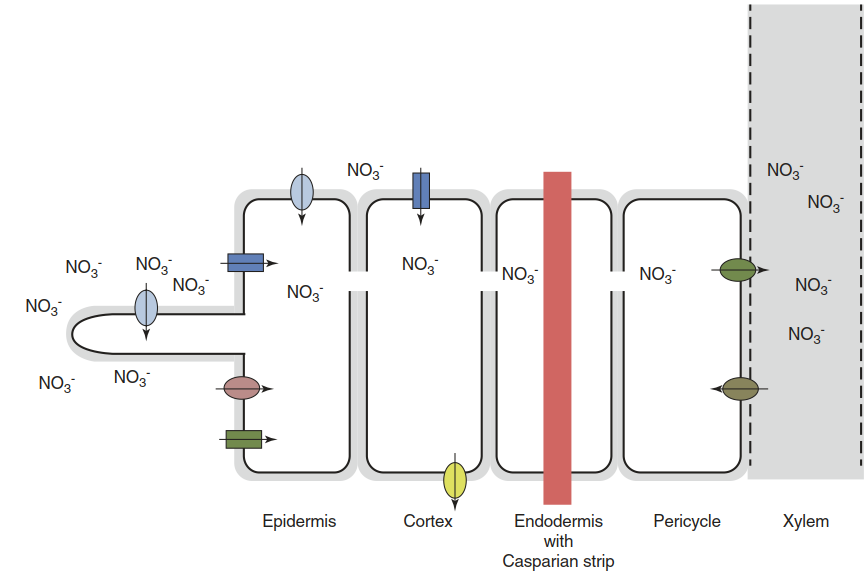

Plants possess multiple uptake transporters to be able to optimally exploit the hugely varying N sources. Transporters differ in substrates, substrate affinities, localisation of expression and regulation. In this way they provide a set of tools to fine-tune uptake activity in response to external supply. Nitrate concentrations in the soil solution can vary between micromolar and millimolar. Low-affinity transporters for nitrate uptake at high external supply belong to the NRT1 protein family. Their KM values are in the millimolar range. NRT2 family members are high-affinity transporters with a KM value for nitrate of around 50 μM. They are structurally not related to NRT1 transporters and mediate nitrate/H+ antiport (Fig. 7.13).

Fig. 7.13. Nutrient acquisition by the plant root is dependent on families of transporters differing in affinity, expression level and localisation. The example of nitrate is shown. Both uptake and efflux activities are involved in supplying nitrate in the right concentrations to roots and—via the xylem—shoots. Ovals represent members of the low-affinity NRT1 transporter family; rectangles represent members of the high-affinity NRT2 transporter family. The storage of nitrate in root cell vacuoles is not shown

Transporters accounting for low-affinity ammonium uptake have not been identified yet. High-affinity uptake is dependent on AMT1 proteins. They function as uniporters (see overview scheme in Fig. 7.9). Typically for nutrient uptake transporters, different isoforms (six in A. thaliana) are expressed in root hairs, the root cortex and endodermis cells.

The molecular understanding of amino acid uptake is much more limited than that of nitrate and ammonium uptake. Transporters with varying substrate spectra exist. Little is known about their contribution to N acquisition (Svennerstam et al. 2011, Chap. 11, Sect. 11.2.2.1).

Nitrogen is one of two nutrients (besides sulphur) that have to be assimilated into organic compounds. While ammonium can be directly assimilated, nitrate has to be reduced first to nitrite and then to ammonium. Nitrate assimilation can, depending on the plant species, occur preferentially in root cells or in leaf cells. The first product of nitrogen assimilation is glutamate. All other N-containing molecules are synthesised from this amino acid (for more details, see plant physiology and plant biochemistry textbooks).

Date added: 2025-01-27; views: 303;