White-rumped Vulture (Gyps bengalensis Gmelin 1788)

Physical appearance. The White-rumped vulture (Gyps bengalensis), a typical griffon, is the smallest of the griffons, but is still a very large bird. As a medium-sized vulture it weighs between 3.5 and 7.5 kg (7.7-16.5 lbs), is between 75 and 93 cm (30-37 in) in length, and has a wingspan of 1.80-2.6 m (6.3-8.5 ft) (Alstrom 1997; Ferguson-Lees et al. 2001; Rasmussen and Anderton 2005).

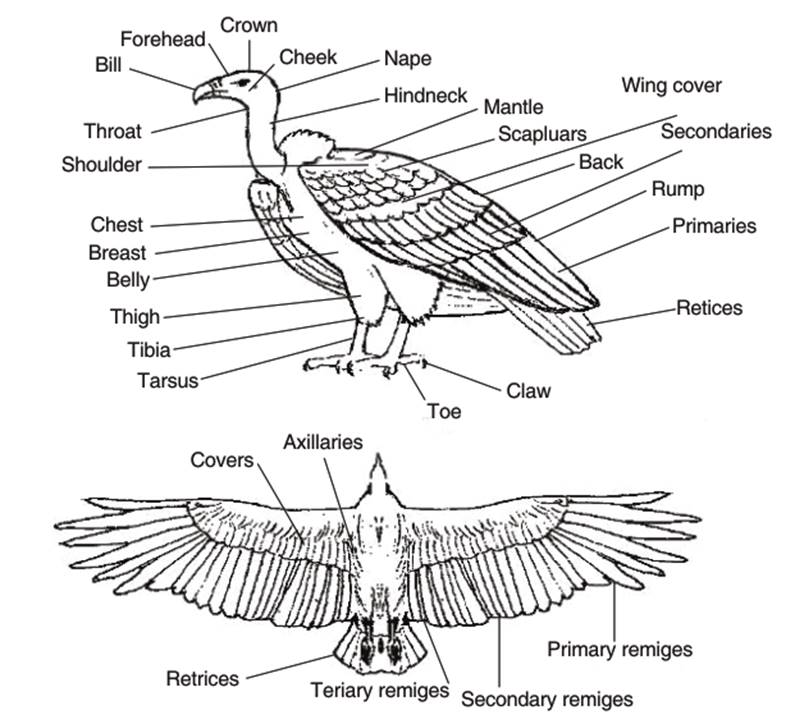

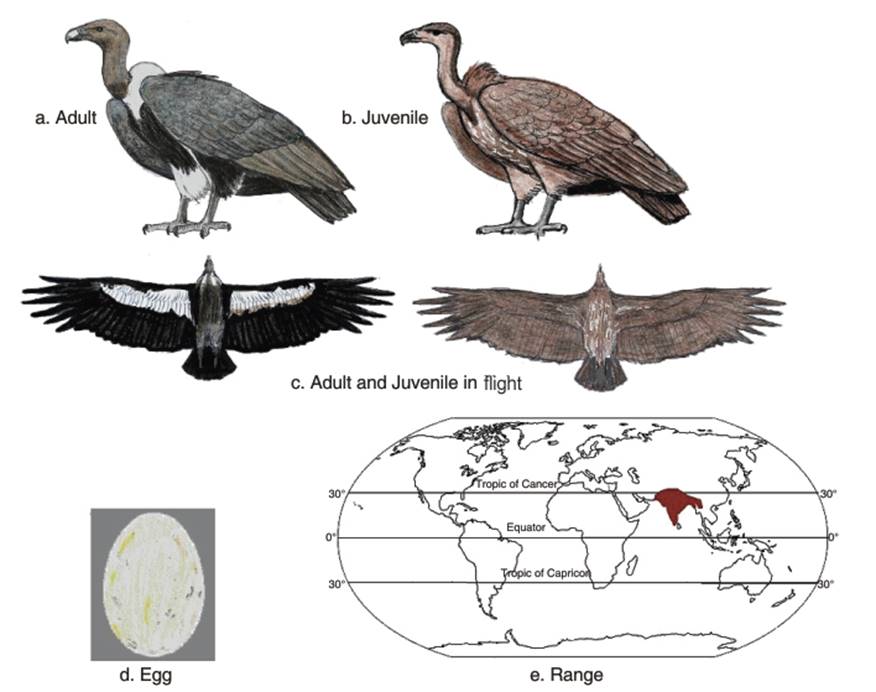

The dominant plumage is blackish, with slate-grey to silvery secondaries (Fig. 1.1a; see also Fig. 1 for an illustration of the locations of the various feathers). The underside is marked with whitish streaks and the back, rump and underwing coverts are whitish. The neck is unfeathered, partly down covered, slightly pink or maroon tinted, with a white neck ruff slightly open at the front, the bill is large with slit nostrils. The wings have dark edges and white linings, and black undertail coverts are visible on an adult bird in flight (Rasmussen and Anderton 2005). The coloration of this species therefore differs strongly from the White-backed vulture of Africa.

Fig. 1. Feathers on a Vulture

The juveniles acquire adult plumage at the age of four to five years (Fig. 1.1b). The juvenile is described as dark brown, with thin whitish streaks. Some feathers, especially the mantle and scapulars, lesser and median coverts are dark brown, while the greater coverts are blackish brown. The lower back and rump area are brown rather than white as in the adult (Rasmussen and Anderton 2005). The bare skin of the head is colored greyish-white, and the neck may also be tinged pinkish or bluish, with a dark grey throat. Both the head and neck are covered with scattered pale brown, grey and/or off white feathers. The cere and the bill are blackish, and the top of the upper mandible is pale bluish in the subadult. The legs, feet and iris of the juvenile are the same as those of the adult. The subadult is intermediate between the juvenile and the adult (Alstrom 1997).

In flight from below, white wing-linings on the wings, and black undertail coverts, are visible on an adult bird (Rasmussen and Anderton 2005). There are white underwing-coverts, with dark leading edges, contrasting with the blackish body (Fig. 1.1c).

Fig. 1.1. White-rumped Vulture

Classification.The White-rumped vulture was once classified as closely related to the African White-backed vulture. G. bengalensis and G. africanus have been classified by some as a separate genus, Pseudogyps. As mentioned above, this was based on physical attributes; the smaller body size compared to other species, and the smaller number of rectrices or tail feathers (12 vs. 14) compared to other Gyps vultures (Mundy et al. 1992; Sharpe 1873, 1874; Peters 1931). Although not all scientists agree with this classification, Lerner et al. (2006: 169) found a very close genetic match between the two white-backed vultures. For example, Seibold and Helbig (1995) argue that molecular data do not support the split from Gyps to a separate genus. As can be seen in the diagrams, its coloration differs strongly from the white- backed vulture of Africa (Fig. 1.1d). Wink (1995: 877) noted 'we suggest that the name Pseudogyps should be omitted and the respective taxa included in the Genus Gyps. G. africanus clearly differs from G. bengalensis, indicating that both vultures represent distinct species' (see also Dowsett and Dowsett-Lemaire 1980).

Foraging. The White-rumped vulture, in common with other vultures, begins foraging in the morning, when the thermals are strong enough to allow extensive soaring flight. Due to their comparatively smaller size, they are dominated by the larger Asian vultures, such as the Red-headed vulture. The main foraging and nesting areas are open plains and sometimes hilly areas, with grass, shrubs and light forest. A highly social vulture, it nests and roosts in large numbers, usually on trees near human habitation (Cunningham 1903; Morris 1934; Ali et al. 1978).

Breeding. For the nesting and egg-laying period, a study by Baral and Gautam (2007) found that the egg-laying period occurred from late September to late October, the incubation period from December to January and the nesting period from February to May. This was supported by a study by Sharma (1969: 205) in Jodhpur, India which noted that 'fuller nesting behavior gets under way only during December, when minimum temperatures drop to about 11°C and relative humidity to about 50%.' These nesting activities peak in January when the minimum temperatures are reached (about 8°C), the relative humidity is around 50% and the days are the shortest (10.24 hours). In February into March, the temperatures rise to 14°C and above, and the relative humidity is around 60%. The researchers conclude that 'low temperatures, short days and high relative humidity favor breeding in G. bengalensis, while rising temperatures and falling humidities are adverse.' Eggs are elliptical, white, sometimes with a few reddish brown marks, with a chalky surface (Fig. 1.1e). General dimensions are 87.9 x 69.7 and 84.4 x 66.4 mm (Wells 1999).

Different nesting locations have been recorded (Baral and Gautam 2007; Sharma 1970). Baral and Gautam state that trees are favored in the Rampur Valley, Nepal. This study located 42 nesting trees, comprising 33 kapok trees, 2 khair and 1 each of the other seven tree species (barro, kavro, ditabark, tuni, padke, saj and karma). The kapok (Ceiba pentandra Linnaeus) Gaertn. is a very large tree that grows 60-70 m (200-230 ft) tall with a butressed trunk of up to 3 m (10 ft) in diameter (Gibbs and Semir 2003). The barro (Terminalia chebula Retz.) is also a large deciduous tree growing up to 30 m (98 ft) tall, and a trunk up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) thick (Saleem et al. 2002). Similar species are the kavro (Ficus religiosa L.) (Singh et al. 2011), ditabark Alstonia scholaris L.R. Br. (World Conservation Monitoring Centre 1998), the saj (Terminalia alata Heyne ex Roth, or Terminalia tomentosa (Roxb.) Wight & Am.) and the karma (Adina cordifolia) (Willd. ex Roxb.) Benth. and Hook.f. ex Brandis. The khair (Senegalia catechu (L.f.) PJ.H. Hurter & Mabb) is slightly smaller, growing to about 15 m in height. The Padke, also known as the Persian Silk tree or the Pink Silk tree (Albizia julibrissin Durazz., 1772 non sensu Baker), 1876 is a smaller deciduous tree growing to only 5-12 m (Gilman and Watson 1993). Sharma's study (1970: 205) states that vultures use both cliffs and trees, cliffs being favored because they require fewer twigs and are a safer refuge from predators. For trees, favored species include the very large banyan tree (Ficus begalensis L.) and in more arid areas the large Prosopis spicigera L., this latter species described as the only 'tree that meets the vultures' nesting requirements.'

Population status. The distribution of the White-rumped vulture is shown in Fig. 1.1e. Recently, the White-rumped vulture was considered one of the commonest raptors worldwide, but its numbers have greatly declined (Gilbert et al. 2003, 2006; Green et al. 2004; Baral et al. 2005; Gautam et al. 2005; Arshad et al. 2009b; BirdLife International 2001, 2012; Cuthbert et al. 2011a,b; Chaudhary et al. 2012). This species was common in Myanmar in the nineteenth century, especially near the Gurkha cattle-breeding villages. Extensive populations were also recorded by Macdonald (1906), Hopwood (1912) and Stanford and Ticehurst (1935, 1938-1939).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 276;