Slender-billed Vulture (Gyps tenuirostris)

Physical appearance. The Slender-billed vulture is another medium-sized vulture. Compared to the other Gyps species, this species appears smaller-headed, larger-eyed, longer-billed, longer-legged, ragged, dingy, and graceless with a less feathered head and neck, and 'large prominent ear canals that are noticeable even at a distance, not like the smaller ones in the Indian vulture and other Gyps vultures' (Rasmussen et al. 2001: 25).

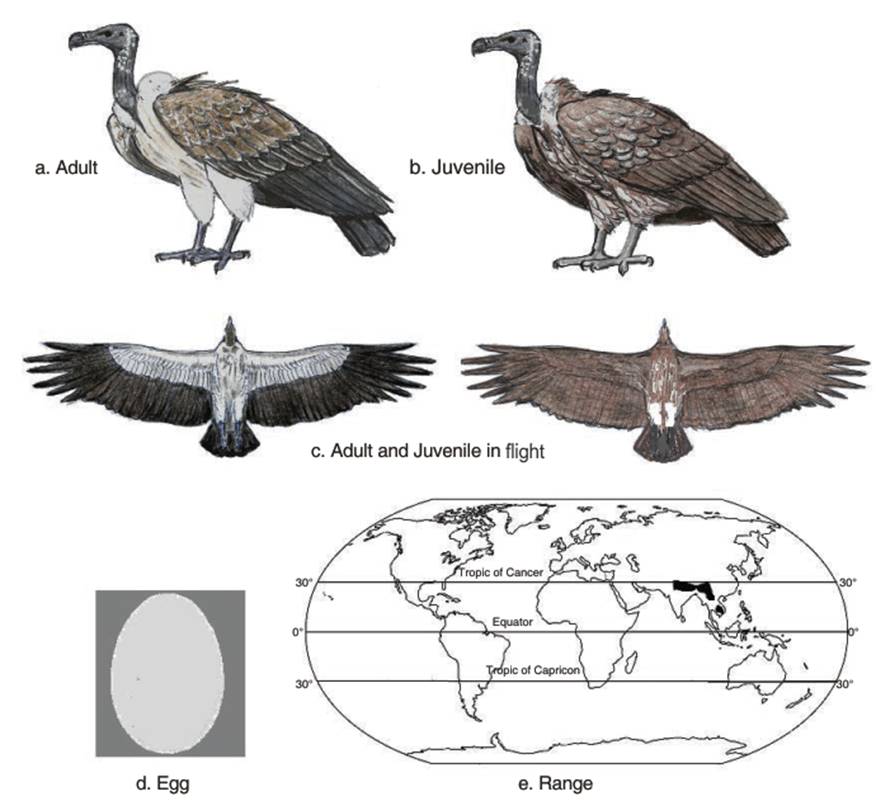

Seen from a perch, adults have a black, nearly featherless head and neck, a dark bill with a pale culmen and a black cere, and a dirty white ruff. Brown is the dominant feather color with lighter colored streaked underparts, and white thigh patches. Juveniles differ in having white down on the upper neck and nape, and streaked upperparts (BirdLife International 2014). Subadults are intermediate between adults and juveniles (Rasmussen et al. 2001) (Fig. 1.3a,b,c).

Fig. 1.3. Slender-billed Vulture

Classification. The Slender-billed vulture was formerly classified with the Indian vulture Gyps indicus as the Long Billed vulture Gyps indicus tenuirostris, but is now recognized as a different species (Rasmussen and Parry 2000). Arshad et al. (2009a) studied the phylogeny and phylogeography of the Gyps species, using nuclear (RAG-1) and mitochondrial (cytochrome b) genes, and concluded that G. indicus and G. tenuirostris are separate species. The Slender-billed vulture differs from the Indian vulture in having a slenderer bill and darker brown plumage (Hall et al. 2011). The two species are also found in different regions. The Slender-billed vulture, a tree nester, is found in Southeast Asia north to the Sub-Himalayan regions. The Indian vulture, mostly a cliff nester, is found south of the Ganges in India.

Foraging. The Slender-billed vulture shares similar habitat with the White-rumped vulture, i.e., open grassland, savanna or mixed dry forest with open patches, near or far from human habitation (Baker 1932-1935; Lekagul and Round 1991; Robson 2000; Satheesan 2000a,b; BirdLife International 2001). This is reflected in its diet, which comprises carcasses of domestic animals, and wild deer and pigs killed by tigers (Sarker and Sarker 1985). In Nepal, their main diet comprises domestic livestock rather than wild ungulates (Baral 2010).

Breeding. The breeding season is December-January, recorded in studies in India (Baker 1932-1935), Myanmar (Smythies 1986) and in Kamrup district, Assam (Saikia and Bhattacharjee 1990c). Only one egg is laid in regularly used nests (Brown and Amadon 1968), sometimes in groups of up to 16 birds (Baker 1932-1935) (Fig. 1.3d).

The Slender-billed vulture usually nests in large trees, such as the larger woody trees of the Genus Ficus, e.g., Ficus religiosa. This is a large deciduous or semi-evergreen tree up to 30 m (98 ft) tall, with a trunk diameter of up to 3 m (9.8 ft). Nests are located near or far from human settlement, usually 7 to 14 m (23-46 ft) high (Baker 1932-1935; Ali and Ripley 1968-1998; Brown and Amadon 1968; Grubh 1978; del Hoyo et al. 1994; Alstrom 1997; Grimmett et al. 1998; Rasmussen and Parry 2000). Nesting trees are the mango (Mangifera indica L.) and kadam (Anthocephalus indicus A. Rich.) in Kamrup district, Assam (Saikia and Bhattacharjee 1990). Other large trees were used for nesting in Myanmar (Smythies 1986) and in Khardah, Calcutta (Munn 1899, cited in BirdLife International 2001).

Population status. The distribution of the Slender-billed vulture is shown in Fig. 1.3e. It was one of the most numerous vultures in Southeast Asia during the first half of the twentieth century (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; Pain et al. 2003; Hla et al. 2010; Prakash et al. 2012). The population of this species, in combination with the Indian vulture, declined to 3.2% of its former level in 2007 in India (Prakash et al. 2007) with similar declines in Nepal (Chaudhary et al. 2012). Diclofenac, the anti-inflammatory drug for the treatment of livestock, contributed to renal failure, visceral gout and death in vultures (Oaks et al. 2004a; Shultz et al. 2004; Swan et al. 2005; Gilbert et al. 2006). The veterinary drug ketoprofen, was also toxic in concentrations (Naidoo et al. 2009). Processing of dead livestock also reduced vulture access to carcasses (Poharkar et al. 2009).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 186;