Ruppell's Vulture (Gypsrueppelli) (Alfred Brehm 1852)

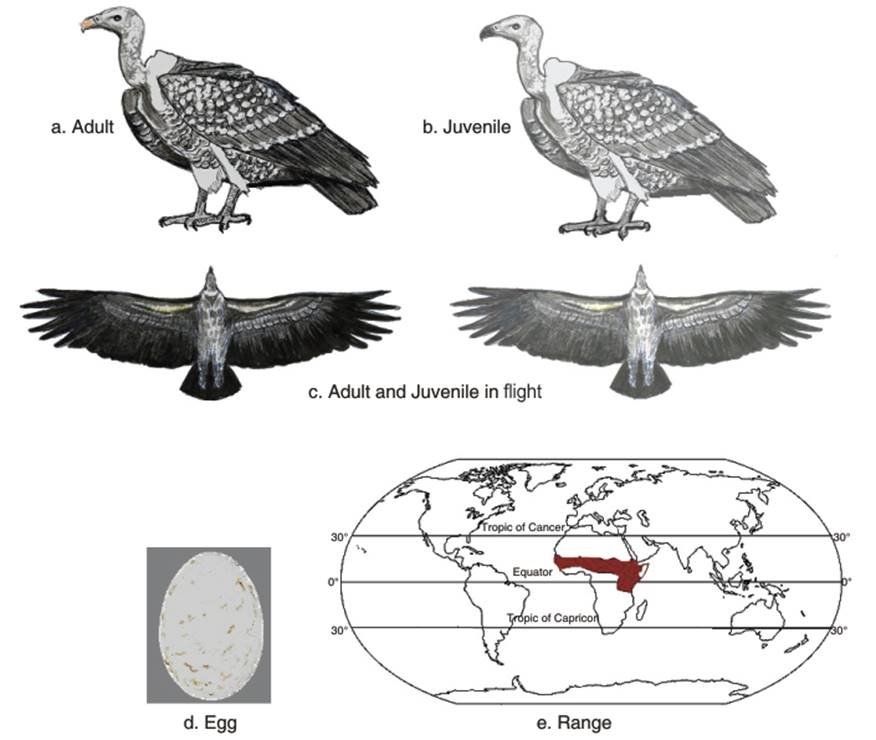

Physical appearance. The Ruppell's Griffon vulture, or the Ruppell's vulture, named after Eduard Ruppell, a nineteenth century German explorer, collector, and zoologist, is found mainly in the Sahel Savanna region of western and central Africa, between the Sudanian Savannas to the south and the Sahara Desert to the north (see Part 2, Chapter 6, 6.2. for a discussion of these terms). It is a large vulture, having a body length of 85 to 103 cm (33 to 41 in), a wingspan of 2.26 to 2.6 metres (7.4 to 8.5 ft), and a weight of 6.4 to 9 kg (14 to 20 lb) (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). It is similar to the White-backed vulture, Gyps bengalensis, but has a yellowish bill and is considerably larger. The head and neck are covered with white down feathers, and the base of the neck has a white collar. The plumage is mottled brown to dark brown or black with a mixed white-brown underbelly (Fig. 1.5a,b,c).

Fig. 1.5. Rüppell’s Griffon vulture

Classification. The Ruppell's Griffon vulture is closely related to the other species of the Genus Gyps. A study by Johnson et al. (2006: 65) using phylogenetic results from mitochondrial cytB, ND2 and control region sequence analysis 'supported a sister relationship between the Eurasian Vulture (G. f. fulvus), and Ruppell's Vulture (G. rueppellii), with this clade being sister to another consisting of the two taxa of "Long-billed" vulture (G. indicus indicus and G. i. tenuirostris), and the Cape Vulture (G. coprotheres)'.

Foraging. The foraging of this species is dependent on the large ungulate herds on the savannas. Migratory ungulates within the vultures' range, especially in East Africa include Blue Wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus, Burchell 1823) Burchell's Zebra (Equus burchelli Gray 1824) and Thomson's Gazelle (Eudorcas thomsonii, Gunther 1884) (Boone et al. 2006). A study by Kendall et al. (2012) found that the average number of Ruppell's vulture was higher during the ungulate migration season, enabling a fast response to wildlife density changes (Mundy et al. 1992; Kendall et al. 2012).

The Ruppell's Griffon is the commonest vulture of the Sahel savanna of Chad and Niger in West-Central Africa, Wacher et al. (2013). Here it feeds mostly on the carcasses of livestock (mostly camels, cattle, goats, horses and donkeys) rather than the outnumbered wild ungulates such as Dorcas Gazelle (Gazella dorcas, L. 1758), and to a lesser extent Dama Gazelle (Nanger dama, Pallas 1766) Barbary Sheep (Ammotragus lervia, Pall., 1777) and Addax (Addax nasomaculatus, de Blainville 1816). Ruppell's griffons in the Serengeti have been recorded as flying up to 150 km from the nest site to food source among the herds of migratory ungulates (Houston 1974b). Pennycuick (1972) suggested that the average foraging radius may be as far as 110 km.

The Ruppell's Griffon vulture is the world's highest-flying bird. An individual was involved in collision with an airplane over Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire, at 11,000 metres or 36,100 ft. This species has a specialized variant of the hemoglobin alphaD sub-unit which has a high affinity for oxygen which allows the species to absorb oxygen efficiently despite the low partial pressure in the upper troposphere (Laybourne 1974; Hiebl et al. 1988; Weber et al. 1988; Storz and Moriyama 2008).

Breeding. The breeding season of the Ruppell's Griffon varies greatly. For example, Virani et al. (2012) describe a colony in Kwenia, southern Kenya, composed of 150 to 200 adults (from 2002 and 2009) with a maximum of 64 nests occupied at any time. Egg laying dates varied each year; in some cases there were two egg-laying periods in one year (Fig. 1.5d). The number of nests was correlated with the previous year's rainfall. Ungulate populations in this area may have influenced breeding. The study concludes that nesting in Ruppell's vultures 'may be triggered' by rainfall and geared to producing fledged young at the end of the dry season (July-October) when carrion is most 'abundant' (ibid. 267). This point is also noted by Houston (1976). In another study, Houston (1990) found that the breeding time for colonies in the Serengeti region of Tanzania changed by 5 months between 1969-1970 and 1985, possibly correlated to the changes in ungulate populations. Food availability may have influenced two alternate breeding seasons, the choice of each period depending on the food available (Bouillault 1970; Mendelssohn and Marder 1989; Schlee 1988).

Nests may be in cliffs or rock outcrops or in trees. Tree nesting, considered atypical, has been recorded in West Africa (Rondeau et al. 2006). Wacher et al. (2013) give a detailed survey of Ruppell Griffon nesting and foraging presence in Chad and Niger in West-Central Africa (see also Scholte 1998). Of the 572 Ruppell's vultures recorded in the survey 47 nested on rocky inselbergs and 24 in tree crowns. Also, there were 24 cases of Ruppell's vultures using treetop stick nests, mostly on the crowns of the flat-topped thorny trees. Common tree species for nesting were the desert date (Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile 1812) a medium-sized tree and to a lesser extent jiga (Maerua crassifolia Forssk), a slightly smaller tree (Wacher et al. 2013).

Population status. The distribution of the Ruppell's Griffon vulture is shown in Fig. 1.5e. Ruppell's Griffon vulture is considered near threatened by conservationists. In West Africa there have been severe declines in Mali, South Sudan, Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Cameroon, Uganda, Kenya, Somalia and Malawi and may be extinct in Nigeria (Rondeau and Thiollay 2004; Thiollay 2001, 2006; Nikolaus 2006; Virani 2006; BirdLife International 2014).

One contributory factor may be the conversion of natural landcover to agriculture and urban landscapes (Buij et al. 2012). Other factors for the decline of the population of this species are poisoning from the toxic pesticide carbofuran, mostly in East Africa (Ogada and Keesing 2010; Otieno et al. 2010; Kendall and Virani 2012), the reduction of the ungulate wildlife populations (Western et al. 2009), diclofenac (BirdLife International 2007) and a substantial trade in vulture flesh and body parts, mostly in West Africa (Rondeau and Thiollay 2004; Nikolaus 2006). Possibly, there are also impacts from the actions of human climbing expeditions near the rocky outcrops in the Hombori and Dyounde massifs of Mali during the breeding season (Rondeau and Thiollay 2004).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 276;