Himalayan Griffon vulture (Gyps himalayans, Hume 1869)

Physical appearance. The Himalayan Griffon vulture or Himalayan vulture is a very large vulture, rivalling the Cinereous vulture as the largest of the Old World vultures (Mundy et al. 1992; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). The adult length is 109 to 115 cm (43-45 in). The weight may vary from 8 to 12 kg (18-26 lbs) and the wingspan varies from 2.6 to 3.1 m (8.5 to 10 ft) (Schlee 1989; Rasmussen and Anderton 2005; Namgail and Yoram Yom-Tov 2009). The Himalayan Griffon compared with the Cinereous vulture has a slightly longer body length due to the longer neck, but the largest of the latter species are larger and heavier than the largest Himalayan Griffons (Thiollay 1994; Grimmett et al. 1999; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; Chandler 2013).

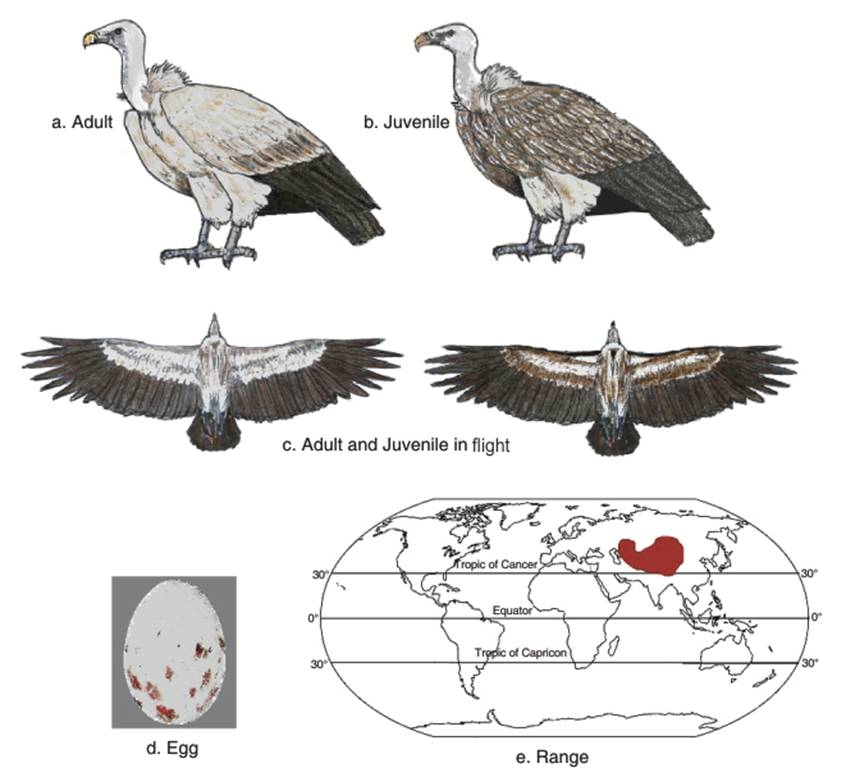

In coloration, adults have a pale brown, white streaked ruff, a yellowish- white down-covered head, pale brown to whitish underside, under-wing coverts and leg feathers, and white to grayish feet (Fig. 1.8 a,b,c). The upper body is pale buff, with no streaks, this color contrasting with the dark brown outer greater coverts and wing quills. The inner secondary feathers are paler on the tips. The facial skin is pale blue, a lighter color than the blue facial skin of Gyps fulvus. The bill is pale bluish-grey with darker tip, unlike the yellowish bill of Gyps fulvus. In flight it differs from Gyps fulvus in having dark wings and tail feathers that contrast with the pale body and coverts. It also differs from Gyps indicus in being larger with a larger bill. In juveniles, the down on the head is whiter, with whitish streaks on the scapulars and wing coverts, with dark brown underparts (Brown and Amadon 1986; Alstrom 1997; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; Rasmussen and Anderton 2005).

Fig. 1.8. Himalayan Griffon vulture

Classification. The Himalayan Griffon vulture is closely related to the European Griffon vulture (G. fulvus) and was considered a subspecies. In a study billed as the first inclusion of G. himalayensis and G. f. fulvescens in a molecular phylogenetic study, Johnson et al. (2006) found a close relation between G. himalayensis and G. f. fulvescens, in fact closer than the relation between G. f. fulvus and G. f. fulvescens, 'suggesting a topic for further analysis' (Johnson et al. 2006: 74).

Foraging. The Himalayan Griffon vulture forages in small groups over open meadows, alpine shrublands and open, partly forested landcover. The commonest food source are carcasses of domestic yak (64%), followed by human corpses (2%) and wild ungulates (1%) (Lu et al. 2009). Himalayan Griffon vultures are usually dominant over all other avian scavengers, except for the slightly larger Cinereous vulture (Thiollay 1994; Grimmett et al. 1999; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). This species forages widely; in fact there is evidence of its range spreading southwards into southeast Asia, possibly due to 'the decline of large mammals, leading to food shortage in the breeding range, and resulting in long-distance dispersal of the species', and also 'climate change, deforestation and hunting, coupled with natural patterns of post- fledging dispersal and navigational inexperience may be contributing to this change' (Li and Kasorndorkbua 2008: 57, 60).

Breeding. The Himalayan Griffon is one of the world's least-known vultures and opinions differ regarding their nesting (Flint et al. 1989). While some writers state that they are not colonial breeders, others state that they are semi-colonial breeders (Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). The Himalayan vulture is mostly a cliff nester, sometimes colonial, utilizing inaccessible ledges. Some nests in northeastern India were located between 1,215 and 1,820 m (3,986 and 5,970 ft) in altitude and in Tibet at 4,245 m (13,927 ft), with colonies of about 10 to 14 birds in pairs (Brown and Amadon 1989).

Nesting may be in association with other species, such as Bearded Vultures, with variable levels of conflict (Brown and Amadon 1989; Katzner et al. 2004b). The breeding season has been recorded as beginning in January, but variable dates have been recorded for egg-laying (for example in India from December 25 to March 7). The single white egg is marked with red irregular spots (Fig. 1.8d). In captivity, the general incubation period was about 54-58 days, and is similarly variable in the wild.

Population status. The distribution of the Himalayan Griffon vulture is shown in Fig. 1.8e. The main range of this species is in the higher altitudes of the Himalayas, the Pamirs, Kazakhstan and the Tibetan Plateau. In older sources, the breeding range was from Bhutan in the south to Afghanistan in the north (Peters 1931). However, as noted above, more recent literature sources have recorded young, vagrant and foraging birds in Southeast Asia, as far south as Thailand, Myanmar, Singapore and Cambodia (Li and Kasorndorkbua 2007).

The Himalayan Griffon vulture has not experienced the major population decline of the other Gyps vultures in Asia (Lu et al. 2009). The remote location of the Himalayan Plateau and protection by Tibetan Buddhism are possible factors for this. The total population in the Tibetan Plateau is estimated at 229,339 (+/-40,447). The maximum carrying capacity of the plateau, based on food possibilities, may be 507,996 Griffons. The main habitat would be meadow habitats, which would support 76% of this population (Lu et al. 2009).

Although similar to the other Gyps species, the Himalayan Griffon vulture is recorded as less susceptible to the effects of diclofenac. There is no evidence of strong decline in their numbers over their range, despite population reductions in Nepal (Virani et al. 2008; Acharya et al. 2009). This may partly be the result of their remote range and individuals dispersing into the lowlands of southeast Asia might be more vulnerable (Li and Kasorndorkbua 2008).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 325;