Cinereous Vulture, Aegypius monachus (Linnaeus 1766)

Physical appearance. The Cinereous vulture, has also been called the Black vulture or the Eurasian Black vulture, due to its all dark appearance. These latter names are still frequently used in publications in Europe, but there is confusion with the unrelated and smaller American Black vulture (Coragyps atratus). It has also been called the Monk vulture; this is a translation of the German name Monchsgeier, which refers to the similarity between the vulture's bald head, feathered neck ruff and dark plumage and the cowl and clothing of a monk (Sibley and Monroe 1991). The name Cinereous is Latin for cineraceus, which means grey or ash-colored, and allows it to be distinguished from the American Black Vulture (Sibley and Monroe 1991).

This is a huge vulture, generally considered the largest Old World vulture, the largest member of the Family Accipitridae (and sometimes also the Order Falconiformes, if the slightly larger New World Condors are excluded) and therefore one of the world's largest flying birds (Sibley and Monroe 1991; Del Hoyo et al. 1994; Snow and Perrins 1998; BirdLife International 2014). Apart from the condors, its main rival in size is the Himalayan Griffon vulture; however the largest Cinereous vultures are recorded as exceeding the wingspan and weight of the largest Himalayan Griffon vultures, even if the long neck of the Griffon vulture gives it a slightly greater length (Brown and Amadon 1986; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). The Cinereous vulture may be 98-120 cm (3 ft 3 in-3 ft 11 in) long from bill to tail, with females weighing 7.5 to 14 kg (17 to 31 lb), and the smaller males 6.3 to 11.5 kg (14 to 25 lb). The wingspan is about 2.5-3.1 m (8 ft 2 in-10 ft 2 in). Ferguson-Lees and Christie (2001) describe a cline of increased body size from west to east, as the birds from central Asia (Manchuria and Mongolia, southwards into northern China) are generally about 10% larger than those from southwest Europe (mostly Spain and southern France).

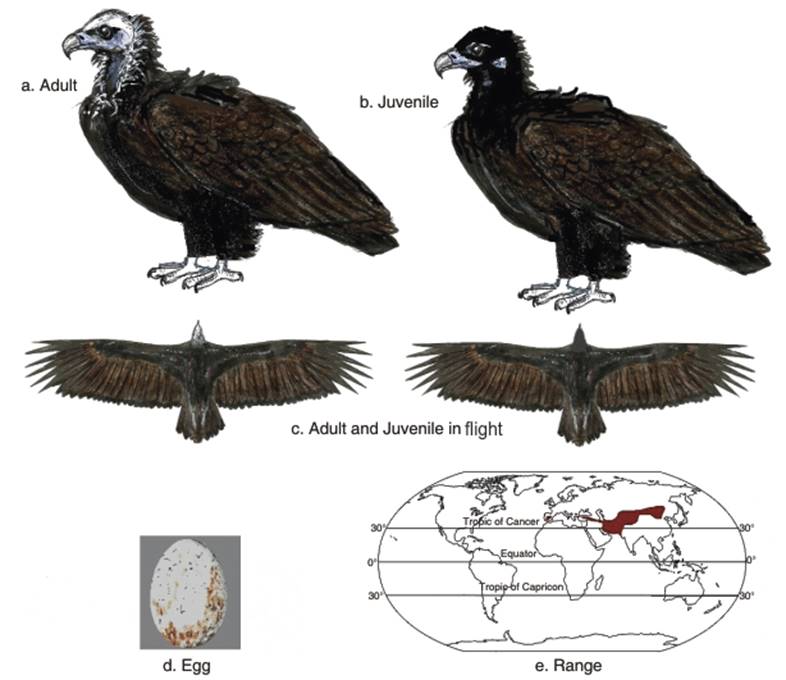

The bare skin of the head and neck is bluish grey and the head is covered with blackish down. The black to blue-grey bill is massive, similar to those of the other very large vultures (the Lappet-faced vulture, Bearded vulture and Himalayan Griffon vulture) (Fig. 2.8 a,b,c). The legs are pale blue-grey. The adult plumage is all dark brown to blackish brown, with a short, slightly wedge-shaped tail. The juvenile plumage is brown above, and paler underside than in adults, with grey rather than blue-grey legs (Brown and Amadon 1986; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). This dark bird may be distinguished from the other large vulture in the southern Middle East, the Lappet-faced vulture, as the latter bird has reddish to pinkish skin on the head and whitish feathers on the thighs and belly. The Gyps vultures are distinguished from the dark Cinereous vulture by their paler plumage and longer, down-covered necks.

Fig. 2.8. Cinereous Vulture

Classification. The Cinereous vulture, as noted in the description of the Genera Gyps, Sacrogyps, Torgos, and Trigonoceps, is classified by the nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene as belonging to Aegypiinae, the larger of the two clades of Old World vultures (Wink 1995; Stresemann and Amadon 1979; Amadon and Bull 1988; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). According to Wink (1995), the Cinereous vulture and the Lappetfaced vulture (Torgos tracheliotus) are sister species, which differ by 3.8% nucleotide substitutions.

Foraging. The Cinereous vulture forages in forests, and more open terrain such as steppe and upland grasslands (Heredia 1996). Flint et al. 1984 write that favored landcover includes arid hilly and montane habitat, with both semidesert and wooded areas, mountainous areas above the treeline, and mixed agricultural and forested patches. Hiraldo and Donazar (1990: 131) note that the 'the foraging areas the Cinereous vultures use are preferentially plains and hills of gentle relief' (see also Hiraldo 1976; Amores 1979). In China it is observed in prairies and open farmlands (Weizhi 2006). In Israel, it is recorded from mountains, plateaus, desert wadis, and also grazed highlands and plains (Shirihai 1996). In Armenia, the favored habitat appears to be eroded cliffs with cavities and mountainous slopes with clay-gypsum, gravel and/or scree (Adamian and Klem 1999). In Kazakhstan it is recorded in semi-deserts, deserts and low mountains (Wassink and Oreel 2007). Juveniles, especially from the northern ranges move across large distances in open-dry habitats due to snowfall or hot summer temperature in local areas (Brown and Amadon 1986; Gavashelishvili et al. 2012).

In feeding at carcasses, the Cinereous vulture is dominant over other large vultures such as the Gyps and Bearded vultures and also over smaller mammals such as foxes (Brown and Amadon 1986). It is well equipped to tear open thick skins and ribs (Gavashelishvili et al. 2006). Moreno-Opo et al. (2010: 25) studied the eating preferences of the Cinereous vulture in Spain and found that 'the number of cinereous vultures that come to feed on the carcasses is related to the quantity of biomass present and to the types of pieces of the provided food.' They prefer 'individual, mediumsized muscular pieces and small peripheral scraps of meat and tendon.' Therefore, the time before the vultures began consumption depended on the 'biomass delivered, the number of pieces into which it is divided, and the type categories of the provided food.'

The carrion diet of the Cinereous vulture varies according to the region. For example, in Western Europe, carcasses consumed are usually those of smaller mammals, as there are fewer large non-domesticated mammals in this region than in Turkey and Asia. In the Iberian Peninsula the common food source was the European Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus, Linnaeus 1758), but the decline of the rabbit numbers, due to the disease viral hemorrhagic pneumonia (VHP) contributed to vultures feeding on dead domestic sheep (Ovis aries, Linnaeus 1758), supplemented by pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus Erxleben 1777), red deer (Cervus elaphus, Linnaeus 1758) and fallow deer (Dama dama, Linnaeus 1758) (Gonzalez 1994; Costillo et al. 2007a). In Turkey, the larger animals eaten included Argali (Ovis ammon, Linnaeus 1758), Wild Boar (Sus scrofa, Linnaeus 1758) and Gray Wolf (Canis lupus, Linnaeus 1758). Smaller animals eaten were the Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes, Linnaeus 1758) and domestic chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus, Linnaeus 1758); in some cases there was evidence of the ingestion of pine cones (Yamag and Gunyel 2010).

In Tibet, there are records of vultures eating the carcasses of wild and domestic Yaks (Bos grunniens, Linnaeus 1766), Bharal or Himalayan blue sheep (Pseudois nayaur, Hodgson 1833), Kiangs (Equus kiang Moorcroft, 1841), Woolly Hares (Lepus oiostolus Hodgson 1840), Himalayan Marmots (Marmota himalayana Hodgson 1841) and domestic sheep (Ovis aries, Linnaeus 1758) (Xiao-Ti 1991). In Mongolia, their main food was Tarbagan Marmots (Marmota sibirica, Radde 1862); also eaten were Argali (Ovis ammon, Linnaeus 1758) (Del Hoyo et al. 1994).

Living prey was also taken in China; these included 'calves of yak and cattle, domestic lambs and puppies, pig, fox, lambs of wild sheep, together with large birds such as goose, swan and pheasant, various rodents and rarely amphibia and reptiles' (Xiao-Ti 1991). Other Asian ungulates taken include neonatal or sickly lambs or calves, and also healthy lambs (Richford 1976). Other mammals killed are Argali, Saiga Antelope (Saiga tatarica, Linnaeus 1766), Mongolian gazelle (Procapra gutturosa, Pallas 1777) and Tibetan Antelope (Pantholops hodgsonii, Abel 1826) (Olson et al. 2005; Buuveibaata et al. 2012).

Breeding. Breeding areas also vary according to the region; however the main classification is of large nests in large trees and occasionally rocky cliffs and mountain faces with crevices and cavities (Brown and Amadon 1986; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; Kirazli and Yamag 2013). Rock nesting is rare in Europe but more common in Asia (Batbayar et al. 2006; BirdLife International 2014). Breeding in Europe requires quiet slopes with forests, including low sierras and open valleys, sometimes also subalpine forests of Pinus spp. up to an altitude of 2,000 m and open parkland (Heredia 1996). In Spain, common habitats are forested hills and mountains 300-1,400 m high. In Asia, it inhabits higher altitudes up to 4,500 m, including scrub and arid and semi-arid alpine steppe and grasslands (Thiollay 1994). Xiao-Ti (1991) reports that 'the breeding habitat of the Cinereous vulture in China falls into two main types: mountainous forest and scrub between 780 m and 3800 m; and arid and semi-arid Alpine meadow and grassland, between 3800 m and 4500 m'.

In China, various authors have described the breeding habitats of Cinereous vultures (Xiao Ti 1991). For example, Futong Sheng et al. (1984) write that the favored habitat is mixed forest above 800 m in the Changbai mountains. For Cheng Tso-Hsin et al. (1963) the preferred habitat was above 2000 m at Xinjiang in the Altay mountains. Also noted were rocky, grass-covered mountain areas above 2000 in Sichuan (Li Gei Yan et al. 1985); regions of alpine meadow and scrub about 3000 m altitude in northwest Sichuan (Cheng Tso-Hsin 1965); above 1000 m in secondary mixed forest and scrub on the loess plateau of northern Shangxi (Yao Jianchu 1985); between 500 m and 3200 m in areas of mixed forest/scrub and farmland in South Shangxi (Cheng Gangmei 1976) and between 780 and 3400 m and mixed conifer and broadleaf forest (Betula spp.), with Alpine meadowland and scrub on the slopes of the Qinling Mountains (Cheng Tso-Hsin 1973).

Also recorded for China were semi-arid regions with coniferous forest, scrub and meadowland in Ningxia (Wang Xian Tin et al. 1977); 770 m altitude in an area of swamp, river, lake and desert around Lop Lake in Xinjiang (Gao Xingni et al. 1985); around 1000 m altitude in desert areas of South Xinjiang (Qian Yan Wen et al. 1965); between 1000 m and 4000 m in semi-arid, arid and mountainous regions of coniferous forest, Alpine scrub and pasture in Gansu (Wang Xiantin 1981); and between 3000 m and 4500 m in coniferous forest, Alpine scrub and pasture or semi-arid grassland in Qinghai (Ye Xiao Ti et al. 1988, 1989). Xiao Ti (1991) summarizes the different reports, noting that these fall into two different types; mountainous forest and scrub between 780 m and 3800 m, and arid and semi-arid Alpine meadow and grassland, between 3800 m and 4500 m altitude.

The Cinereous vulture usually breeds either in solitary nests or in loose colonies (Kirazli and Yamag 2013). The nests are usually situated in trees 1.5 to 12 m high (4.9 to 39.4 ft), often along cliffs. Common trees utilized for nesting are oak (Quercus L. spp.), juniper (Juniperus L. spp.), almond (Prunus dulcis (Mill.)) D.A. Webbor and pine trees (Pinus L.) (Brown and Amadon 1986). Birds start breeding at about 5-6 years. One white or pale buff egg with red to brown marks is laid (Fig. 2.8d). The egg laying period is usually from the beginning of February to the end of April, clustering from the end of February and to the beginning of March. Incubation lasts 50-54 days, and fledging more than 100 days (Hiraldo 1983, 1996; Reading et al. 2005; Gavashelishvili et al. 2012).

Population status. The distribution of the Cinereous vulture is shown in Fig. 2.8e. Several threats have reduced the population of the Cinereous vulture (Heredia 1996). Most of the declines in the past decades have occurred in the western part of the birds' range (i.e., France, Italy, Austria, Poland, Slovakia, Albania, Moldovia, Romania, and Morocco and Algeria) (del Hoyo et al. 1994; Snow and Perrins 1998; Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001; Gavashelishvili et al. 2006).

Forestry disturbs breeding and removes trees used for nesting. Forest fires develop during the dry season and destroy nests and trees, especially in the Mediterranean region. For example, a fire in 1992 in Andalucia burned down eight nests with young birds, and 21 empty nests (Andalus 1993). Cinereous vultures are regularly killed after ingesting meat from carcasses laced with poisons (including strychnine and luminal) and pesticides in contravention of the Berne Convention. Recent measures have also reduced livetsock numbers in the field, removed carcasses and accommodated cattle and sheep indoors during winter. A few vultures are also shot for sport. Vultures are captured illegally for zoos in the post-USSR countries. Trapping and hunting of Cinereous Vultures is particularly common in China and Russia (del Hoyo et al. 1994). Mountain tourism, also disturbs nesting vultures especially in the Caucasus. Records show that human disturbance during incubation can result in egg losses due to crow predation (Heredia 1996).

Cinereous vulture populations nevetheless increased by over 30 percent between 1990 and 2000 (BirdLife International 2014). Overall, there are reported to be 7,200-10,000 pairs, of which 1,700-1,900 pairs are in Europe and 5,500-8,000 in Asia (BirdLife International 2004). In Europe, populations are reportedly increasing in Spain (probably 1,500 pairs) Portugal and France, and are stable in Greece and Macedonia, but they are decreasing in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Russia, Turkey and the Ukraine (De la Puente et al. 2007; Eliotout et al. 2007; BirdLife International 2014). Asian birds are less studied, despite reported declines in populations (Baral 2005; Batbayar 2005; Fremuth 2005; Katzner 2005; Batbayar et al. 2006; Lee et al. 2006; Barov and Derhe 2011; BirdLife International 2014).

Date added: 2025-04-29; views: 183;